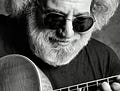

The Grateful Dead's Jerry Garcia died 28 years ago today

Jerry Garcia

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

Like his band the Grateful Dead, which was still going strong three decades after its formation, Jerry Garcia defied his life-expectancy not merely by surviving, but by thriving creatively and commercially into the 1990s — far longer than most of his peers.

His long, strange trip came to an end, however, on this day in 1995 — 28 years ago — when he died of a heart attack in a residential drug-treatment facility in Forest Knolls, California.

A legendary guitarist and true cultural icon, Jerry Garcia was 53 years old.

Garcia was born on August 1, 1942 and raised primarily in San Francisco's Excelsior District, about five miles south of his and his band's famous future residence at 710 Ashbury Street. Trained formally on the piano as a child, Garcia picked up the instrument he'd make his living with at the age of 15, when he convinced his mother to replace the accordion she'd bought him as a birthday gift with a Danelectro electric guitar.

Five years later, after brief stints in art school and the Army, and after surviving a deadly automobile accident in 1961, he began to pursue a musical career in earnest, playing with various groups that were part of San Francisco's bluegrass and folk scene.

By 1965, he had joined up with bassist Phil Lesh, rhythm guitarist Bob Weir, organist Ron "Pigpen" McKernan and drummer Bill Kreutzman in a group originally called the Warlocks. They were later renamed "The Grateful Dead."

From their early gig as the house band at Ken Kesey's famous Acid Tests, the Dead was a defining part of San Francisco's burgeoning hippie counterculture scene. They would go on to play at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 and at Woodstock in 1969.

However, as big as they were in the 60s and 70s, the Grateful Dead grew even more popular and successful as the decade they helped to define slipped further into the past.

Indeed, during the final decade of Jerry Garcia's life, following his recovery from a five-day diabetic coma in 1986, the Dead played an average of 100 to 150 live shows per year, frequently to sold-out audiences that included a significant proportion of tie-dye-wearing college students who were not yet alive when the Grateful Dead first made their name.

Thanks History.com

Whitney Houston was born 60 years ago today.

A recording artist, actress, producer and model, Houston was one of the world's best-selling music artists, having sold over 170 million albums, singles and videos worldwide. She released seven studio albums and three movie soundtrack albums, all of which have diamond, multi-platinum, platinum or gold certification.

Houston's crossover appeal on the popular music charts, as well as her prominence on MTV, starting with her video for "How Will I Know,” influenced several African American female artists to follow in her footsteps.

Houston is the only artist to chart seven consecutive #1 Top 100 hits. She is the second artist behind Elton John and the only female artist to have two #1 Billboard 200 Album awards on the magazine’s year-end charts.

Houston's 1985 debut album, Whitney Houston, became the best-selling debut album by a female act at the time of its release. Her second studio album, Whitney, (1987) became the first album by a female artist to debut at #1 on the Billboard 200 albums chart.

Houston's first acting role was as the star of the feature film, The Bodyguard (1992). Its lead single "I Will Always Love You,” became the best-selling single by a female artist in music history.

With the album, Houston became the first act (solo or group, male or female) to sell more than a million copies of an album within a single week period under Nielsen SoundScan system. The album makes her the top female act in the top 10 list of the best-selling albums of all time, at #4.

Houston continued to star in movies and contribute to their soundtracks, including the films, Waiting to Exhale (1995) and The Preacher's Wife (1996). The Preacher's Wife soundtrack became the best-selling gospel album in history.

On February 11, 2012, Houston was found unresponsive in Suite 434 at the Beverly Hilton Hotel, submerged in the bathtub. The cause of death was ruled by the coroner to have been an "accidental drowning” due to drugs. She was 48.

Here, Houston sings “I Will Always Love You” in 1994.

Barbara Mason is 76 years old today.

Born in Philadelphia, Mason is an R&B/soul singer with several R&B and pop hits in the 1960s and 1970s, best known for her self-written 1965 hit song, "Yes, I'm Ready."

Mason initially focused on songwriting in her teens. As a performer, she had a major hit single with her third release in 1965, "Yes, I'm Ready." Her sound was rhythmic, but lush, and came to be called “Philly Soul.”

Mason had modest success throughout the rest of the decade on the small Arctic label, run by her manager, Jimmy Bishop, a Philadelphia disc-jockey. She reached the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 Top 40 again in 1965 with "Sad, Sad Girl," and "Oh How It Hurts" in 1967, releasing two albums.

A two-year stay with National General Records, run by a film production company, produced one album and four singles which failed to find success.

In the 1970s, Mason signed to Buddah Records and toughened her persona, singing about sexual love and infidelity. Her songs like "Bed and Board," "From His Woman to You" and "Shackin' Up" and would interrupt her singing to deliver straight-talking raps about romance.

Curtis Mayfield produced her on a cover version of Mayfield's own, "Give Me Your Love," which restored her to the pop Top 40 and R&B Top Ten in 1973. "From His Woman to You" (the response to Shirley Brown's single, "Woman to Woman") and "Shackin' Up," produced by former Stax producer Don Davis in Detroit, were also solid soul sellers in the mid-1970s.

After leaving Buddah Records in 1975, surprisingly after two Top 10 R&B hits, she only dented the charts periodically on small labels. They included "I Am Your Woman, She Is Your Wife," which was produced in 1978 by Weldon McDougal, who had produced her first major success, "Yes I'm Ready,” and later in 1984, "Another Man" on West End Records.

Mason started to concentrate on running her own publishing company in the late 1980s, but continues to perform occasionally.

Here, Mason performs “Yes, I’m Ready.”

Pictures in the Everglades

by Frank Beacham

(I originally wrote this article in the 1990s. Clyde Butcher’s work continues to climb in artistic stature today.)

Standing waist deep in the swamp, under attack by aggressive mosquitoes and keenly aware of the nearby alligators and snakes, I fumbled under a large piece of dark cloth to see the dim upside down image through the back of a wooden view camera.

“You know in the video world we have viewfinder hoods,” I shouted from under the thick black cover to Clyde Butcher, sweltering from the oppressive heat.

“Hoods are for wimps,” responded Butcher, one of the world's best landscape photographers. “This is Mathew Brady stuff!”

Yes, it is, I quickly realized. Photography as it was done in the 19th century, when the great Mathew Brady and his assistants lugged similar equipment around battlefields to create the most memorable images of the American Civil War.

As a member of the video generation, I found myself in a bit of a technology time warp. A world where a new fangled gadget like a viewfinder hood is looked upon with suspicion. In this branch of image making, old fashioned craft and vision reign supreme over new technology and the latest widgets.

Yet, I found going back to the basics a strangely satisfying experience. Working with 4x5 inch black and white negatives and huge, radiant high definition prints resulted in a creative high I have yet to match with the high tech tools of these digital times.

I had first gotten a glimpse of Clyde Butcher's photography in the early 1990s when I stumbled into a PBS television special about his task of preserving on film Florida's rapidly disappearing Everglades. I was instantly attracted to his work.

After calling his gallery, I found he offers occasional workshops in large format photography at his 13-acre wilderness compound in South Florida's Big Cypress National Preserve.

Butcher, whose talents at photographing nature rank up there with the late Ansel Adams, normally works with 8x10 and 12x20 format Wisner view cameras. His monochrome prints range in size from 11x14 (which he considers barely a wallet photo) to huge wall murals that are stunning in their scope, richness and detail.

Thinking Butcher's Everglades outpost would be a brief, but splendid, break from electronic media, I was surprised to find that a CBS Sunday Morning crew would be completing a video profile of the photographer on the second day of our workshop.

Ironically, I would get a side-by-side comparison of the film and video images made in the picturesque swamp and the chance to ponder the methods by which each was created.

The CBS crew set up a video viewing station in Butcher's darkroom where we were crafting the prints from negatives we had taken the day before. Their video — made efficiently and quickly — had the crisp, snappy color and technically savvy look of work done by a top professional network crew.

Yet, clearly missing from the video was the emotional bang that had drawn me to Butcher's photographs in the first place. How was it that Butcher could tell a whole story so well on a single frame of black and white film while the thousands of moving video images only skimmed the emotional surface of the subject?

Was it simply a matter of resolution? Do we not have “fine art” video because of the limitations of the television medium to resolve detail? If so, then why — after well over a decade — haven't we seen high resolution video used as a artistic medium?

If it is not the video medium itself, does the answer lie in how we've been conditioned to use it? Or does it go much deeper?

After the CBS crew had finished and was on the way to their next assignment, we in the darkroom were still tinkering with our prints, trying to decide where to dodge and burn or how to vary the contrast with filters.

Our still images were obviously produced through a much slower and more deliberate process than the video. They had a handmade quality. There was even a subtle aesthetic with the equipment itself — something I never felt before with electronics.

Take the Wisner camera. It's more like a piece of fine furniture than a technical tool. Made of beautifully finished mahogany wood with adjustable brass fittings, the camera is a timeless design. Not only does it offer a wide range of options to the creative photographer, but one could never imagine it ever becoming obsolete.

While other types of photography have succumbed to computer-assisted automation, somehow the methods of making large format landscape photographs have remained traditional. Here the human mind never relinquishes control to a computer.

The photographer must think about every step taken. Each adjustment is made by hand. Careful consideration must be made to planes of focus, depth of field and the perspective of the subject. Even then, the image on the camera's viewing surface is upside down and very dim.

From the very first day, the large format photographer assumes the role of artisan. For us video “wimps” — used to the “point and shoot” conveniences of modern cameras — it's at first hard to be confident about decisions of composition and image sharpness under that dark cloth.

Yet for an old pro like Butcher — with more than 40 years experience under his belt — these seemingly large obstacles have been turned to pluses. He uses his eyes, not the viewfinder, to frame the image. He can do this because he instinctively knows what each lens will see and how it will see it.

The slow and tedious nature of large format photography, says Butcher, forces the creator of the image to take time to think about the picture being made. Sometimes it takes Butcher hours to make a single photograph.

This contemplative method, he is quick to point out, is far more important than technique in helping convey a powerful emotional experience on a sheet of film.

One workshop participant asked Butcher what makes a visual artist. He estimated that it first takes about 20 years of learning the nuts and bolts — the techniques of image making — followed by another period when that technique is suppressed, becoming second nature.

For most of us, only then does real artistic vision begin to kick in. And even then, nothing is guaranteed. It all depends on the fragile talent and circumstances of the individual at a given moment as to whether new artistic boundaries will be broken.

In Butcher's life, the transition from successful commercial photographer to artist came in a tragic way. He says he found his creative voice in the grief that followed his son's death in an auto accident. The shock of that death led him to re-evaluate his approach to his work and resulted in his commitment to fine art nature photography.

It's a long way from a Florida swamp to an urban jungle like New York City. But in Clyde Butcher's wilderness preserve, there are valuable lessons for those who would attempt to use video as an artistic medium.

Butcher's work reminds us that the art of the picture is not found in technology or technique. It's in the mind of the maker. The only artistic limitations we face in any medium are within ourselves.

Below, Butcher and I go "swamp walking" in the Everglades in the mid 1990s.

The 1991 watercolor “On Walden Pond” is by N. Santoleri

Walden, the story by Henry David Thoreau of his life in a cabin at Walden Pond, was published on this day in 1854 — 169 years ago.

First published as “Walden; or, Life in the Woods,” the book is a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings. The work is part personal declaration of independence, social experiment, voyage of spiritual discovery, satire and (to some degree) a manual for self-reliance.

Thoreau also used this time to write his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.

First published in 1854, Walden details Thoreau's experiences over the course of two years, two months and two days in a cabin he built near Walden Pond. It was amidst woodland owned by his friend and mentor, Ralph Waldo Emerson, near Concord, Massachusetts.

The book compresses the time into a single calendar year and uses passages of four seasons to symbolize human development. By immersing himself in nature, Thoreau hoped to gain a more objective understanding of society through personal introspection.

Simple living and self-sufficiency were Thoreau's other goals, and the whole project was inspired by transcendentalist philosophy, a central theme of the American Romantic Period.

Marc Cohn, New York City, 2015

Photo by Frank Beacham

On this day in 2005 — 18 years ago — Marc Cohn survived being shot in the head during an attempted car jacking as he left a concert in Denver, Colorado.

Cohn was struck in the temple by the bullet but it did not penetrate his skull.

Police said a man tried to commandeer Cohn's tour van as it left after a show, the attacker was fleeing police after trying to pay a hotel bill with a stolen credit card.

Waylon Jennings and Buddy Holly in a photo machine