Robert Moog, inventor of the Moog synthesizer, was born 89 years ago today

Robert Moog, inventor of the Moog synthesizer, was born 89 years ago today.

Founder of Moog Music, Moog was a pioneer of electronic music. His innovative electronic design is employed in numerous synthesizers including the Minimoog Model D, Minimoog Voyager, Little Phatty, Moog Taurus Bass Pedals, Moog Minitaur and the Moogerfooger line of effects pedals.

A native of New York City, Moog attended the Bronx High School of Science in New York, graduating in 1952. He earned a bachelor's degree in physics from Queens College, New York in 1957, another in electrical engineering from Columbia University and a Ph.D. in engineering physics from Cornell University.

During his lifetime, Moog founded two companies for manufacturing electronic musical instruments. He also worked as a consultant and vice president for new product research at Kurzweil Music Systems from 1984 to 1988, helping to develop the Kurzweil K2000. He spent the early 1990s as a research professor of music at the University of North Carolina at Asheville.

Moog gave an enthusiastically-received lecture at the 2004 New Interfaces for Musical Expression, held in Hamamatsu, Japan's "City of Musical Instruments," in June, 2004. He was the inspiration behind the 2004 film, Moog.

The Moog synthesizer was one of the first widely used electronic musical instruments. He created the first voltage-controlled subtractive synthesizer to utilize a keyboard as a controller and demonstrated it at the AES convention in 1964. He is a listed inventor on ten U.S. patents.

Moog had his theremin company (R. A. Moog Co., which later became Moog Music) manufacture and market his synthesizers. Unlike the few other 1960s synthesizer manufacturers, Moog shipped a piano-style keyboard as the standard user interface.

Moog also established standards for analog synthesizer control interfacing, with a logarithmic one volt-per-octave pitch control and a separate pulse triggering signal.

The first Moog instruments were modular synthesizers. In 1971, Moog Music began production of the Minimoog Model D, which was among the first synthesizers that was widely available, portable and relatively affordable.

One of Moog's earliest musical customers was Wendy Carlos, whom he credits with providing feedback valuable to further development. Through his involvement in electronic music, Moog developed close professional relationships with artists such as Don Buchla, Keith Emerson, Rick Wakeman, John Cage, Gershon Kingsley, Clara Rockmore, Jean Jacques Perrey and Pamelia Kurstin.

In a 2000 interview, Moog said: "I'm an engineer. I see myself as a toolmaker and the musicians are my customers. They use my tools."

Moog was diagnosed with a glioblastoma multiforme brain tumor on April 28, 2005. He died at the age of 71 in Asheville, North Carolina on August 21, 2005.

Here, Moog demonstrates the Minimoog

Frank Beacham playing his assembled theremin

Building a Theremin: My Personal Odyssey

In October, 1994, at the New York Film Festival, I watched a powerful documentary by Steven M. Martin about the creation of the world's first electronic musical instrument.

Billed as part biography, part social history and part detective story, the film — "Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey" — told the remarkable story of Leon Theremin, a Russian-born inventor whose adventures spanned the avant garde music world in New York City in the 1920s to the clandestine world of the KGB in the 1930s and 40s.

In 1922, Theremin demonstrated an early version of his strange new music machine for Nikolai Lenin, the U.S.S.R.'s leader. Five years later, he played his instrument for a group of American VIPs in the Grand Ballroom of the Plaza Hotel in New York City. It was received into America's Jazz Age culture with awe and excitement.

The original theremin, which resembled a wooden speakers' podium with a loop of metal extending from one side and a vertical metal antenna on the other, was a real curiosity in the early radio days.

Audiences were mesmerized by a new breed of instrument whose music was generated not from physical contact but from hand movements made in the air around the two protruding antennas.

By controlling the pitch with the right hand and the volume with the left, it's possible to create music that suggests — as the New York Times put it — "a violin or a soprano or a Martian making a landing. It is surpassingly strange."

For about two years beginning in 1929, RCA manufactured and sold 500 theremins. From 1930 until his mysterious disappearance in 1938, Leon Theremin built the instruments for customers in his New York studio on West 54th Street.

That disappearance makes the Theremin legend even more strange and fascinating.

The inventor was apparently kidnapped by Soviet agents from his New York establishment and taken to Russia where, after a period of imprisonment, he was engaged by the government to design electronic eavesdropping technology for spies in World War II.

Long assumed dead in the West (a German newspaper reported his demise), he was spotted by chance one day at the Moscow Conservatory of Music by a visiting reporter for the New York Times. This led to his emotional return to the United States in 1991 (an event portrayed in the film).

Whether we realize it or not, most of us are familiar with the wavering vibrato sound of the theremin from dozens of 1950's-era science fiction and horror movies. Films like Spellbound, The Lost Weekend and The Day the Earth Stood Still used theremins on their soundtracks. The Beach Boys' Good Vibrations is perhaps the best known use of a theremin in a pop music recording.

The theremin caught the imagination of Robert Moog, who started building the instruments as a teenager and began to manufacture them again for sale in 1954 — 16 years after Leon Theremin's disappearance. A decade later Moog made music history when he invented the Moog synthesizer, the first in a successful line of electronic music synthesizers.

I met Moog at the film festival and quickly became enamored by the theremin. At the time, Moog made theremins at Big Briar, Inc., his company located in the mountains of Asheville, North Carolina.

Taking advantage of the explosion of new interest in theremins after the release of the film, Moog introduced an affordable Theremin called the Etherwave. It was a no compromise, fully professional instrument that had the tone color and playing characteristics of Theremin's original. A Etherwave kit cost $229 at the time.

Nostalgic for my old Heathkit days and fascinated by the idea of owning such an oddball instrument (though I had no ability to play it), I purchased an Etherwave kit from Big Briar. It came with an unfinished wood cabinet, nickel-plated brass antennas, a pre-assembled circuit card, a power supply and several bags of parts. Also included was an instructional video and a CD of theremin music by the inventor's protégé, Clara Rockmore.

The Big Briar brochure said "if you can read a diagram, solder and use basic home tools, you should be able to build this theremin in an evening or two." As with Heathkits, Big Briar (actually Robert Moog personally) didn’t let me fail. I got Moog on the phone a couple of times and he was most helpful. He nursed me through the project. When I turned on the power switch of the Etherwave, it worked perfectly.

When I finished the kit, I asked Robert Moog if he could explain why such a cult-like following has developed around this instrument — with more than 50 professional musical acts at the time using theremins in performance throughout the world.

Moog said several factors contributed to its appeal. "For one thing the instrument is responsive," he said. "With a keyboard you put your finger on a key and the note plays. That's it. This is just the opposite. The note keeps changing with every single motion of your hand. People like that. They enjoy that responsiveness.

"Another part of it," he continued, "is that's all in the air. There's something ethereal about that. Something gossamer. Back in the earlier days it was an elitist thing. It was rather sensational, but there were very few people who actually got up and played it. Now that's changed. It's much better established now than in the past. People are engrossed in it. It's almost a cult thing."

(P.S. Though I sold my home-built theremin to a professional musician who could play it, I'm still fascinated by the instrument. Now I have a theremin ring tone on my iPhone. People do a doubletake every time it rings!)

Betty Garrett with Jack Lemon in My Sister Eileen, 1955

Betty Garrett: A Personal Story

Garrett, born 104 years ago today, was an actress, comedienne, singer and dancer who originally performed on Broadway before being signed to a film contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. While there, she appeared in several musical films before returning to Broadway and making guest appearances on several television series.

Later, she became known for the roles she played in two prominent 1970s sitcoms: Archie Bunker's liberal neighbor, Irene Lorenzo, in All in the Family and landlady, Edna Babish, in Laverne & Shirley.

Very early in her career, Garrett also performed with Orson Welles’s Mercury Theatre company during the production of Danton’s Death in the 1930s. Her fellow cast members were Joseph Cotten, Ruth Ford, Martin Gabel and Arlene Francis.

In 2001, Garrett returned to Broadway to perform in a revival of Follies at the Belasco Theatre in New York.

I wanted to interview Garrett for an Orson Welles project I was working on. So I sent a letter and flowers to her backstage at the theatre. It worked!

After a performance of Follies, Ms. Garrett invited me, along with my writing partner, George Demas, to a coffee shop near the theatre. She was gracious and talkative and we had wonderful evening.

One story sticks with me. Garrett made her Broadway debut in 1942 in the revue, Of V We Sing. One day while sitting in her dressing room, a security guard called her and said two kids who were trying to sneak into the theatre had used her name when they were caught. She asked the guard to bring them to her dressing room.

Garrett said the young men had no money, but had wanted to see her perform. Instead, they got caught.

Feeling sorry for them, Garrett told them to come back at performance time and she would leave their names and comp tickets at the box office. The kids got very excited and thanked her profusely. Garrett forgot about the incident.

Thirty-one years later, in the fall of 1973, while grocery shopping in LA, a man approached her in the market and told her he was one of the kids she had let in the theatre in New York. Moved, she gave the man tickets for he and his friend to a one-person show she was doing in LA. at the time.

After that show, the two men came back stage to meet her. They told her they were now writers for the hit sitcom, All in the Family, and asked her to audition for a new regular cast member on the show. She auditioned and got the part. This, she said, opened the door to an entire new second career for her on television.

The moral to the story, she said, is to be nice to everyone along life’s journey. You never know when the smallest act of kindness will change your future and result in a profound effect on your life.

Betty Garrett died of an aortic aneurysm in Los Angeles on February 12, 2011 at the age of 91.

Her autobiography, Betty Garrett and Other Songs: A Life on Stage and Screen, is outstanding. It is a book about life in the theatre and the cruel damage done by the Hollywood Blacklist.

A great read!

George Claude, circa 1926

Georges Claude, French inventor who died on this day in 1960, discovered a mechanism to trap gas in a tube and zap it with electricity. His invention is now better known as neon — the technology that spawned millions of neon signs.

Claude’s invention turned the ordinary extraordinary. Called the Edison of France, Claude demonstrated his neon invention at the Paris Motor Show in 1910 with two 40-foot tubes that glowed a brilliant orange-red. Two years later, he installed the first neon advertising sign in a barbershop on the Boulevard Montmartre in Paris.

Neon lighting took off, and became an important cultural phenomenon in the United States. By 1940, the downtowns of nearly every U.S. city were bright with neon signage. Times Square in New York City was known worldwide for its neon extravagances. There were 2,000 shops nationwide designing and fabricating neon signs.

The popularity, intricacy and scale of neon signage for advertising declined in the U.S. following the Second World War (1939–1945), but development continued vigorously in Japan, Iran and some other countries. In recent decades, architects and artists, in addition to sign designers, have again adopted neon tube lighting as a component in their works.

Several museums in the United States are now devoted to neon lighting and art, including the Museum of Neon Art (founded by neon artist Lili Lakich, Los Angeles, 1981), the Neon Museum (Las Vegas, founded 1996), the American Sign Museum (Cincinnati, founded 1999) and the Neon Museum of Philadelphia (founded by Len Davidson, Philadelphia, 1985).

These museums restore and display historical signage that was originally designed as advertising, in addition to presenting exhibits of neon art. Several books of photographs have also been published to draw attention to neon lighting as art. In 1994, Christian Schiess published an anthology of photographs and interviews devoted to fifteen “light artists.”

Thanks New York Times!

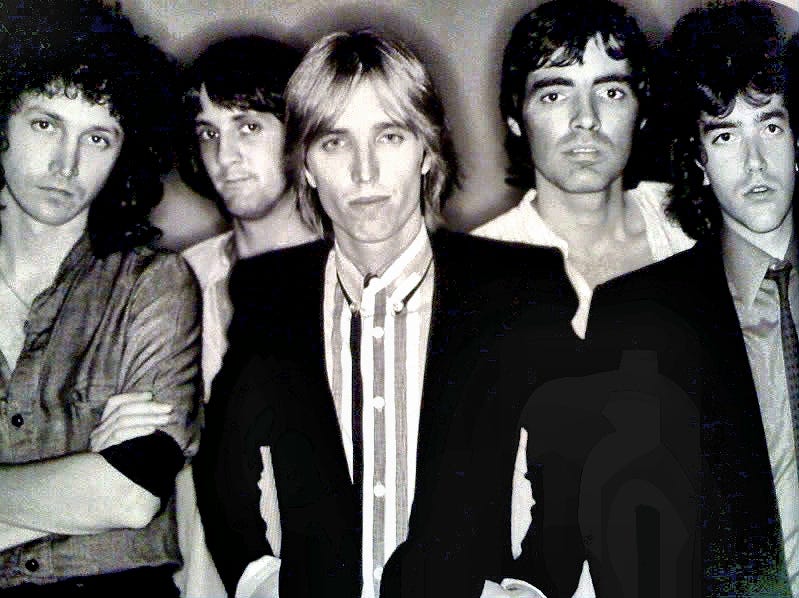

Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers, 1979

The music industry was notorious for its creative accounting practices and for onerous contracts that could keep even some top-selling artists perpetually in debt to their record labels. In a typical recording contract back in the day, a record label advanced an artist a certain sum of money against future earnings from royalties.

But because the cost of things like studio time, marketing support and tour expenses must be "recouped" by the label before an artist earned any royalties, many artists who signed recording contracts never sold enough records to "earn out" their advance.

Where this system truly broke down was when a top-selling artist or group like TLC or Run-DMC found itself deeply in debt to its record label despite having sold millions of records.

Those are but two groups that pursued a strategy made famous by Tom Petty when he declared bankruptcy on this day in 1979 — 44 years ago — in an effort to free himself from his contract with Shelter Records.

At the time of Tom Petty's bankruptcy filing, he had little to show financially for the two hit albums already behind him: 1976's Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers (featuring the hit singles "Breakdown" and "American Girl") and 1978's You're Gonna Get It!

Unhappy with the terms of his contract with Shelter Records, Petty seized upon the sale of Shelter by ABC to industry giant MCA as justification to declare himself, in effect, a free agent.

In his own words, he would not be "bought and sold like a piece of meat." (Never mind the fact that the deal was actually a re-acquisition, since Shelter — and with it Petty's contract — had actually been owned by MCA before being acquired by ABC.)

Petty refused to allow his next album to be released, even going so far as to bear the cost of recording it personally, leaving him some $500,000 in debt. This was when he filed for bankruptcy, hoping to gain leverage in the brewing legal dispute by having the bankruptcy court declare null and void an extremely unfavorable contract that Petty felt he had signed under duress.

Ultimately, MCA blinked, agreeing to release Petty from his existing contract but immediately re-signing him to a $3 million contract with a brand-new subsidiary label created especially for this purpose.

The album that Petty had held back, Damn The Torpedoes (featuring the singles "Refugee" and "Don't Do Me Like That"), would go on to be certified Double Platinum and make Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers into true superstars.

But if MCA thought that its squabbles with Petty were behind them at that point, they were sorely mistaken. In 1981, Petty once again threatened to withhold his new album, Hard Promises, when MCA announced its intention to sell it for $9.98 — a full dollar more than the typical retail price at the time.

"If we don't take a stand, one of these days records are going to be $20," Petty said at the time. And once again, MCA finally agreed, selling the album at retail for the then-customary $8.98.

Here, Petty performs “Refugee” from Damn the Torpedoes in 1985

Thanks History.com

Artie Shaw was born 113 years ago today.

A clarinetist, composer and bandleader, Shaw was also an author who wrote both fiction and non-fiction. Widely regarded as "one of jazz's finest clarinetists," Shaw led a popular big band in the late 1930s through the early 1940s.

The band’s signature song, a 1938 version of Cole Porter's "Begin the Beguine," was wildly successful and one of the era's defining recordings. Musically restless, Shaw was also an early proponent of Third Stream, which blended classical and jazz. He recorded some small-group sessions that flirted with be-bop before retiring from music in 1954.

In addition to hiring Buddy Rich, Shaw signed Billie Holiday as his band's vocalist in 1938. He became the first white bandleader to hire a full-time black female singer to tour the segregated Southern United States.

However, after recording "Any Old Time," she left the band due to hostility from audiences in the South, as well as from music company executives who wanted a more "mainstream" singer. His band became enormously successful, and his playing was eventually recognized as equal to that of Benny Goodman. Longtime Duke Ellington clarinetist Barney Bigard cited Shaw as his favorite clarinet player.

In response to Goodman's nickname, the "King of Swing," Shaw's fans dubbed him the "King of the Clarinet." Shaw, however, felt the titles were reversed. "Benny Goodman played clarinet. I played music," he said.

In 1938, DownBeat Magazine's readers agreed with Shaw's evaluation and named Artie Shaw as the King of Swing. Shaw took himself seriously as an artist and valued experimental and innovative music rather than generic dance and love songs, despite an extremely successful career that sold more than 100 million records.

He fused jazz with classical music by adding strings to his arrangements, experimented with bebop and formed "chamber jazz" groups that utilized such novel sounds as harpsichords or Afro-Cuban music.

Shaw died in 2004 at the age of 94.

Here Artie Shaw performs Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine”

Mac Wiseman was born 98 years ago today.

A bluegrass singer, nicknamed “The Voice with a Heart,” Wiseman was one of the cult figures of bluegrass.

Born in Crimora, Virginia, he studied at the Shenandoah Conservatory in Dayton, Virginia — before it moved to Winchester, Virginia in 1960. He started his career as a disc jockey at WSVA-AM in Harrisonburg, Virginia.

Wiseman’s musical career began as upright bass player in the band of country singer, Molly O'Day. When Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs left Bill Monroe's band, Wiseman became the guitarist for their new band, the Foggy Mountain Boys. Later he played with Bill Monroe's Bluegrass Boys.

After a performance on Louisiana Hayride, he became popular as solo artist. In the 1950s, he was the star of The Old Dominion Barn Dance on WRVA in Richmond, Virginia.

During the folk revival in the 1960s, Wiseman performed successful concerts at the Hollywood Bowl and Carnegie Hall. He joined producers Randall Franks and Alan Autry for the In the Heat of the Night cast CD, Christmas Time’s A Comin,’ released on Sonlite and MGM/UA. It became one of the most popular Christmas releases of 1991 and 1992.

Wiseman’s substantial girth and light tenor voice gave rise to the quip that "Mac Wiseman sings like Gene Vincent looks, and looks like Ernest Tubb sings."

Wiseman died in Nashville on February 24, 2019. The cause of death was kidney failure.

Here, Wiseman performs “Jimmie Brown The Newsboy”