The historic 1964 Civil Rights Act became law 59 years ago today

President Lyndon Johnson shakes hands with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. after signing the 1964 Civil Rights Act

On this day in 1964 — 59 years ago — President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the historic Civil Rights Act in a nationally televised ceremony at the White House.

In the landmark 1954 case, Brown v. Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in schools was unconstitutional. The ten years that followed saw great strides for the African-American civil rights movement — as non-violent demonstrations won thousands of supporters to the cause.

Memorable landmarks in the struggle included the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 — sparked by the refusal of Alabama resident, Rosa Parks, to give up her seat on a city bus to a white woman — and Martin Luther King, Jr.'s famous "I have a dream" speech at a rally of hundreds of thousands in Washington, D.C., in 1963.

As the strength of the civil rights movement grew, John F. Kennedy made passage of a new civil rights bill one of the platforms of his successful 1960 presidential campaign. As Kennedy's vice president, Johnson served as chairman of the President's Committee on Equal Employment Opportunities.

After Kennedy was assassinated in November, 1963, Johnson vowed to carry out his proposals for civil rights reform. The Civil Rights Act fought tough opposition in the House and a lengthy, heated debate in the Senate before being approved in July, 1964.

For the signing of the historic legislation, Johnson invited hundreds of guests to a televised ceremony in the White House's East Room. After using more than 75 pens to sign the bill, he gave them away as mementoes of the historic occasion, according to tradition.

One of the first pens went to King, leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), who called it one of his most cherished possessions. Johnson gave two more to Senators Hubert Humphrey and Everett McKinley Dirksen, the Democratic and Republican managers of the bill in the Senate.

The most sweeping civil rights legislation passed by Congress since the post-Civil War Reconstruction era, the Civil Rights Act prohibited racial discrimination in employment and education and outlawed racial segregation in public places such as schools, buses, parks and swimming pools.

In addition, the bill laid important groundwork for a number of other pieces of legislation — including the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which set strict rules for protecting the right of African Americans to vote — that have since been used to enforce equal rights for women as well as all minorities.

Sadly, the legislation would probably have never passed without the assassination of Kennedy in 1963.

Ramsey Clark, the later Attorney General who worked during the Kennedy Administration for Robert F. Kennedy, told me in an interview that the legislation was so unpopular when Kennedy was alive it never could have passed on his watch.

It was after Kennedy was shot in Dallas, Clark said, that Johnson was able to push through the legislation as a tribute to the slain leader.

Thanks History.com

On July 2, 1937 — 86 years ago today — the Lockheed aircraft carrying American aviator, Amelia Earhart, and navigator, Frederick Noonan, was reported missing near Howland Island in the Pacific.

The pair were attempting to fly around the world when they lost their bearings during the most challenging leg of the global journey: Lae, New Guinea, to Howland Island — a tiny island 2,227 nautical miles away in the center of the Pacific Ocean.

The U.S. Coast Guard cutter, Itasca, was in sporadic radio contact with Earhart as she approached Howland Island and received messages that she was lost and running low on fuel. Soon after, she probably tried to ditch the Lockheed in the ocean. No trace of Earhart or Noonan was ever found.

Born in Atchison, Kansas, in 1897, Amelia Earhart took up aviation at the age of 24 and later gained publicity as one of the earliest female aviators. In 1928, the publisher, George P. Putnam, invited her to become the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean.

The previous year, Charles A. Lindbergh had flown solo nonstop across the Atlantic, and Putnam had made a fortune off Lindbergh's autobiographical book, We. In June, 1928, Earhart and two men flew from Newfoundland, Canada, to Wales, Great Britain. Although Earhart's only function during the crossing was to keep the plane's log, the flight won her great fame.

Americans were enamored of the daring young pilot. The three were honored with a ticker-tape parade in New York, and "Lady Lindy," as Earhart was dubbed, was given a White House reception by President Calvin Coolidge. Earhart wrote a book about the flight for Putnam, whom she married in 1931, and gave lectures and continued her flying career under her maiden name.

On May 20, 1932, she took off alone from Newfoundland in a Lockheed Vega on the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight by a woman. She was bound for Paris, but was blown off course and landed in Ireland on May 21 after flying more than 2,000 miles in just under 15 hours. It was the fifth anniversary of Lindbergh's historic flight, and before Earhart, no one had attempted to repeat his solo transatlantic flight.

For her achievement, she was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by Congress. Three months later, Earhart became the first woman to fly solo nonstop across the continental United States.

In 1935, in the first flight of its kind, she flew solo from Wheeler Field in Honolulu to Oakland, California, winning a $10,000 award posted by Hawaiian commercial interests. Later that year, she was appointed a consultant in careers for women at Purdue University, and the school bought her a modern Lockheed Electra aircraft to be used as a "flying laboratory."

On March 17, 1937, she took off from Oakland and flew west on an around-the-world attempt. It would not be the first global flight, but it would be the longest — 29,000 miles, following an equatorial route. Aboard her Lockheed were Frederick Noonan, her navigator and a former Pan American pilot, and co-pilot, Harry Manning.

After resting and refueling in Honolulu, the trio prepared to resume the flight. However, while taking off for Howland Island, Earhart ground-looped the plane on the runway, perhaps because of a blown tire, and the Lockheed was seriously damaged. The flight was called off, and the aircraft was shipped back to California for repairs.

In May, Earhart flew the newly rebuilt plane to Miami, from where Noonan and she would make a new around-the-world attempt, this time from west to east. They left Miami on June 1, and after stops in South America, Africa, India and Southeast Asia, they arrived at Lae, New Guinea, on June 29. About 22,000 miles of the journey had been completed.

The last 7,000 miles would all be over the Pacific Ocean. The next destination was Howland Island, a tiny U.S.-owned island that was just a few miles long. The U.S. Department of Commerce had a weather observation station and a landing strip on the island and the staff was ready with fuel and supplies. Several U.S. ships, including the Coast Guard cutter, Itasca, were deployed to aid Earhart and Noonan in this difficult leg of their journey.

As the Lockheed approached Howland Island, Earhart radioed the Itasca and explained that she was low on fuel. However, after several hours of frustrating attempts, two-way communication was only briefly established. The Itasca was unable to pinpoint the Lockheed's location or offer navigational information.

Earhart circled the Itasca's position, but was unable to sight the ship, which was sending out miles of black smoke. She radioed "one-half hour fuel and no landfall" and later tried to give information on her position. Soon after, contact was lost. Earhart presumably tried to land the Lockheed on the water.

If her landing on the water was perfect, Earhart and Noonan might have had time to escape the aircraft with a life raft and survival equipment before it sank. An intensive search of the vicinity by the Coast Guard and U.S. Navy found no physical evidence of the fliers or their plane.

Additional searches through the years have likewise failed to find any trace of the Lockheed or of Earhart and Noonan, who almost certainly perished at sea. After decades of searches, researchers found a part of the wreckage from Earhart’s plane near Hawaii and it has been confirmed as authentic. It is now regarded as a control piece that will help to authenticate possible future discoveries.

Thanks History.com

Earl Robinson and Paul Robeson working on Ballad for Americans, 1939

Earl Robinson was born 112 years ago today.

A singer-songwriter and composer from Seattle, Robinson wrote such songs as "Joe Hill," "Black and White" and the cantata, "Ballad for Americans." In addition, he wrote many popular songs and was a composer for Hollywood films.

Robinson studied violin, viola and piano as a child, and studied composition at the University of Washington, receiving a music degree and teaching certificate in 1933. In 1934, he moved to New York City, where he studied with Hanns Eisler and Aaron Copland.

He was also involved with the depression-era WPA Federal Theater Project, and was actively involved in the anti-fascist movement. He was the musical director at the Communist-run, Camp Unity, in upstate New York.

In the 1940s, he worked on film scores in Hollywood until he was blacklisted for being a Communist. Unable to work in Hollywood, he moved back to New York, where he headed the music program at Elisabeth Irwin High School, directing the orchestra and chorus.

Robinson's musical influences included Paul Robeson, Lead Belly and American folk music. He composed "Ballad for Americans" (lyrics by John La Touche), which became a signature song for Robeson. It was also recorded by Bing Crosby. He wrote the music for and sang in the short documentary film, Muscle Beach (1948), directed by Joseph Strick and Irving Lerner.

Other songs written by Robinson include "The House I Live In" (a 1945 hit recorded by Frank Sinatra) and "Joe Hill," a setting of a poem by Alfred Hayes. “Joe Hill” was later recorded by Joan Baez and used in the film of the same name. He also wrote the ongoing ballad that accompanied the film, A Walk in the Sun, that was sung by Kenneth Spencer.

Robinson wrote, “Lonesome Train,” a musical poem on the life and death of Abraham Lincoln.

He wrote "Black and White" with David I. Arkin, the late father of actor Alan Arkin. It was a celebration of the Brown v. Board of Education decision. The song was recorded by Pete Seeger, Three Dog Night, the Jamaican reggae band, The Maytones, Sammy Davis, Jr. and Greyhound, the UK reggae band.

His late works included a concerto for banjo, as well as a piano concerto entitled, The New Human. His cantata based on the preamble to the constitution of the United Nations was premiered in New York with the Elisabeth Irwin High School Chorus and the Greenwich Village Orchestra in 1962 or 1963.

Robinson was killed at the age of 81 in a car accident in his hometown of Seattle in 1991. The jazz clarinetist Perry Robinson is his son.

Here, several artists, including Joan Baez, Pete Seeger and Three Dog Night, perform a medley of songs written by Earl Robinson in a trailer for Earl Robinson: Ballad of an American.

One of the Surrounded Islands, taken from a helicopter, May, 1983 — 40 years ago

Photo by Frank Beacham

The artist couple of Christo and Jeanne-Claude did a project based on Jeanne-Claude's idea to surround eleven islands in Miami's Biscayne Bay with pink polypropylene floating fabric.

It was completed on May 4, 1983, with the aid of 430 workers and was left standing for two weeks.

Surrounded Islands was located between the city of Miami, North Miami, the Village of Miami Shores and Miami Beach, 11 of the islands situated in the area of Bakers Haulover Cut, Broad Causeway, 79th Street Causeway, Julia Tuttle Causeway and Venetian Causeway.

The islands were surrounded with 6.5 million square feet of pink woven polypropylene fabric covering the surface of the water, floating and extending out 200 feet from each island into the Bay.

The fabric was sewn into 79 patterns to follow the contours of the 11 islands.

For two weeks Surrounded Islands, spreading over seven miles, was seen, approached and enjoyed by the public, from the causeways, the land, the water, and the air.

The luminous pink color of the shiny fabric was in harmony with the tropical vegetation of the uninhabited verdant island, the light of the Miami sky, and the colors of the shallow waters of Biscayne Bay.

As with Christo and Jeanne-Claude's previous art projects, Surrounded Islands was entirely financed by the artists through the sale by C.V.J. Corporation (Jeanne-Claude Christo-Javacheff, President) of the preparatory pastel and charcoal drawings, collages, lithographs and early works.

Christo died in 2020; Jean-Calude in 2009.

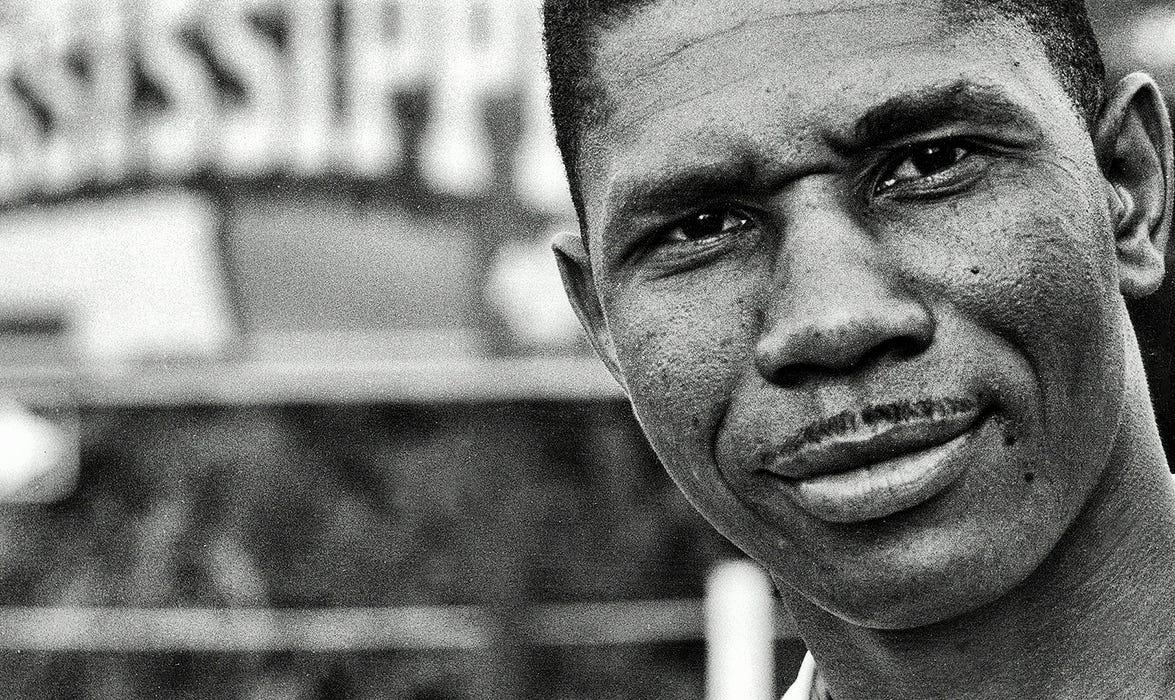

Medgar Evers was born 98 years ago today.

The African American civil rights activist was involved in efforts to overturn segregation at the University of Mississippi. He was active in the civil rights movement after returning from overseas service in World War II and became a field secretary for the NAACP.

Evers was assassinated by Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the Mississippi White Citizens' Council, on June 12, 1963. As a veteran, Evers was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Evers’ death inspired civil rights protests, as well as numerous works of art, music and film. His murder and subsequent trials caused an uproar.

Bob Dylan wrote his 1963 song, "Only a Pawn in Their Game," about Evers and his assassin. Nina Simone wrote and sang, "Mississippi Goddam." Phil Ochs wrote the songs, "Too Many Martyrs" and "Another Country," in response to the killing.

Matthew Jones and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Freedom Singers paid tribute to Evers in the haunting, "Ballad of Medgar Evers."

Eudora Welty's short story, "Where Is the Voice Coming From," in which the speaker is the imagined assassin of Medgar Evers, was published in The New Yorker. Rex Stout used the event as a plot device in his civil rights-themed mystery, A Right to Die.

On July 5, 1963, Bob Dylan flew through the night to perform “Only a Pawn in Their Game” at a civil rights, voter registration rally in Greenwood, Mississippi.

Gregory Peck with Brock Peters in To Kill a Mockingbird, 1962

Brock Peters was born 96 years ago today.

Peters played the role of Tom Robinson in the 1962 film, To Kill a Mockingbird.

Born George Fisher in New York City, Peters was the son of Alma A. and Sonnie Fisher, a sailor. At only 10, Peters set his sights on a show business career. A product of New York's High School of Music and Art, Peters initially fielded more odd jobs than acting jobs as he worked his way up from Harlem poverty.

Landing a stage role in Porgy and Bess in 1949, Peters quit physical education studies at City College of New York and went on tour with the opera. He made his film debut in Carmen Jones in 1954, but began to make a name for himself in such films as To Kill a Mockingbird and The L-Shaped Room. He received a Tony nomination for his starring stint in Broadway's, Lost in the Stars.

Peters sang background vocals on the 1956 hit, "The Banana Boat Song (Day-O)" by Harry Belafonte, as well as on Belafonte's 1957 hit, "Mama Look a Boo-Boo." In the film, Abe Lincoln, Freedom Fighter (1978), Peters plays Henry, a freed black slave who is falsely accused of robbery. But, defended by Abraham Lincoln, is found not guilty due to the fact he has a damaged hand and could not have committed the crime.

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Peters plays Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused of raping a white girl, whom Atticus Finch shows could not have committed because his hand (and arm) were damaged. Peters read Gregory Peck's eulogy at Peck's funeral in 2003. Brock's character, Tom Robinson, was defended by Peck's Atticus Finch in the film.

He died in Los Angeles of pancreatic cancer on August 23, 2005 at the age of 78.

Here, Peters in a scene from 1962’s “To Kill a Mockingbird”

Paul Williams (left front) and the Temptations

Paul Williams, founding member of the Temptations, was born 84 years ago today.

A baritone singer and choreographer, Williams along with David Ruffin, Otis Williams (no relation) and fellow Alabamians, Eddie Kendricks and Melvin Franklin, founded the legendary Motown group. Williams was a member of The Temptations during the "Classic Five" period.

Personal problems and failing health forced Williams to retire in 1971. He was found dead two years later as the result of an apparent suicide.

Born and raised in the Ensley neighborhood of Birmingham, Alabama, Williams was the third son of Sophia and Rufus Williams, a gospel singer in the Ensley Jubilee Singers.

He met his lifelong best friend, Eddie Kendricks, in elementary school. The two first encountered each other in a fistfight after Williams dumped a bucket of mop water on Kendricks. The two eventually became good friends. Both boys shared a love of singing and sang in their church choir together.

As teenagers, Williams, Kendricks and their friends, Kel Osbourne and Willie Waller, performed in a secular singing group known as The Cavaliers. They had dreams of making it big in the music business.

In 1957, Williams, Kendricks and Osbourne left Birmingham to start careers, leaving Waller behind. Now known as The Primes, the trio moved to Cleveland, and eventually found a manager in Milton Jenkins, who moved the group to Detroit.

Although The Primes never recorded, they were successful performers, and even launched a spin-off female group. They were called The Primettes, who later became, The Supremes.

In 1961, Kell Osbourne moved to California, and the Primes disbanded. Kendricks returned to Alabama, but visited Paul in Detroit shortly after. While on this visit, he and Paul had learned that Otis Williams, head of a rival Detroit act known as The Distants, had two openings in his group's lineup.

Paul Williams and Kendricks joined Otis Williams, Melvin Franklin and Elbridge Bryant to form The Elgins, who signed to the local Motown label in 1961 after first changing their name to The Temptations.

Although the group now had a record deal, Paul Williams and his bandmates endured a long series of failed singles before finally hitting the Billboard Top 20 in 1964 with "The Way You Do the Things You Do." More hits quickly followed, including "My Girl," "Ain't Too Proud To Beg" and "(I Know) I'm Losing You."

Williams suffered from sickle-cell anemia, which frequently wreaked havoc on his physical health. Life on the road was starting to take its toll on Williams as well, and he began to drink heavily.

In 1969, after a failed business and being in debt, his health had deteriorated to the point that he would sometimes be unable to perform, suffering from combinations of exhaustion and pain which he combated with heavy drinking.

Each of the other four Temptations did what they could to help Williams, alternating between raiding and draining his alcohol stashes, personal interventions and keeping oxygen tanks backstage. But Williams' health, as well as the quality of his performances, continued to decline and he refused to see a doctor.

In April, 1971, Williams was finally persuaded to go see a doctor. The doctor found a spot on Williams' liver and advised him to retire. Williams left the group. On August 17, 1973, Williams was found dead in an alley, in the car with a gun, having just left the new house of his then-girlfriend after an argument. A gun was found near his body.

His death was ruled a suicide by the coroner. Williams had expressed suicidal thoughts to Otis Williams and Melvin Franklin months before his death.

Here, Paul Williams and the Temptations perform “For Once In My Life”

Hermann Hesse was born 146 years ago today.

Hesse was a German-born Swiss poet, novelist and painter. His works include Steppenwolf, Siddhartha and The Glass Bead Game. Each work explores an individual's search for authenticity, self-knowledge and spirituality.

In 1946, Hesse received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Secretary, circa 1950