Musician and actress Ronee Blakley is 78 years old today

Ronee Blakley performs on Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Review

Ronee Blakley is 78 years old today.

Although an accomplished singer, songwriter, composer, producer and director, Blakley is perhaps best known as an actress. Her most famous role was as the fictional country superstar, Barbara Jean, in Robert Altman's 1975 film, Nashville, for which she won a National Board of Review Award for Best Supporting Actress and was nominated for an Academy Award.

She also had a notable role in, A Nightmare on Elm Street, in 1984.

Born in Nampa, Idaho, Blakley studied at Mills College, Stanford University and went to New York to attend Juilliard for post-graduate work. She began in New York improvising vocally with Moog synthesizers in Carnegie Hall to music by Gershon Kingsley.

Her first soundtrack was composed for the 20th Century Fox film, Welcome Home Soldier Boys, and earned her a spot in Who's Who in America. In 1972, the folk-rock album, Ronee Blakley, debuted on Elektra Records and featured Blakley’s original songs, arranged and accompanied by herself on her piano.

The song, “Bluebird,” featured a duet with Linda Ronstadt. Blakley's songs were published by her own company, Sawtooth Music. Her second album, Welcome, was released on Warner Brothers in 1975. It was produced by Jerry Wexler and recorded at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Alabama. The Los Angeles Herald Examiner called it a "near perfect album."

That same year, Blakley appeared in what may be her most widely known performance in Nashville. Her character, Barbara Jean, was purported to be modeled after country star, Loretta Lynn. In Nashville, Blakley performed her own songs in character, including "Tapedeck In His Tractor," "Dues" and "My Idaho Home."

In her review for The New Yorker, film critic Pauline Kael wrote: “This is Ronee Blakley’s first movie, and she puts most movie hysteria to shame. She achieves her gifts so simply, I wasn’t surprised when somebody sitting beside me started to cry. Perhaps, for the first time on the screen, one gets the sense of an artist being destroyed by her gifts.”

Blakley was nominated for an Academy Award in the category Best Supporting Actress along with Lily Tomlin, who was also nominated in the same category. She was also nominated for a Grammy, a Golden Globe and a British Academy award, and won the National Board of Review award for Best Supporting Actress. She was featured on the covers of Newsweek, American Cinematographer and Andy Warhol's Interview Magazine.

Blakley toured as backup singer to Bob Dylan in the Rolling Thunder Revue, the caravan Dylan put together to tour after his album, "Desire.” She appears on the live albums from that tour "Hard Rain" and "The Bootleg Series Vol. 5: Bob Dylan Live 1975, The Rolling Thunder Revue.”

She also recorded with Leonard Cohen and Hoyt Axton.

Here is Blakley performs “My Idaho Home” in Robert Altman’s Nashville, 1975.

Wynonie Harris with fans at a Chicago nightclub

Wynonie Harris was born 108 years ago today.

Harris was a blues shouter and rhythm and blues singer of upbeat songs, featuring humorous, often ribald lyrics. With fifteen Top 10 hits between 1946 and 1952, he is generally considered one of rock and roll's forerunners, influencing Elvis Presley among others. He was the subject of a 1994 biography by Tony Collins.

Harris' mother, Mallie Hood Anderson, was fifteen and unmarried at the time of his birth. Harris' paternity is uncertain. In 1931, at age 16, Harris dropped out of high school in North Omaha, Nebraska. The following year his first child, daughter Micky, was born to Naomi Henderson. Ten months later, Harris' second child, son Wesley, was born to Laura Devereaux. Both children were raised by their mothers.

With dance partner, Velda Shannon, Harris formed a dance team in the early 1930s. The team performed around North Omaha's flourishing entertainment community, and by 1934 they were a regular attraction at the Ritz Theatre.

It was not until 1935, however, that Harris was able to earn his living as an entertainer. While performing at Jim Bell's new Harlem nightclub with Shannon, Harris began to sing the blues. He also began traveling frequently to Kansas City, where he paid close attention to the blues shouters including Jimmy Rushing and Big Joe Turner.

Harris became a local celebrity in Omaha during the depths of the Great Depression in 1935. His break in Los Angeles was at a nightclub owned by Curtis Mosby. It was here that Harris became known as, "Mr. Blues."

Due to the 1942-44 musicians' strike, Harris was unable to pursue a recording career. Instead, he relied on personal appearances. Performing almost continuously, he appeared at the Rhumboogie Club in Chicago in late 1943.

Harris was spotted by Lucky Millinder, who asked him to join his band's tour. He joined on March 24, 1944, while the band was in the middle of a week-long residency at the Regal in Chicago. They moved on to New York, where on April 7 Harris took the stage with Millinder's band for his debut at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem.

It was during this performance that Harris first publicly performed, "Who Threw the Whiskey in the Well," a song recorded two years earlier by Doc Wheeler's Sunset Orchestra. After the band's stint at the Apollo, they moved on to their regular residency at the Savoy Ballroom, also in Harlem. Here, Preston Love, Harris' childhood friend, joined Millinder's band replacing alto saxophonist, Tab Smith.

On May 26, 1944, Harris made his recording debut with Lucky Millinder and His Orchestra. Entering a recording studio for the first time, Harris sang on two of the five cuts that day, "Hurry, Hurry" and "Who Threw the Whiskey in the Well,” for the Decca label. Although lessening, the shellac embargo had not yet been removed, and release of the record was delayed.

Harris' success and popularity grew as Millinder's band toured the country. He and Millinder, however, had a falling out over money. In September, 1945, while playing in San Antonio, Texas, Harris quit Millinder's band.

Three weeks later, upon hearing of Harris' separation from the band, a Houston, Texas promoter refused to allow Millinder's band to perform. Millinder called Harris and agreed to pay Harris' asking price of $100 a night. The promoter re-instated the date, but it was the final time Harris and Millinder worked together. Bull Moose Jackson replaced Harris as the vocalist in the band.

In April, 1945, a year after the song was recorded, Decca released "Who Threw the Whiskey in the Well.” It became the group's biggest hit. The song went to #1 on the Billboard R&B chart on July 14 and stayed there for eight weeks.

It remained on the charts for almost five months, also becoming popular with white audiences, an unusual feat for black musicians of that era. In California, the success of the song opened doors for Harris.

Since the contract with Decca was with Millinder (meaning Harris was a free agent), Harris could choose from the recording contracts with which he was presented.

As a solo act, Harris went on to record sessions for Apollo, Bullet and Aladdin. His greatest success came when he signed for Syd Nathan's King label, where he enjoyed a series of hits on the Race Music and R&B chart in the United States the late 1940s and early 1950s. These included a 1948 cover of Roy Brown's "Good Rocking Tonight,” "Good Morning Judge" and "All She Wants to Do Is Rock.”

On June 14, 1969, at aged 53, Harris died of esophageal cancer at the USC Medical Center Hospital in Los Angeles.

Here, Harris performs “Rock Mr. Blues” in 1950.

The Wizard of Oz is celebrating its 83rd anniversary today, but the classic film very nearly ended up a disastrous footnote in the history of Hollywood.

The production was a mess, cycling through directors and screenwriters. Victor Fleming, the sole credited director, replaced Richard Thorpe less than two weeks into filming, and shot most of the scenes before sprinting off to save “Gone With the Wind.” King Vidor finished the job.

Cast members were injured during filming: Margaret Hamilton, who played the terrifying Wicked Witch of the West, was severely burned; and Buddy Ebsen, cast as the Tin Man, was poisoned by his makeup. (Jack Haley took over the role.) The movie went over budget and wasn’t a hit on its initial release.

Today, The Wizard of Oz endures as a cultural icon, thanks in large part to TV syndication from the late 1950s; Judy Garland’s signature performance of “Over the Rainbow;” and those coveted ruby slippers.

Thanks New York Times!

George Crum and his accidental invention

Potato chips were accidentally invented 170 years ago this summer in Saratoga Springs, New York by an irascible chef trying to get even with a customer.

The chef, George Crum, is widely credited with inventing potato chips during the summer of 1853 when a customer at Moon’s Lake House sent back his fried potatoes because they were thick and soggy.

Crum wasn’t pleased by this, so he thinly sliced the potatoes, fried them in grease and showered them with salt. The “fries” were too thin to eat with a fork and Crum hoped to annoy the fussy customer.

To his surprise, the formerly disgruntled diner loved the “potato crunches,” as Crum originally called them. Potato chips were born. They quickly became popular at the restaurant, and were originally known as Saratoga Chips.

Crum was born in upstate New York to a black father and a Native American mother, and before becoming a chef, he worked as a guide in the Adirondacks. He later opened his own successful restaurant. A basket of potato chips was on every table and were available for takeout.

Crum died in 1914 and never patented his creation. But his culinary contribution did not go unrecognized: In 1976, he was honored with a plaque near Moon’s Lake House.

Thanks New York Times!

Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup was born 118 years ago today.

A Delta blues singer, songwriter and guitarist, Crudup wrote songs such as "That's All Right" (1946), "My Baby Left Me" and "So Glad You're Mine," later covered by Elvis Presley and dozens of other artists.

Born in Forest, Mississippi, for a time Crudup lived and worked throughout the South and Midwest as a migrant worker. He and his family returned to Mississippi in 1926. He sang gospel, then began his career as a blues singer around Clarksdale, Mississippi.

As a member of the Harmonizing Four, Crudup visited Chicago in 1939. He stayed in Chicago to work as a solo musician, but barely made a living as a street singer. Lester Melrose, a record producer, allegedly found him while he was living in a packing crate, introduced him to Tampa Red and signed him to a recording contract with RCA Victor's Bluebird label.

Crudup recorded with RCA in the late 1940s and with Ace Records, Checker Records and Trumpet Records in the early 1950s. He toured black clubs in the South, including with Sonny Boy Williamson II and Elmore James. He also recorded under the names Elmer James and Percy Lee Crudup. His songs "Mean Old 'Frisco Blues," "Who's Been Foolin' You" and "That's All Right" were popular in the South.

Crudup stopped recording in the 1950s, because of further battles over royalties. His last Chicago session was in 1951. His 1952-54 recording sessions for Victor were done at WGST, a radio station in Atlanta. He returned to recording with Fire Records and Delmark Records and touring in 1965.

Sometimes labeled as "The Father of Rock and Roll," he accepted this title with some bemusement. Throughout this time, Crudup worked as a laborer to augment the non-existent royalties and the small wages he received as a singer. He returned to Mississippi after a dispute with Melrose over royalties, then went into bootlegging, and later moved to Virginia where he had lived and worked as a musician and laborer.

In the early 1970s, two local Virginia activists, Celia Santiago and Margaret Carter, assisted him in an attempt to gain royalties he felt he was due. They had little success. While he lived in relative poverty as a field laborer, he occasionally sang and supplied moonshine to a number of drinking establishments, including one called The Dew-Drop Inn in Northampton County.

He did this for some time prior to his death from complications of heart disease and diabetes. On a 1970 trip to the United Kingdom, he recorded "Roebuck Man" with local musicians. His last professional engagements were with Bonnie Raitt.

Crudup died of a heart attack in the Nassawadox hospital in Northampton County, Virginia in March, 1974.

Here, Crudup performs “That’s All Right,” written in 1946.

Howard Zinn, New York City, May 13, 2009

Photo by Frank Beacham

Howard Zinn was born 101 years ago today.

Zinn was an academic historian, author, playwright and social activist. Before and during his tenure as a political science professor at Boston University from 1964-88, he wrote more than 20 books, which included his best-selling and influential, A People's History of the United States.

Zinn wrote extensively about the civil rights and anti-war movements, as well as of the labor history of the United States. His memoir, You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train, was also the title of a 2004 documentary about Zinn's life and work.

Born to a Jewish immigrant family in Brooklyn, Zinn’s father, Eddie Zinn, born in Austria-Hungary, emigrated to the U.S. with his brother Samuel before the outbreak of World War I. Howard's mother, Jenny, emigrated from the Eastern Siberian city of Irkutsk.

Both parents were factory workers with limited education when they met and married, and there were no books or magazines in the series of apartments where they raised their children.

Zinn's parents introduced him to literature by sending 10 cents plus a coupon to the New York Post for each of the 20 volumes of Charles Dickens' collected works. He also studied creative writing at Thomas Jefferson High School in a special program established by poet Elias Lieberman.

Eager to fight fascism, Zinn joined the Army Air Force during World War II and was assigned as a bombardier in the 490th Bombardment Group, bombing targets in Berlin, Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

A U.S. bombardier in April, 1945, Zinn dropped napalm bombs on Royan, a seaside resort in southwestern France. The anti-war stance Zinn developed later was informed, in part, by his experiences.

On a post-doctoral research mission nine years later, Zinn visited the resort near Bordeaux where he interviewed residents, reviewed municipal documents and read wartime newspaper clippings at the local library. In 1966, Zinn returned to Royan after which he gave his fullest account of that research in his book, The Politics of History.

On the ground, Zinn learned that the aerial bombing attacks in which he participated had killed more than 1,000 French civilians as well as some German soldiers hiding near Royan to await the war's end. The events that are described "in all accounts," he found, as "une tragique erreur" that leveled a small but ancient city and "its population that was, at least officially, friend, not foe."

In The Politics of History, Zinn described how the bombing was ordered — three weeks before the war in Europe ended — by military officials who were, in part, motivated more by the desire for their own career advancement than in legitimate military objectives.

He quotes the official history of the U.S. Army Air Forces' brief reference to the Eighth Air Force attack on Royan and also, in the same chapter, to the bombing of Pilsen in what was then Czechoslovakia. The official history stated that the famous Skoda works in Pilsen "received 500 well-placed tons," and that "because of a warning sent out ahead of time the workers were able to escape, except for five persons."

Zinn questioned the justifications for military operations that inflicted massive civilian casualties during the Allied bombing of cities such as Dresden, Royan, Tokyo; and Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II; Hanoi during the War in Vietnam; and Baghdad during the war in Iraq and the civilian casualties during bombings in Afghanistan during the current and nearly decade-old war there.

In his pamphlet, “Hiroshima: Breaking the Silence,” written in 1995, he laid out the case against targeting civilians with aerial bombing.

After World War II, Zinn attended New York University on the GI Bill, graduating with a B.A. in 1951.

At Columbia University, he later earned an M.A. (1952) and a Ph.D. in history with a minor in political science (1958). His masters' thesis examined the Colorado coal strikes of 1914.

In 1964, Zinn accepted a position at Boston University, after writing two books and participating in the Civil Rights movement in the South. His classes in civil liberties were among the most popular at the university with as many as 400 students subscribing each semester to the non-required class. A professor of political science, he taught at Boston University for 24 years and retired in 1988 at age 64.

"He had a deep sense of fairness and justice for the underdog. But he always kept his sense of humor. He was a happy warrior," said Caryl Rivers, journalism professor at Boston University. Rivers and Zinn were among a group of faculty members who in 1979 defended the right of the school's clerical workers to strike and were threatened with dismissal after refusing to cross a picket line.

Zinn came to believe that the point of view expressed in traditional history books was often limited. He wrote a history textbook, A People's History of the United States, to provide other perspectives on American history. The textbook depicts the struggles of Native Americans against European and U.S. conquest and expansion, slaves against slavery, unionists and other workers against capitalists, women against patriarchy, and African-Americans for civil rights.

The book was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1981. In the years since the first edition of A People's History was published in 1980, it has been used as an alternative to standard textbooks in many high school and college history courses, and it is one of the most widely known examples of critical pedagogy.

The New York Times Book Review stated in 2006 that the book "routinely sells more than 100,000 copies a year.” Zinn described himself as "something of an anarchist, something of a socialist. Maybe a democratic socialist.” He suggested looking at socialism in its full historical context as a popular, positive idea that got a bad name from its association with Soviet Communism.

Zinn was swimming in a hotel pool when he died of an apparent heart attack in Santa Monica, California, on January 27, 2010. He was 87.

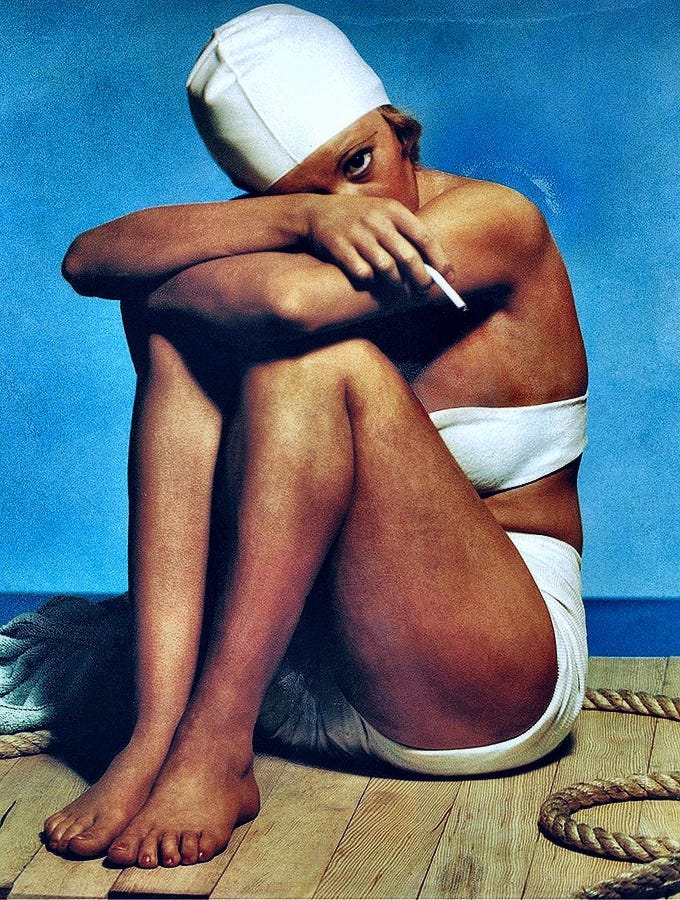

Girl in Bathing Suit, 1936

Photo by Paul Outerbridge, Jr.