Richard Avedon, fashion and portrait photographer, was born 100 years ago today

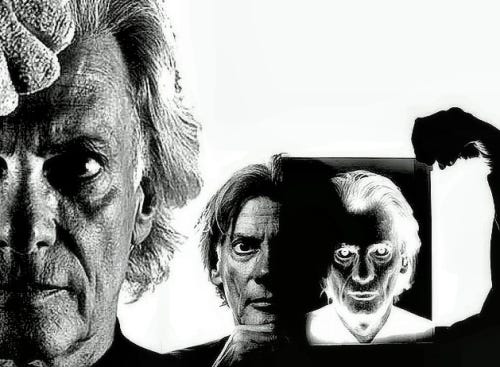

Richard Avedon self portrait

Richard Avedon, fashion and portrait photographer, was born 100 years ago today.

Born in New York City to a Jewish family, Avadon’s father, Jacob Israel Avedon, was a Russian-born immigrant who advanced from menial work to starting his own successful retail dress business on Fifth Avenue —Avedon’s Fifth Avenue. His mother, Anna, from a family that owned a dress-manufacturing business, encouraged her son’s love of fashion and art.

Avedon’s interest in photography emerged when, at age 12, he joined the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) Camera Club. He would use his family’s Kodak Box Brownie not only to feed his curiosity about the world, but also to retreat from his personal life.

The photographer's first muse was his younger sister, Louise, a beautiful subject. During her teen years, however, she struggled through psychiatric treatment. And, eventually, becoming increasingly withdrawn from reality, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia. These early influences of fashion and family would shape his life and career, often expressed in his desire to capture tragic beauty in photos.

Avedon attended DeWitt Clinton High School in Bedford Park, Bronx, where he worked on the school paper, The Magpie, with James Baldwin from 1937 until 1940. In addition to his continued interest in fashion and photography, Avedon developed an affinity for poetry.

In 1941, his senior year of high school, he was named Poet Laureate of New York City High Schools. After graduating from DeWitt that year, he enrolled at Columbia University to study philosophy and poetry but dropped out after one year. He then started as a photographer for the Merchant Marines, taking ID shots of the crewmen with the Rolleiflex camera his father had given him as a gift.

From 1944 to 1950, Avedon studied photography with Alexey Brodovitch at his Design Laboratory at the New School for Social Research.

In 1944, Avedon began working as an advertising photographer for a department store, but was quickly endorsed by Alexey Brodovitch, the art director for the fashion magazine, Harper's Bazaar.

Lillian Bassman also promoted Avedon's career at Harper's. In 1945, his photographs began appearing in Junior Bazaar and, a year later, in Harper's Bazaar.

In 1946, Avedon had set up his own studio and began providing images for magazines including Vogue and Life. He soon became the chief photographer for Harper's Bazaar. From 1950, he also contributed photographs to Life, Look and Graphis and, in 1952, became staff editor and photographer for Theatre Arts Magazine.

Avedon did not conform to the standard technique of taking studio fashion photographs, where models stood emotionless and seemingly indifferent to the camera. Instead, Avedon showed models full of emotion, smiling, laughing and, many times, in action in outdoor settings, which was revolutionary at the time.

However, towards the end of the 1950s, he became dissatisfied with daylight photography and open air locations and so turned to studio photography, using strobe lighting.

When Diana Vreeland left Harper's Bazaar for Vogue magazine in 1962, Avedon joined her as a staff photographer. He proceeded to become the lead photographer of Vogue and photographed most of the covers from 1973 until Anna Wintour became editor in late 1988.

Notable among his fashion advertisement photograph series are the recurring assignments for Gianni Versace, starting from the spring/summer campaign 1980. He also photographed the Calvin Klein Jeans campaign featuring a fifteen-year-old Brooke Shields, as well as directing her in the television commercials.

Avedon first worked with Shields in 1974 for a Colgate toothpaste ad. He shot her for Versace, 12 American Vogue covers and Revlon's Most Unforgettable Women campaign.

In the February 9, 1981, issue of Newsweek, Avedon said that "Brooke is a lightning rod. She focuses the inarticulate rage people feel about the decline in contemporary morality and destruction of innocence in the world."

On working with Avedon, Shields told Interview magazine in May, 1992 "when Dick walks into the room, a lot of people are intimidated. But when he works, he's so acutely creative, so sensitive. And he doesn't like it if anyone else is around or speaking. There is a mutual vulnerability, and a moment of fusion when he clicks the shutter. You either get it or you don't."

By the 1960s, Avedon had turned his energies toward making studio portraits of civil rights workers, politicians and cultural dissidents of various stripes in an America fissured by discord and violence. He began to branch out and photographed patients of mental hospitals, the Civil Rights Movement in 1963, protesters of the Vietnam War and later the fall of the Berlin Wall.

An exceedingly personal book called “Nothing Personal,” with a text by his high school classmate James Baldwin appeared in 1964.

During this period, Avedon also created two famous sets of portraits of The Beatles. The first, taken in mid to late 1967, became one of the first major rock poster series, and consisted of five striking psychedelic portraits of the group — four heavily solarized individual color portraits (solarization of prints by his assistant, Gideon Lewin, retouching by Bob Bishop) and a black-and-white group portrait taken with a Rolleiflex camera and a normal Planar lens. The next year he photographed the much more restrained portraits that were included with The Beatles in 1968.

Avedon was always interested in how portraiture captures the personality and soul of its subject. As his reputation as a photographer became widely known, he brought in many famous faces to his studio and photographed them with a large-format 8x10 view camera. His subjects included Buster Keaton, Marian Anderson, Marilyn Monroe, Ezra Pound, Isak Dinesen, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Andy Warhol and the Chicago Seven.

His portraits are easily distinguished by their minimalist style, where the person is looking squarely in the camera, posed in front of a sheer white background. By eliminating the use of soft lights and props, Avedon was able to focus on the inner worlds of his subjects evoking emotions and reactions. He would at times evoke reactions from his portrait subjects by guiding them into uncomfortable areas of discussion or asking them psychologically probing questions.

Through these means he would produce images revealing aspects of his subject's character and personality that were not typically captured by others.

His mural groupings featured emblematic figures: Andy Warhol with the players and stars of The Factory; The Chicago Seven, political radicals charged with conspiracy to incite riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention; the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and his extended family; and the Mission Council, a group of military and government officials who governed the United States' participation in the Vietnam War.

Avedon became the first staff photographer for The New Yorker in 1992, where his post-apocalyptic, wild fashion fable “In Memory of the Late Mr. and Mrs. Comfort,” featuring model Nadja Auermann and a skeleton, was published in 1995.

Other pictures for the magazine, ranging from the first publication, in 1994, of previously unpublished photos of Marilyn Monroe to a resonant rendering of Christopher Reeve in his wheelchair and nude photographs of Charlize Theron in 2004, were topics of wide discussion.

Some of his less controversial New Yorker portraits include those of Saul Bellow, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Toni Morrison, Derek Walcott, John Kerry and Stephen Sondheim.

Serious heart inflammations hindered Avedon’s health in 1974. The troubling time inspired Avedon to create a compelling collection from a new perspective.

In 1979, Avedon was commissioned by Mitchell A. Wilder (1913–1979), the director of the Amon Carter Museum to complete the “Western Project.”

Wilder envisioned the project to portray Avedon’s take on the American West. It became a turning point in Avedon’s career when he focused on everyday working class subjects such as miners soiled in their work clothes, housewives, farmers and drifters on larger-than-life prints instead of a more traditional options with famous public figures or with the openness and grandeur of the West.

The project itself lasted five years concluding with an exhibition and a catalog. It allowed Avedon and his crew to photograph 762 people and expose approximately 17,000 sheets of 8x10 Tri-X Pan film.

The collection identified a story within his subjects of their innermost self, a connection Avedon admits would not have happened if his new sense of mortality through severe heart conditions and aging hadn’t occurred. Avedon visited and traveled through state fair rodeos, carnivals, coal mines, oil fields, slaughter houses and prisons to find the right subjects to reveal.

In 1994, Avedon revisited his subjects who would later on open up about the In the American West aftermath and its direct effects. Billy Mudd, who was a trucker, went long periods of time on his own away from his family. He was a depressed, disconnected and lonely man before Avedon offered him the chance to be photographed.

When he saw his portrait for the first time, Mudd saw that Avedon was able to reveal Mudd’s true-self and recognized the need for change in his life. The portrait transformed Billy and led him to quit his job and return to his family.

On October 1, 2004, Avedon died in a San Antonio, Texas hospital of complications from a cerebral hemorrhage. He was in San Antonio shooting an assignment for The New Yorker.

At the time of his death, he was also working on a new project titled, Democracy, to focus on the run-up to the 2004 U.S. presidential election.

Richard Avedon — A Personal Encounter

It was about 1 p.m. on a Sunday afternoon in 1994 when I went to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City to see an exhibition of Richard Avedon’s photography.

The day was young and a crowd had not yet gathered at the exhibit. I lingered in one section, fascinated by the raw beauty of Avedon’s images from the American West.

On the surface, the images were so simple in appearance, but any photographer with a minimum of training knew there was much, much more to these works than at first met the eye.

A woman stood next to me, examining one of the photographs. As I intently studied the photograph, I asked her a question, wondering about Avedon’s intent. Before she could speak, a voice from behind both of us answered the question.

I turned around and it was Richard Avedon, himself.

For the next hour, Avedon walked us through the exhibit and told stories of each photograph. He was very casual, friendly and answered all our questions.

Few people recognized Avedon. We picked up a few others along the way during the talk, but there was never more than five people. It was a remarkable experience.

A security guard later told me that Avedon often just showed up at the exhibit, usually early on Sundays, and did impromptu tours with interested visitors. He assured me I was very, very lucky.

From that moment on, I became a far bigger fan of Avedon’s work and followed him closely for the rest of his life. It was a one in a million encounter — the kind of thing that happens only in New York City.

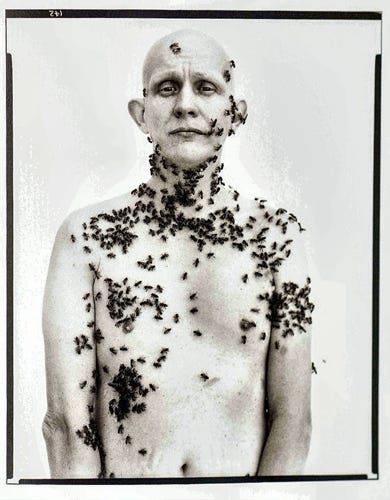

Above, one of the photographs that Avedon showed us that day. It’s Ronald Fischer, beekeeper, in Davis, California. The image was taken on May 9, 1981.

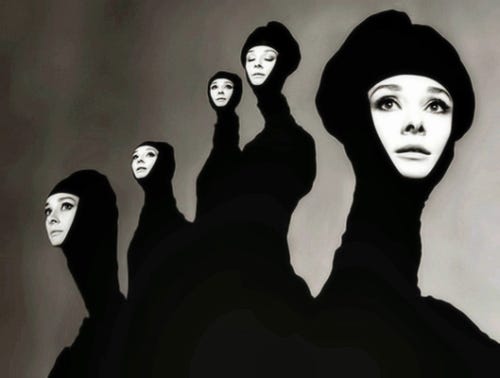

Audrey Hepburn, New York City, January, 1967