New Yorker writer Joseph Mitchell was born 115 years ago today

Joseph Mitchell at the South Seaport, New York City

Photo by Mario Ruiz

Joseph Mitchell, writer for the New Yorker, was born 115 years ago today.

Mitchell is known for his carefully written portraits of eccentrics and people on the fringes of society — especially in and around New York City.

Born on his maternal grandparents' farm near Fairmont, North Carolina, Mitchell was the son of Averette Nance and Elizabeth A. Parker Mitchell. The family business was cotton and tobacco trading, and family money helped to support Mitchell throughout his life.

At 21, Mitchell came to New York City in 1929 with the ambition of becoming a political reporter. He worked for such newspapers as The World, the New York Herald Tribune and the New York World-Telegram, at first covering crime and then doing interviews, profiles and character sketches.

In 1931, he took a brief break from journalism to work on a freighter that sailed to Leningrad and brought back pulp logs to New York City. He returned to journalism after this interlude and continued to write for New York newspapers until he was hired by St. Clair McKelway at The New Yorker in 1938. He remained with the magazine until his death in 1996.

His book, Up in the Old Hotel, collects the best of his writing for The New Yorker, and his earlier book, My Ears Are Bent, collects the best of his early journalistic writing, which he omitted from Up in the Old Hotel.

Mitchell's last book was his empathetic account of the the Greenwich Village street character and self-proclaimed historian, Joe Gould. Gould’s extravagantly disguised case of writer's block was published as, Joe Gould's Secret, in 1964. Many of Mitchell's admirers agree that this last book sadly presaged the last decades of Mitchell's own life.

From 1964 until his death in 1996, Mitchell would go to work at his office on a daily basis, but he never published anything significant again. In a remembrance of Mitchell printed in the June 10, 1996, issue of The New Yorker, his colleague Roger Angell wrote:

"Each morning, he stepped out of the elevator with a preoccupied air, nodded wordlessly if you were just coming down the hall, and closed himself in his office. He emerged at lunchtime, always wearing his natty brown fedora (in summer, a straw one) and a tan raincoat; an hour and a half later, he reversed the process, again closing the door.

“Not much typing was heard from within, and people who called on Joe reported that his desktop was empty of everything but paper and pencils. When the end of the day came, he went home. Sometimes, in the evening elevator, I heard him emit a small sigh, but he never complained, never explained."

Perhaps an explanation does emerge, however, in a remark that Mitchell made to Washington Post writer David Streitfeld (quoted here from Newsday, August 27, 1992):

"You pick someone so close that, in fact, you are writing about yourself. Joe Gould had to leave home because he didn't fit in, the same way I had to leave home because I didn't fit in. Talking to Joe Gould all those years he became me in a way, if you see what I mean."

Joseph Mitchell served on the board of directors of the Gypsy Lore Society, was one of the founders of the South Street Seaport Museum, was involved with the Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture and served five years on the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

In August, 1937, he placed third in a clam-eating tournament on Block Island by eating 84 cherrystone clams.

He died of cancer in 1996 at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in Manhattan at the age of 87.

In 2008, The Library of America selected Mitchell’s story, "Execution," for inclusion in its two-century retrospective of American True Crime.

The February 11, 2013 edition of The New Yorker includes a previously unpublished piece of Mitchell's entitled, "Street Life: Becoming Part of the City."

“McSorley's Bar,” 1912

Painting by John Sloan

Joseph Mitchell gave a new life to McSorley’s saloon, which is still operating in New York City.

In 1940, Mitchell visited the saloon at 15 East 7th Street. He wrote a watershed article, "The Old House at Home" for the New Yorker.

A new life began for the old saloon. Mitchell's articles are compiled in a book, entitled "McSorley's Wonderful Saloon."

In 1943, Life Magazine did a feature photographic article on "McSorley's Wonderful Saloon."

Photo by Chris Pizzello

Norman Lear, television writer and producer, is 101 years old today.

Lear produced such 1970s sitcoms as All in the Family, Sanford and Son, One Day at a Time, The Jeffersons, Good Times and Maude. As a political activist, he founded the advocacy organization People for the American Way in 1981 and has supported First Amendment rights and progressive causes.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Lear is the son of Jeanette and Herman Lear, a traveling salesman. He has a younger sister, Claire Brown. When he was nine years old, Lear’s father went to prison for selling fake bonds.

Lear thought of his father as a "rascal" and said that the character of Archie Bunker was in part inspired by his father, while the character of Edith Bunker was in part inspired by his mother.

Lear graduated from Weaver High School in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1940 and subsequently attended Emerson College in Boston, but dropped out in 1942 to join the United States Army Air Forces.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, during World War II, Lear enlisted in September, 1942, serving in the Mediterranean Theater as a radio operator/gunner on Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers with the 772nd Bombardment Squadron, 463rd Bombardment Group (Heavy) of the Fifteenth Air Force. He flew 52 combat missions, for which he was awarded the Air Medal with four Oak Leaf Clusters. Lear was discharged from the Army in 1945. He moved to Los Angeles, where he had a first cousin, Elaine, who was married to a man named Ed Simmons, who wanted to be a comedy writer.

Simmons and Lear teamed up to sell home furnishings door-to-door for a company called The Gans Brothers and then sold family photos door-to-door, again with Simmons. Throughout the 1950s, Lear partnered with Simmons, and they turned out comedy sketches for television appearances of Martin and Lewis, Rowan and Martin and others.

Starting out as a comedy writer, then a film director (he wrote and produced the 1967 film, Divorce American Style, and directed the 1971 film, Cold Turkey, both starring Dick Van Dyke), Lear tried to sell a concept for a sitcom about a blue-collar American family to ABC. They rejected the show after two pilots were filmed.

After a third pilot was shot, CBS picked up the show, known as All in the Family. It premiered January 12, 1971, to disappointing ratings, but it took home several Emmy Awards that year, including Outstanding Comedy Series. The show did very well in summer reruns, and flourished in the 1971–72 season, becoming the top-rated show on television for the next five years.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton awarded the National Medal of Arts to Lear, noting, "Norman Lear has held up a mirror to American society and changed the way we look at it." In addition to his success as a TV producer and businessman, Lear is an outspoken supporter of First Amendment and liberal causes.

The only time that he did not support the Democratic candidate for President was in 1980. He voted for John Anderson because he considered the Carter administration to be "a complete disaster.”

In 1981, Lear founded People For the American Way (PFAW), a progressive advocacy organization. PFAW ran several advertising campaigns opposing the interjection of religion in politics.

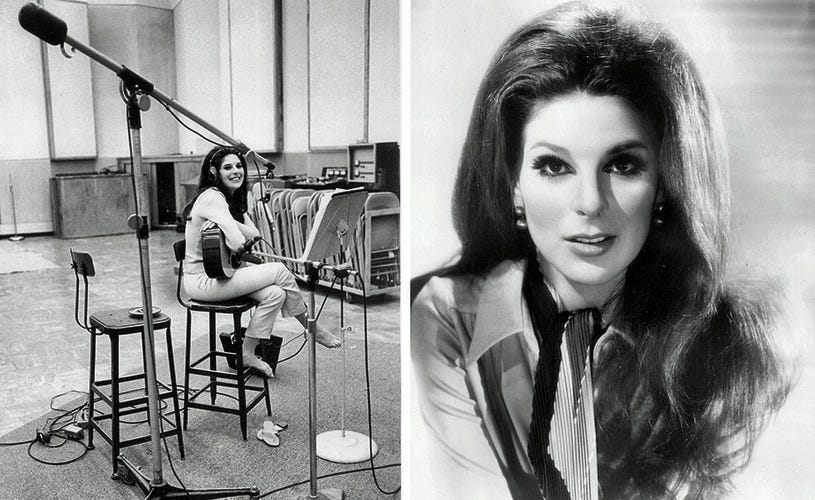

Bobbie Gentry is 81 years old today.

Born as Roberta Lee Streeter, Gentry is a singer-songwriter notable as one of the first female country artists to compose and produce her own material. Her songs typically drew on her Mississippi roots to compose vignettes of the Southern United States.

Gentry rose to international fame with her intriguing Southern Gothic narrative, "Ode to Billie Joe," in 1967. The track spent four weeks as the #1 pop song in the United States.

Gentry charted eleven singles on the Billboard Hot 100 and four singles on the United Kingdom Top 40. After her first albums, she had a successful run of variety shows on the Las Vegas Strip. She lost interest in performing in the late 1970s, and since has lived privately in Los Angeles.

Born in Chickasaw County, Mississippi, Gentry is an only child to Robert and Ruby (Bullington) Streeter. Her parents divorced shortly after her birth, and her mother moved to California. She was raised on her grandparents' farm in Chickasaw County.

Her grandmother traded one of the family's milk cows for a neighbor's piano, and seven-year-old Bobbie composed her first song, "My Dog Sergeant Is a Good Dog." She attended school in Greenwood, Mississippi, and began teaching herself to play the guitar, bass, banjo and vibes.

She moved to Arcadia, California at age 13 to live with her mother. Gentry graduated from Palm Valley School in 1960. She chose her stage name from the 1952 film, Ruby Gentry, about a heroine born into poverty but determined to make a success of her life.

She began performing at local country clubs, and encouraged by Bob Hope, she performed in a revue at Les Folies Bergeres nightclub of Las Vegas. Gentry then moved to Los Angeles to enter UCLA as a philosophy major. She supported herself in clerical jobs, occasionally performing at nightclubs.

She later transferred to the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music to develop her composition and performing skills. In 1964, she made her recording debut in two duets — "Requiem for Love" and "Stranger in the Mirror" with rockabilly singer Jody Reynolds. She continued performing in nightclubs until Capitol Records heard a demo she had recorded in 1967.

In 1967, Gentry produced her first single, the country rock "Mississippi Delta." It was the flipside to "Ode to Billie Joe." With its sparse sound and controversial lyrics, it started to receive airplay in the U.S. Capitol's shortened version added to the song's mystery.

Questions arose among the listeners: what did Billie Joe and his girlfriend throw off the Tallahatchie Bridge and why did Billie Joe commit suicide? The track topped the Billboard Hot 100 for four weeks in August, 1967 and placed #4 in the year-end chart. The single hit #8 on Billboard Black Singles and #13 in the UK Top 40 and sold over three million copies all over the world.

On May 14, 2012, BBC Radio 2 in the UK broadcast a documentary entitled “Whatever Happened to Bobbie Gentry?” It was narrated by country music artist Rosanne Cash.

Gentry has been married three times. Her first marriage was to casino magnate Bill Harrah on December 18, 1969 (he was 58 and she was 25); they were granted a divorce on April 16, 1970, only five months later. She married a businessman named Thomas R. Toutant on August 17, 1976, and again was divorced on August 1, 1978. She married singer and comedian Jim Stafford on October 15, 1978; they divorced just short of one year later, after the birth of their son Tyler Gentry Stafford. She has not since remarried.

When her long-time producer Kelly Gordon fell ill with lung cancer, Gentry took him to her grounds and cared for him until he died in 1981.

From 1968 until 1987, Gentry had partial ownership of the Phoenix Suns.

In a 2016 article, a Washington Post reporter indicated that she currently lives a private life in a gated community in suburban Memphis, about a two-hour drive from the site of the Tallahatchie River bridge that made her famous.

Here, Gentry performs “Ode To Billie Joe” on the Smothers Brothers television show.

In this photograph from the November 10, 1967 issue of Life magazine, Bobbie Gentry strolls across the original Tallahatchie Bridge in Money, Mississippi.

The bridge collapsed in June, 1972. It has since been replaced.

When Herman Raucher met Gentry in preparation for writing a novel and screenplay based on Ode to Billie Joe, Gentry confessed that she had no idea why Billie Joe killed himself. Gentry has, however, commented on the song, saying that its real theme was indifference:

“Those questions are of secondary importance in my mind,” she said. “The story of Billie Joe has two more interesting underlying themes. First, the illustration of a group of peoples' reactions to the life and death of Billie Joe, and its subsequent effect on their lives, is made.

“Second, the obvious gap between the girl and her mother is shown when both women experience a common loss (first Billie Joe, and later, Papa), and yet Mama and the girl are unable to recognize their mutual loss or share their grief.”

Guy and Candie Carawan, Highlander Center, Tennessee

Photo by Frank Beacham

Guy Carawan, folk musician and musicologist, was born 96 years ago today.

Carawan served as music director and song leader for the Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tennessee. He was a legend in the civil rights movement.

Carawan introduced the protest song "We Shall Overcome" to the American Civil Rights Movement, by teaching it to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1960. He also taught it to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

A union organizing song based on a black spiritual, it had been a favorite of Zilphia Horton, the wife of the founder of the Highlander Folk School. Carawan reintroduced it at the school when he became its new music director in 1959. The song is copyrighted in the name of Horton, Frank Hamilton, Carawan and Pete Seeger.

Carawan sang and played banjo, guitar and hammered dulcimer. He frequently performed and recorded with his wife, singer Candie Carawan. Occasionally he was accompanied by their son, Evan Carawan, who plays mandolin and hammered dulcimer. Carawan lived in New Market, near the Highlander Center.

Born in California in 1927 to Southern parents, Carawan’s mother, from Charleston, South Carolina, was the resident poet at Winthrop College (now Winthrop University) in Rock Hill, South Carolina. His father, a veteran of World War I from North Carolina, worked as an asbestos contractor.

He earned a bachelor's degree in mathematics from Occidental College in 1949 and a master's degree in sociology from UCLA. Through his friend, Frank Hamilton, Carawan was introduced to musicians in the People's Songs network, including Pete Seeger and The Weavers.

Moving to New York City, he became involved with the American folk music revival in Greenwich Village in the 1950s. He also traveled abroad, visiting England, attending a World Festival of Youth and Students in the Soviet Union in 1957 and continuing on to the People's Republic of China.

Carawan first visited the Highlander Folk School in 1953, with singers Ramblin' Jack Elliot and Frank Hamilton. At the recommendation of Pete Seeger, he returned in 1959 as a volunteer, taking charge of the music program pioneered by Zilphia Horton, who had died in an accident in 1956.

When college students in Greensboro, N.C., began the lunch-counter sit-in movement on Feb 1, 1960, Highlander's youth program took on a new urgency. Highlander's seventh annual college workshop took place on the first weekend in April, with 83 students from 20 colleges attending. As part of a talent show and dance, Carawan taught the students the song "We Shall Overcome."

Two weeks later, on April 15, two hundred students assembled in Raleigh, NC, for a three-day conference at Shaw University. Called by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to develop a youth wing, the students instead organized the independent Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

They invited Carawan to lead the singing, and he closed the first evening with "We Shall Overcome." The audience stood, linked hands and sang — and went away inspired, carrying the song to meetings and demonstrations across the South.

Movement leader Rev. C. T. Vivian, a lieutenant of Martin Luther King reminisced: “I don’t think we had ever thought of spirituals as movement material. When the movement came up, we couldn’t apply them. The concept has to be there. It wasn’t just to have the music, but to take the music out of our past and apply it to the new situation, to change it so it really fit.... The first time I remember any change in our songs was when Guy came down from Highlander.

“Here he was with this guitar and tall thin frame, leaning forward and patting that foot. I remember James Bevel and I looked across at each other and smiled. Guy had taken this song, "Follow the Drinking Gourd" – I didn't know the song, but he gave some background on it and boom – that began to make sense. And, little by little, spiritual after spiritual began to appear with new words and changes: “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize, Hold On” or “I’m Going to Sit at the Welcome Table.” Once we had seen it done, we could begin to do it.”

At Highlander's April workshop, Carawan had met Candie Anderson, an exchange student at Fisk University in Nashville, from Pomona College in California, who was one of the first white students involved in the sit-in movement. They were married in March, 1961.

Carawan died on May 2, 2015 at age 87.

A lion named “Jackie” was used to pose for Leo in 1928

Leo the Lion is the mascot for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and one of its predecessors, Goldwyn Pictures. Leo was featured in the studio's production logo, which was created by the Paramount Studios art director, Lionel S. Reiss.

Since 1917 (and when the studio was formed by the merger of Samuel Goldwyn's studio with Marcus Loew's Metro Pictures and Louis B. Mayer's company in 1924), there have been seven different lions used for the MGM logo.

Though MGM has referred to all of the lions used in their trademark as "Leo the Lion,” only the current lion, in use since 1957, was actually named "Leo.”

Heat Wave

Painting by Ron Schwerin