On this day in 1947 — 77 years ago today — U.S. Air Force Captain Chuck Yeager became the first person to fly faster than the speed of sound

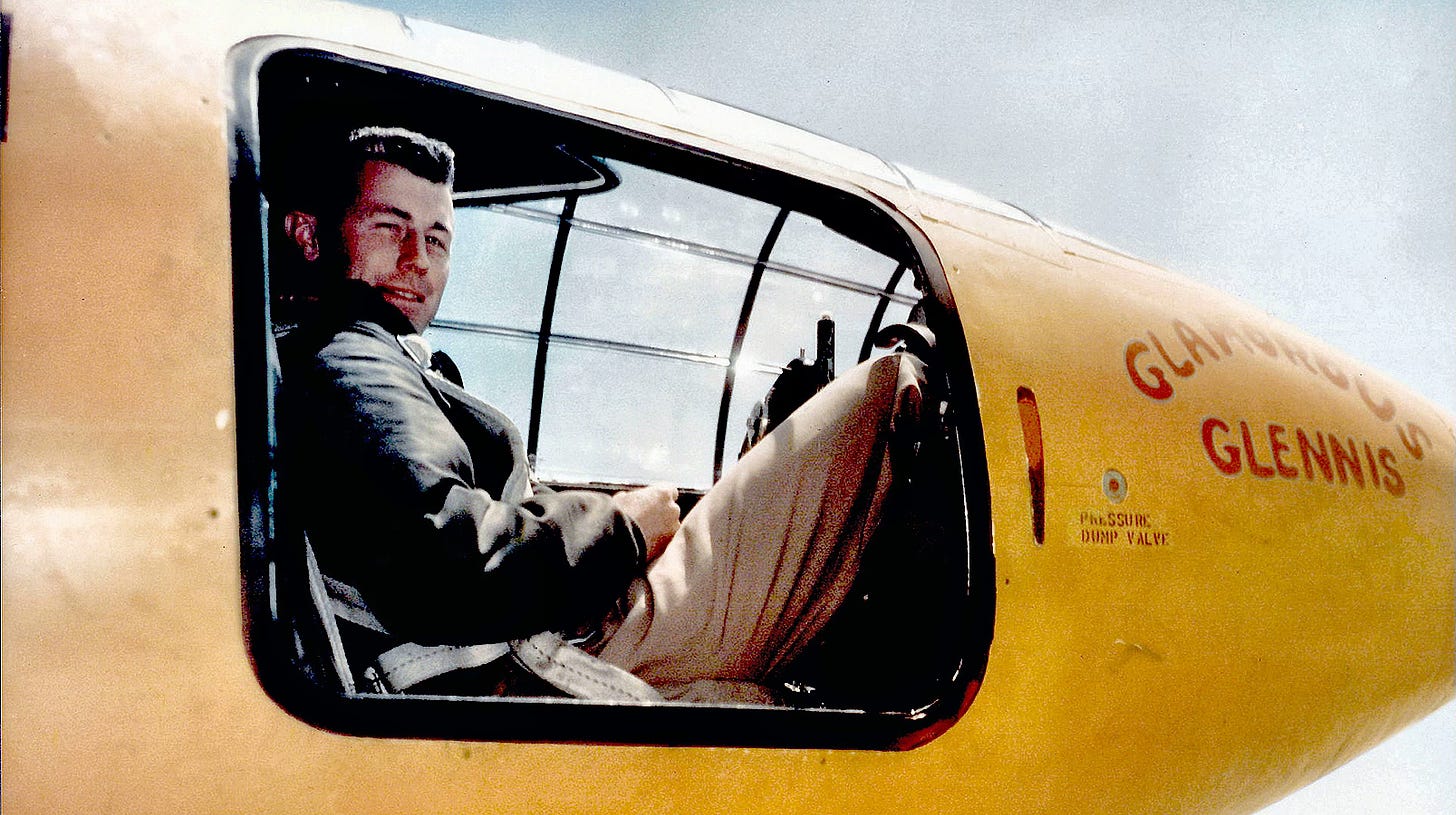

Chuck Yeager in the Bell X-1, in which he broke the sound barrier 76 years ago today. The “Glamorous Glennis” is named after his wife.

Photo by Jack Ridley

On this day in 1947 — 77 years ago today — U.S. Air Force Captain Chuck Yeager became the first person to fly faster than the speed of sound.

Yeager, born in Myra, West Virginia, in 1923, was a combat fighter during World War II and flew 64 missions over Europe. He shot down 13 German planes and was himself shot down over France, but he escaped capture with the assistance of the French Underground.

After the war, he was among several volunteers chosen to test-fly the experimental X-1 rocket plane, built by the Bell Aircraft Company to explore the possibility of supersonic flight.

For years, many aviators believed that man was not meant to fly faster than the speed of sound, theorizing that transonic drag rise would tear any aircraft apart.

All that changed on October 14, 1947, when Yeager flew the X-1 over Rogers Dry Lake in Southern California.

The X-1 was lifted to an altitude of 25,000 feet by a B-29 aircraft and then released through the bomb bay, rocketing to 40,000 feet and exceeding 662 miles per hour (the sound barrier at that altitude).

The rocket plane, nicknamed "Glamorous Glennis," was designed with thin, unswept wings and a streamlined fuselage modeled after a .50-caliber bullet. Because of the secrecy of the project, Bell and Yeager's achievement was not announced until June, 1948.

Yeager continued to serve as a test pilot, and in 1953 he flew 1,650 miles per hour in an X-1A rocket plane. He retired from the U.S. Air Force in 1975 with the rank of brigadier general.

Ironically, Yeager had to fly the mission with two cracked ribs because of a horseback riding accident. In an essay published in 1987, he described how it felt to fly past a barrier that some thought couldn’t be survived: “There was no buffet, no jolt, no shock. Above all, no brick wall to smash into. I was alive.”

He retired from the Air Force in 1975 with the rank of brigadier general and later wrote a best-selling autobiography.

On October 14, 2012, on the 65th anniversary of breaking the sound barrier, Yeager did it again at the age of 89, riding in a McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle piloted by Captain David Vincent out of Nellis Air Force Base in southern Nevada.

Yeager died at age 97 on Dec. 7, 2020.

Thanks History.com and the New York Times!

Charlie Moore and the Dixie Partners

Personal Memories of Charlie Moore

I was in the tenth grade of high school when I ventured one Saturday to the local radio station, WHPB, in nearby Belton, South Carolina. It was a few minutes drive from my home in Honea Path and I drove my old 1942 Willys army jeep to the station parking lot.

Being the weekend, there was only one person there — the on-air DJ — who was doing his shift. Through the glass control room window facing the outer lobby, he motioned me inside.

I introduced myself. He was a friendly fellow and introduced himself as Charlie Moore. It was a quiet time at the studio and he engaged me in conversation. I told him I was in high school and wanted to work in radio part-time.

“How do I get a job here?” I asked.

Learn the ropes, Charlie responded. Then he handed me the opportunity of a lifetime. I was welcome to hang out and watch what he did. Maybe if I picked enough skills, I could get hired at the station. That’s all I needed to hear.

Every weekend in the following weeks, I joined Charlie Moore on his shift. I learned a few things about him that I used to my advantage. When he wasn’t working at the radio station, Charlie was on the road singing bluegrass music.

Musicians made very little money performing in those days and Charlie needed the salary from the radio job, as well as the station’s studio facilities to record his music.

I also noted that Charlie was always tired and was taking amphetamine pills. I soon learned that if I could run the audio board and play the records, it would allow Charlie to lie on the couch and take catnaps between records.

I had found my entrée into radio.

I became so proficient at letting Charlie sleep that I would often wake him just before he had to go on the air. I’d hold a microphone over him while he lay on the couch, and he’d introduce the next record.

I quickly won a friend in Charlie Moore, who appreciated a young kid doing all the dirty work while letting him catch a few winks. As I gained more skills, Charlie had me run the audio board and record his music in the studio.

Whether the station management knew or didn’t know about these recordings, I’ll never know. But on weekends, when no one else was around, the studio would suddenly fill with bluegrass musicians.

In the studio at WHPB, we had a classic RCA 44BX ribbon microphone in a small studio connected to an RCA audio board and Roberts and Magnacord reel-to-reel tape recorders. It was a similar set-up in that era to the Sun or Stax Studios where some great music was being recorded only a few hours away.

Performers could stand all around the big microphone and sing, moving in and out as they did solo parts. I recorded hours of mono recordings of Charlie and his band members this way.

It would be forty years later before I would learn that many of those players were members of Bill Monroe’s great band, the Blue Grass Boys. And the tapes I recorded then were made into records that are still played on jukeboxes to this day. Charlie told me very little about what was really going on.

I had completely lost touch with Charlie Moore when I began to look into his life. I was surprised at what I didn’t know. When we worked together, I knew nothing of his major musical and songwriting talent. I knew him only in the context of the radio station.

Searching on the internet, I discovered that Travers Chandler, a professional bluegrass musician whose band, Avery County, is based in the Asheville, North Carolina area, has written about Charlie Moore. In fact, Travers Chandler revers Charlie, crediting him as a major influence in his own career. I called Travers to ask about Charlie.

“When I heard him sing on Truck Drivers Queen, I knew I wanted to be a bluegrass entertainer, but even more importantly I wanted to SING like Charlie Moore,” Travers told me.

In fact, Traver’s band, Avery County, was named as a tribute after a Charlie Moore album by the same name. Travers never knew Charlie personally, but his father did. They were drinking buddies.

When I worked with Charlie Moore at WHPB, he was in his late 20s. Only a year or two earlier, he had teamed with Bill Napier, a former member of the Clinch Mountain Boys. Moore and Napier signed a recording contract with King Records and began performing on television in Greenville and Spartanburg S.C., and in Panama City, Florida.

I remember watching Charlie on television early in the morning before going to school. It was hard for me to grasp his grueling life and his constant working schedule.

He would be up at 5 a.m. to do the TV show and then out in the evening to play personal appearances. On weekends, he would work at WHPB. At least I better understand why he was always tired and taking those pills.

Charlie never introduced me to the musicians I recorded, but there’s a good chance I also recorded he and Bill Napier.

“I know there were lots of people who recorded in Belton at WHPB who were members of Bill Monroe's band. Many essential recordings of legends were made in places like Belton, and at little radio stations in Virginia and North Carolina,” Travers told me.

“I know that Carl Story recorded some there in the 1960s and there’s a good chance that you recorded a bunch of stuff there that ended up on vinyl that people seek out today. I have to believe that Charlie had a hand in it, because Charlie and Carl were tight at one time,” Travers continued.

“You didn't know then what you were part of. It was legendary. At that time, musicians were starving to death. The tapes recorded at the radio stations would be sent to the record labels by the artists they were working with and would be pressed and released. Typically as 45s. A lot of times, it was just a wink and nod with the stations. Sometimes the stations were fine with it.”

At the time a lot of bands were working out of radio stations. In the late 50s and early 60s, bluegrass music almost perished. If an artist was making a record, it was on a shoestring budget type deal where little or no money was provided for recording or expenses or anything else.

Travers told me that even Bill Monroe didn't make much money in those days. “Bill was a stubborn man. He had a painful childhood. He was guarded in everything he did. He didn't trust anybody. And he was not a businessman. It wasn’t until the mid to late 1960s that he trusted someone enough to be his manager did he make any money.

“As to his band, back in those days it was a lot of swap and go. In the early 60s, somebody would leave the Stanley Brothers and go to work with Charlie and Bill Napier. Then they’d go work for Monroe or Stanley, then they’d get tired of that and come back. That’s just the way it was.”

Charlie Moore was close friends with Carter Stanley, one of the Stanley Brothers. “Carter was Charlie’s idol. Charlie wanted to be just like Carter. Both went out the same way. Carter drank himself to death at 41. Charlie drank himself to death at 44,” Travers said.

“When Charlie and Bill Napier broke up in about 1968, Charlie went to radio full time and became an MC at bluegrass shows and festivals. Charlie remained tight with everybody. He was friends with Ralph Stanley.”

Travers said he talked with Ralph Stanley about Charlie. “Ralph said my brother and Charlie Moore were the two greatest songwriters I've ever seen.”

Ironically, the great James Brown, who was also on King Records, ran the audio board for Charlie and Bill Napier in the Cincinnati, Ohio studio in the early days.

“Charlie would arrive at King and have to record 12 songs and wouldn't have any material,” Travers said. “Charlie was worn out. There was a coffee shop across the street and Charlie and Bill would go over there, sit down, and Charlie would write songs on a napkin. In an hour or so, he'd have 10 or 12 songs and they'd go the studio and work with the band. Bill Napier would come up with the melody and then they’d cut the record.”

In the mid 1970s, Charlie continued to struggle in the U.S. but began to find a following in Europe in places like Belgium, France and Holland. His luck, however, ran out.

He began drinking heavily and looked old and frail by his early 40s. Charlie became ill on the way to a show in West Virginia. Taken to a hospital, he went into a coma. He died on Christmas Eve, 1979.

Ironically, Charlie Moore gave me an entry into an industry that became my life’s work, but I never knew his story until I hit my 60s. I only knew him as an incredibly nice guy who took the time to help a kid. Little did I know that he was a brilliant songwriter and musician and would leave behind stacks of unrecorded songs.

Bluegrass musician Jimmy Martin told Travers Chandler that Charlie Moore was one of the greatest singers ever in bluegrass and country music. Charlie could have been a country star in the 1960s, Martin said, but he refused to stray from what called his old time “hillbilly” music.

“Charlie almost came along at the wrong time,” Travis noted. “There was money to be made in those days. But he was always a step behind. It was a hard luck career.”

My work at WHPB won me a South Carolina State Broadcasters Association scholarship to the University of South Carolina. It was my ticket out of the tiny town of Honea Path.

After I left in 1966, I never spoke to Charlie Moore again. It took nearly 43 years for me to learn his story.

Frank Beacham, WHPB, Belton, S.C. 1965

Charlie Moore performs “Over in Glory Land.”

Justin Hayward of the Moody Blues is 77 years old today.

An English singer, songwriter and guitarist, Hayward was born in Dean Street, Swindon, Wiltshire, England and educated at Shrivenham School, Berkshire and The Commonweal School, in Swindon.

When Hayward was 15, he was able to afford a Gibson guitar and a Vox amplifier through performing with local Swindon groups in clubs and dance halls playing mostly Buddy Holly songs.

One of Hayward's early groups was All Things Bright, which opened for The Hollies and Brian Poole and the Tremeloes.

At age 17, he signed a publishing contract as a songwriter with the skiffle artist and record producer, Lonnie Donegan, a move Hayward later regretted as it meant the rights to all his songs written before 1974 would always be owned by Donegan's Tyler Music.

In 1965, he answered an advertisement in Melody Maker and auditioned as guitarist for Marty Wilde and he went on to work with Wilde and his wife in The Wilde Three.

In 1966, after answering another ad in Melody Maker, this time placed by Eric Burdon of The Animals, Hayward was contacted by Mike Pinder of The Moody Blues after Burdon had passed on Hayward's letter and demo discs to Pinder.

Within a few days, Hayward had replaced departing Moody Blues vocalist and guitarist, Denny Laine. Bassist John Lodge replaced temporary deputy, Rod Clarke, who had stood in for departed bassist, Clint Warwick, at the same time.

After beginning by singing the old Blues inspired repertoire of The Moodies 1964-1965 era, Hayward's initial artistic contribution to The Moody Blues was his song, “Fly Me High,” which was a Decca single early in 1967. This song failed to chart but gave the revised band a new sound and direction, being more of an original contemporary track than the R&B sound they had been largely producing up to that point.

Hayward's driving rocker, “Leave This Man Alone,” was then used as “B” side to the next Moodies single on Decca, backing Mike Pinder's “Love And Beauty” (1967), the first Moodies record to feature the mellotron.

Hayward's and Lodge's integration into the Moody Blues along with Pinder's use of the Mellotron sparked greater commercial success and recognition for the band, transforming them into one of pop music's biggest-selling acts. Hayward says of Pinder, "Mike and the Mellotron made my songs work."

The 1967 album, Days of Future Passed, one of the first and most influential symphonic rock albums, spawned the Hayward-penned singles, "Tuesday Afternoon" and "Nights in White Satin.”

The latter record went on to sell over two million copies, charting three times in the UK (1967, 1972, 1979) and has been recorded by many other recording artists.

Hayward became the group's main onstage figurehead over the 1967-1974 period, the most prolific songwriter and composer of several big singles hits for the band.

The Moody Blues, with Hayward, Lodge and original drummer, Graeme Edge, continue to tour extensively and in a recent BBC World Service interview, Hayward and Lodge made it clear they have no plans to stop working, regarding it as "a privilege" to still be working in the music industry.

Here, Hayward and John Lodge perform “Nights in White Satin.”

Cliff Richard is 83 years old today.

A British pop singer, musician, performer, actor and philanthropist, Richard is the third biggest selling singles artist of all time in the United Kingdom, with total sales of over 21 million in the UK and has reportedly sold an estimated 250 million records worldwide.

With his backing group The Shadows, Richard, originally positioned as a rebellious rock and roll singer in the style of Little Richard and Elvis Presley, dominated the British popular music scene in the pre-Beatles period of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

His 1958 hit single, "Move It," is often described as Britain's first authentic rock and roll song, and John Lennon once claimed that "before Cliff and the Shadows, there had been nothing worth listening to in British music."

Increased focus on his Christian faith and subsequent softening of his music later led to a more middle of the road pop image, sometimes venturing into gospel music.

Over a 50-plus year career, Richard has become a fixture of the British entertainment world, amassing many gold and platinum discs and awards, including three Brit awards and two Ivor Novello awards.

He has had more than 130 singles, albums and EPs make the UK Top 20, more than any other artist and holds the record (with Elvis Presley) as the only act to make the UK singles charts in all of its first six decades (1950s–2000s).

Richard has never achieved the same impact in the United States despite eight U.S. Top 40 singles, including the million-selling "Devil Woman" and "We Don't Talk Anymore,” the latter becoming the first to reach the Hot 100's Top 40 in the 1980s by a singer who had been in the Top 40 in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

Here, Richard performs “Devil Woman.”

Roger Moore was born 96 years old today.

The English actor was best known for his role as the British secret agent, James Bond, in the film series between 1973 and 1985, and also as Simon Templar in The Saint, between 1962 and 1969.

At 18 years old, Moore was commissioned as an officer in the Royal Army Service Corps, commanding a small depot in West Germany.

He later transferred to the entertainment branch (under luminaries such as Spike Milligan), and immediately prior to his national service, there was a brief stint at RADA (the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), during which his fees were paid by film director Brian Desmond Hurst, who also used Moore as an extra in his film, Trottie True.

Moore was a classmate at RADA with his future Bond colleague, Lois Maxwell, the original Miss Moneypenny. The young Moore first appeared in films during the mid to late-1940s, as an extra. Moore's film idol as a child was Stewart Granger.

It was only after Sean Connery had declared that he would not play Bond any longer that Moore became aware that he might be a contender for the role. But after George Lazenby was cast instead and then Sean Connery played Bond again, he didn't consider the possibility until it seemed abundantly clear that Connery had in fact stepped down as Bond for good.

At that point he was indeed approached and accepted the producer's offer in August 1972. Moore says in his autobiography that he had to cut his hair and lose weight, but although he resented that, he was finally cast as James Bond in Live and Let Die (1973).

Moore played Bond in Live and Let Die (1973); The Man with the Golden Gun (1974); The Spy Who Loved Me (1977); Moonraker (1979); For Your Eyes Only (1981); Octopussy (1983) and A View to a Kill (1985).

Moore is the longest-serving James Bond actor, having spent twelve years in the role (from his debut in 1973 to his retirement from the role in 1985), and having made seven official films in a row.

He is also the oldest actor to play Bond. He was 45 when he started, and 58 when he announced his retirement on December 3, 1985.

James Bond was different during this era because times had changed and the scripts were different. Authors like George MacDonald Fraser provided scenarios in which 007 was a kind of seasoned, debonair playboy who would always have a trick or gadget in stock when he needed it. This was designed to serve the contemporary taste.

In 2004, Moore was voted “Best Bond” in an Academy Awards poll and won with a large 62 percent of votes in late 2008.

Moore died in Switzerland on May 23, 2017 from cancer in his liver and lungs. He died in his home in Crans-Montana in the presence of his family.

Here, Moore delivers his “a woman” line to Dr. Goodhead in Moonraker.

e.e. Cummings

Photo by Marion Morehouse

e.e. Cummings, American poet, painter, essayist, author and playwright, was born 129 years ago today.

Cummings’ body of work encompasses approximately 2,900 poems, two autobiographical novels, four plays and several essays, as well as numerous drawings and paintings. He is remembered as a preeminent voice of 20th century poetry.

Born into a Unitarian family, Cummings exhibited transcendental leanings his entire life. As he grew in maturity and age, Cummings moved more toward an "I, Thou" relationship with God.

His journals are replete with references to “le bon Dieu” as well as prayers for inspiration in his poetry and artwork (such as “Bon Dieu! may I some day do something truly great. amen.”).

Cummings "also prayed for strength to be his essential self ('may I be I is the only prayer—not may I be great or good or beautiful or wise or strong'), and for relief of spirit in times of depression ('almighty God! I thank thee for my soul; and may I never die spiritually into a mere mind through disease of loneliness')."

Cummings died of a stroke on September 3, 1962, at the age of 67 in North Conway, New Hampshire at a hospital.

Here, Laurence Fishburne recites e.e. Cummings’ “Freedom Is a Breakfast Food” on Craig Ferguson’s show in 2009.

Natalie Maines is 49 years old today.

Maines is a singer-songwriter and activist who achieved success as the lead vocalist for the female alternative country band, The Chicks (formerly the Dixie Chicks).

Born in Lubbock, Texas, Maines considers herself a rebel who "loved not thinking in the way I knew the majority of people thought."

In 1995, after leaving Berklee College of Music, Maines was recruited by the Chicks to replace their lead singer, Laura Lynch. With Maines as lead vocalist, the band earned great acclaim and many awards.

On the eve of the Iraq invasion, while in concert in London for the 2003 Top of the World Tour, Maines commented that the Chicks were "ashamed the President of the United States is from Texas."

Negative public reaction in the United States to this comment resulted in boycotts by country music radio stations and death threats.

Muhammad Ali

Great personal story on Charlie Moore--how one act of kindness has the power to transform another person’s entire life.