James Cagney, stage and film actor, was born 124 years ago today

James Cagney was born 124 years ago today.

Cagney, a stage and film actor, won acclaim and major awards for a wide variety of performances — though he is best remembered for playing tough guys. In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked him eighth among its 50 Greatest American Screen Legends.

In Cagney’s first professional acting performance, he danced and dressed as a woman in the chorus line of the 1919 revue, Every Sailor. He spent several years in vaudeville as a hoofer and comedian, until he got his first major acting part in 1925. He secured several other roles, receiving good notices, before landing the lead in the 1929 play, Penny Arcade.

After rave reviews, Warner Brothers signed Cagney for an initial $500-a-week, three-week film contract to reprise his role. This was quickly extended to a seven-year contract.

Cagney's seventh film, The Public Enemy, became one of the most influential gangster movies of the period. Notable for its famous grapefruit scene, the film thrust Cagney into the spotlight, making him one of Warners' and Hollywood's biggest stars.

In 1938, he received his first Academy Award for Best Actor nomination, for Angels with Dirty Faces, before winning in 1942 for his portrayal of George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy.

He was nominated a third time in 1955 for Love Me or Leave Me. Cagney retired for twenty years in 1961, spending time on his farm, before returning for a part in Ragtime, mainly to aid his recovery from a stroke.

Cagney walked out on Warner Brothers several times over the course of his career, each time coming back on better personal and artistic terms. In 1935, he sued the studio for breach of contract and won. This marked one of the first times an actor had beaten a studio over a contract issue.

He worked for an independent film company for a year while the suit was being settled, and also established his own production company, Cagney Productions, in 1942. He returned to Warner Brothers four years later.

Jack Warner called him "The Professional Againster,” in reference to Cagney’s refusal to be pushed around. Cagney also made numerous morale-boosting troop tours before and during World War II and was president of the Screen Actors Guild for two years.

He died in 1986 at age 86.

Here, Cagney, smashes a grape fruit in Mae Clark’s face in Public Enemy, 1931.

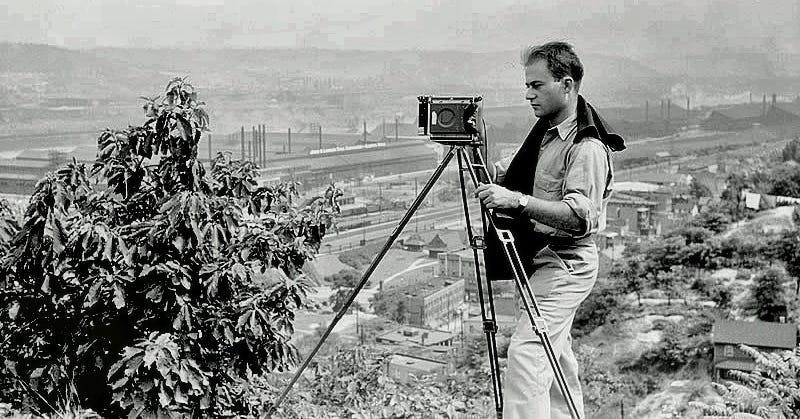

Arthur Rothstein, one of America’s premier photojournalists, was born 108 years ago today.

During a career that spanned five decades, Rothstein provoked, entertained and informed with photographs that ranged from a hometown baseball game to the drama of war, from struggling rural farmers to U.S. Presidents.

Born in New York City and raised in the Bronx, Rothstein was a graduate of Columbia University, where he was a founder of the University Camera Club and photography editor of the Columbian.

Following his graduation from Columbia during the Great Depression, Rothstein was invited to Washington D.C. by one of his professors at Columbia, Roy Stryker. Rothstein had been Stryker's student at Columbia University in the early 1930s. In 1934, as a college senior, Rothstein prepared a set of copy photographs for a picture source book on American agriculture that Stryker and another professor, Rexford Tugwell, were assembling.

The book was never published, but before the year was out, Tugwell was part of FDR's New Deal brain trust. He hired Stryker and Stryker hired Rothstein to set up the darkroom for Stryker's Photo Unit of the Historical Section of the Resettlement Administration (RA), which became the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in 1937. Later, when the country geared up for World War II, the FSA became part of the Office of War Information (OWI).

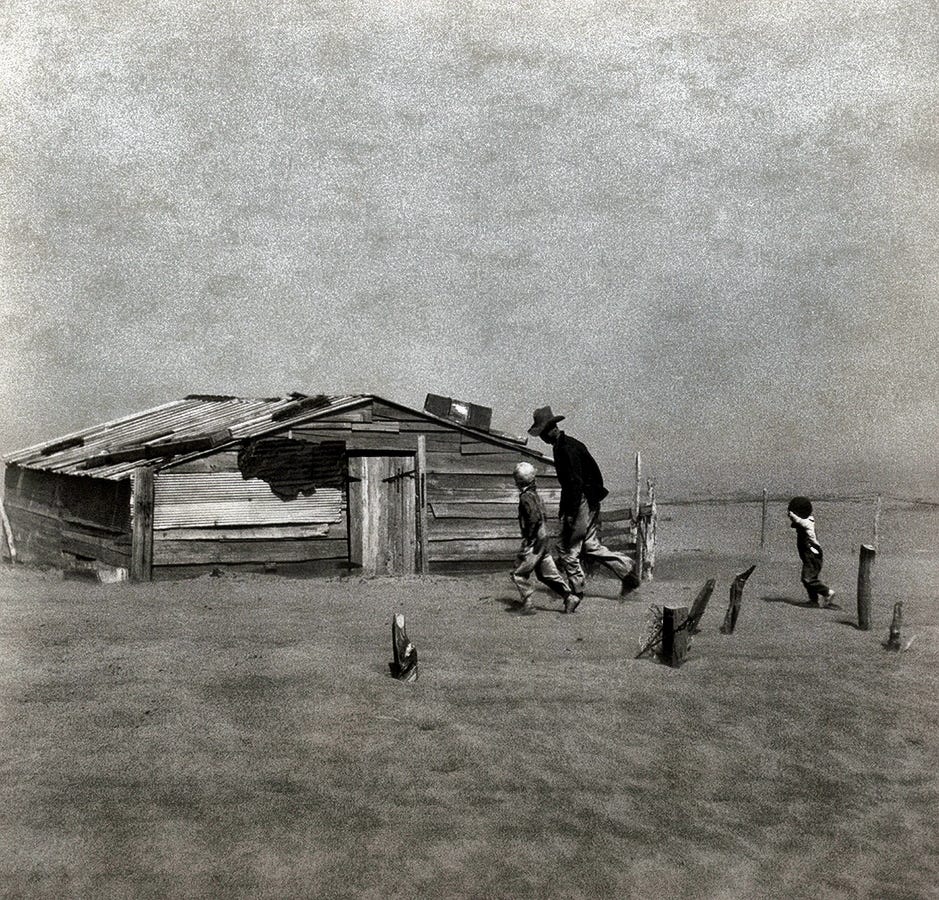

Perhaps Rothstein's most famous photo, and an icon of the Dust Bowl, is the image of a farmer and his two sons during a dust storm in Cimarron County, Oklahoma in 1936. Rothstein became the first photographer sent out by Roy Stryker, the head of the Photo Unit. During the next five years, he shot some of the most significant photographs ever taken of rural and small-town America.

He and other FSA photographers, including Esther Bubley, Marjory Collins, Marion Post Wolcott, Walker Evans, Russell Lee, Gordon Parks, Jack Delano, Charlotte Brooks, John Vachon, Carl Mydans, Dorothea Lange and Ben Shahn, were employed to publicize the living conditions of the rural poor in the United States. The photographs made during Rothstein's five-year stint with the photographic section form a catalog of the agency's initiatives.

His first assignment was to document the lives of some Virginia farmers who were being evicted to make way for the Shenandoah National Park and about to be relocated by the Resettlement Administration, and subsequent trips took him to the Dust Bowl and to cattle ranches in Montana.

The immediate incentive for his February, 1937 assignment came from the interest generated by congressional consideration of farm tenant legislation sponsored in the Senate by John H. Bankhead, a moderate Democrat from Alabama with a strong interest in agriculture.

Enacted in July, the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act gave the agency its new lease on life as the Farm Security Administration. In 1940, Rothstein became a staff photographer for Look magazine, but left shortly thereafter to join the OWI and then the U.S. Army as a photographer in the Signal Corps.

His military assignment took him to the China-Burma-India theatre and he remained in China following his discharge from the military in 1945, working as chief photographer for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. He documented the Great Famine and the plight of displaced survivors of the Holocaust in the Hongkew ghetto of Shanghai.

In 1947, Rothstein rejoined Look as Director of Photography. He remained at Look until 1971, when the magazine ceased publication. Rothstein then joined Parade magazine in 1972 as Director of Photography and remained there until his death.

One of Rothstein’s children is Rob Stoner, the multi-instrumental musician, who was bandleader and bass player for Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Review.

A farmer and his two sons during a dust storm in Cimarron County, Oklahoma, 1936

Photo by Arthur Rothstein

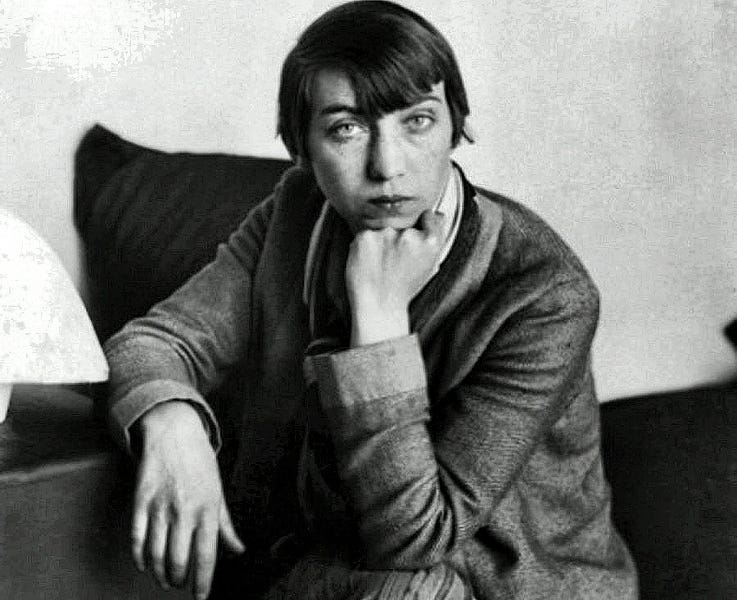

Self portrait of Berenice Abbott, 1928

Berenice Abbott, New York City urban photographer, was born 125 years ago today.

Abbott photographed New York City like few others in the 1930s. She specialized in architecture and urban design. Thousands of her photos are in the online archives of the Museum of the City of New York.

Born in Springfield, Ohio, Abbott was brought up there by her divorced mother. She attended the Ohio State University, but left in early 1918, moving with friends to New York's Greenwich Village. There she was “adopted” by the anarchist, Hippolyte Havel.

She shared an apartment on Greenwich Avenue with several others, including the writer Djuna Barnes, philosopher Kenneth Burke and literary critic, Malcolm Cowley. At first she pursued journalism, but soon became interested in theater and sculpture. In 1919 she nearly died in the influenza pandemic.

Abbott went to Europe in 1921, spending two years studying sculpture in Paris and Berlin. She studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris and the Kunstschule in Berlin.

During this time, she adopted the French spelling of her first name, "Berenice," at the suggestion of Djuna Barnes. In addition to her work in the visual arts, Abbott published poetry in the experimental literary journal transition.

Abbott first became involved with photography in 1923, when Man Ray hired her as a darkroom assistant at his portrait studio in Montparnasse. Later she wrote: "I took to photography like a duck to water. I never wanted to do anything else."

Ray was impressed by her darkroom work and allowed her to use his studio to take her own photographs. In 1926, she exhibited her work in the gallery "Au Sacre du Printemps" and started her own studio on the rue du Bac.

After a short time studying photography in Berlin, she returned to Paris in 1927 and started a second studio, on the rue Servandoni.

Abbott's subjects were people in the artistic and literary worlds, including French nationals (Jean Cocteau), expatriates (James Joyce) and others just passing through the city. According to Sylvia Beach, "To be 'done' by Man Ray or Berenice Abbott meant you rated as somebody."

Abbott's work was exhibited with that of Man Ray, André Kertész and others in Paris, in the "Salon de l'Escalier" (more formally, the Premier Salon Indépendant de la Photographie), and on the staircase of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.

Her portraiture was unusual within exhibitions of modernist photography held in 1928–9 in Brussels and Germany.

In 1925, Man Ray introduced her to Eugène Atget's photographs. She became interested in Atget's work, and managed to persuade him to sit for a portrait in 1927. He died shortly thereafter.

While the government acquired much of Atget's archive — Atget had sold 2,621 negatives in 1920, and his friend and executor André Calmettes sold 2,000 more immediately after his death — Abbott was able to buy the remainder in June, 1928, and quickly started work on its promotion.

An early tangible result was the 1930 book, Atget, photographe de Paris, in which she is described as photo editor. Abbott's work on Atget's behalf would continue until her sale of the archive to the Museum of Modern Art in 1968.

In early 1929, Abbott visited New York City, ostensibly to find an American publisher for Atget's photographs. Upon seeing the city again, however, Abbott immediately saw its photographic potential.

Accordingly, she went back to Paris, closed up her studio and returned to New York in September. Her first photographs of the city were taken with a hand-held Kurt-Bentzin camera, but soon she acquired a Century Universal camera which produced 8 x 10 inch negatives.

Using this large format camera, Abbott photographed New York City with the diligence and attention to detail she had so admired in Eugène Atget. Her work has provided a historical chronicle of many now-destroyed buildings and neighborhoods of Manhattan.

Abbott worked on her New York project independently for six years, unable to get financial support from organizations (such as the Museum of the City of New York), foundations (such as the Guggenheim Foundation) or individuals.

She supported herself with commercial work and teaching at the New School of Social Research beginning in 1933. In 1935, however, Abbott was hired by the Federal Art Project (FAP) as a project supervisor for her "Changing New York" project.

She continued to take the photographs of the city, but she had assistants to help her both in the field and in the office. This arrangement allowed Abbott to devote all her time to producing, printing and exhibiting her photographs.

By the time she resigned from the FAP in 1939, she had produced 305 photographs that were then deposited at the Museum of the City of New York. Abbott's project was primarily a sociological study embedded within modernist aesthetic practices.

She sought to create a broadly inclusive collection of photographs that together suggest a vital interaction between three aspects of urban life: the diverse people of the city, the places they live, work and play, and their daily activities.

It was intended to empower people by making them realize that their environment was a consequence of their collective behavior (and vice versa). Moreover, she avoided the merely pretty in favor of what she described as "fantastic" contrasts between the old and the new, and chose her camera angles and lenses to create compositions that either stabilized a subject (if she approved of it), or destabilized it (if she scorned it).

Abbott's ideas about New York were highly influenced by Lewis Mumford's historical writings from the early 1930s, which divided American history into a series of technological eras. Abbott, like Mumford, was particularly critical of America's "paleotechnic era," which, as he described it, emerged at end of the American Civil War, a development called by other historians the Second Industrial Revolution.

Like Mumford, Abbott was hopeful that, through urban planning efforts (aided by her photographs), Americans would be able to wrest control of their cities from paleotechnic forces, and bring about what Mumford described as a more humane and human-scaled, "neotechnic era."

Abbott's agreement with Mumford can be seen especially in the ways that she photographed buildings that had been constructed in the paleotechnic era — before the advent of urban planning. Most often, buildings from this era appear in Abbott's photographs in compositions that made them look downright menacing.

The film "Berenice Abbott: A View of the 20th Century," which showed 200 of her black and white photographs, suggests that she was a “proud proto-feminist,” someone who was ahead of her time in feminist theory. Before the film was completed she questioned, "The world doesn't like independent women, why, I don't know, but I don't care."

She lived with art critic Elizabeth McCausland for 30 years and is in major lesbian artist archives.

Abbott died on Dec. 9, 1991 at the age of 93.

Jean Cocteau with Gun, 1926

Photo by Berenice Abbott

Billie Holiday and John Coltrane

Two jazz greats died on this day.

In 1967‚ 56 years ago today, jazz saxophonist and composer John Coltrane died from liver cancer at Huntington Hospital in Long Island. He was 40.

One of his biographers, Lewis Porter, has suggested that the cause of Coltrane's illness was hepatitis, although he also attributed the disease to Coltrane's heroin use.

Coltrane's death surprised many in the musical community who were not aware of his condition. Several of his friends said they didn’t know he was that sick at all.

In 1959 — 64 years ago today — Billie Holiday died at age 43 in a New York City hospital from cirrhosis of the liver after years of alcohol abuse.

At the time, she was under arrest for heroin possession with police stationed at the door to her room.

In the final years of her life, she had been progressively swindled out of her earnings and died with 70 cents in the bank.

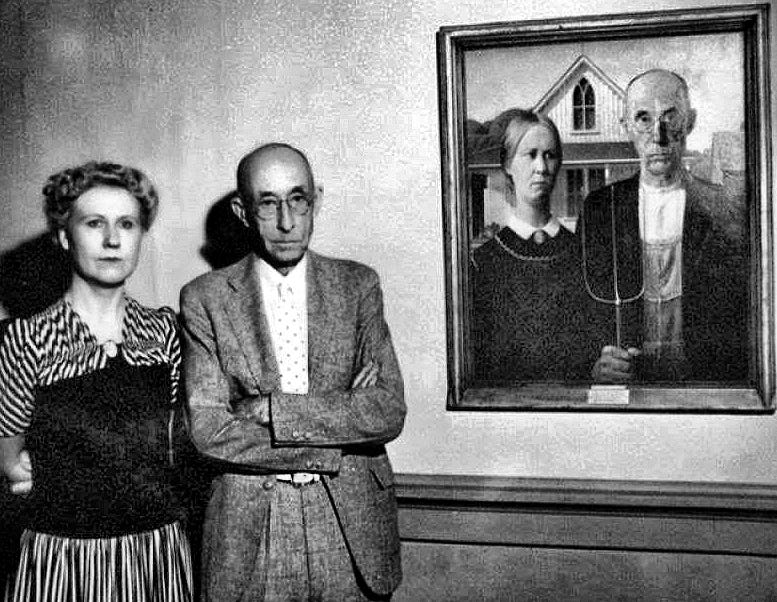

In 1930, Iowa artist Grant Wood painted American Gothic.

The models he used for the painting were his sister, Nan Wood Graham, and his dentist, Byron McKeeby. Here they pose by the original painting. American Gothic is now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Wood's inspiration came from a cottage designed in the Gothic Revival style with a distinctive upper window and a decision to paint the house along with "the kind of people I fancied should live in that house." The painting shows a farmer standing beside his spinster daughter.

The woman is dressed in a colonial print apron evoking 19th century Americana, and the couple are in the traditional roles of men and women, the man's pitchfork symbolizing hard labor, and the flowers over the woman's right shoulder suggesting domesticity.

It is one of the most familiar images in 20th century American art, and one of the most parodied artworks within American popular culture.

Phoebe Snow performs with the Levon Helm Band, Beacon Theatre, New York City, 2009

Photo by Frank Beacham

Phoebe Snow was born 73 years ago today.

Snow was a singer, songwriter and guitarist best known for her chart-topping 1975 hit, "Poetry Man.” She was described by The New York Times as a "contralto grounded in a bluesy growl and capable of sweeping over four octaves."

Born in New York City in 1950, Snow was raised in a musical household in which Delta blues, Broadway show tunes, Dixieland jazz, classical music and folk music recordings were played around the clock.

Her father, Merrill Laub, an exterminator by trade, had an encyclopedic knowledge of American film and theater and was also an avid collector and restorer of antiques. Her mother, Lili, was a dance teacher who had performed with the Martha Graham group.

Snow grew up in Teaneck, New Jersey and graduated from Teaneck High School. She subsequently attended Shimer College in Mount Carroll, Illinois, but did not graduate. As a student, she carried her prized Martin 000-18 acoustic guitar from club to club in Greenwich Village, playing and singing on amateur nights.

Her stage name is a fictional advertising character created in the early 1900s for the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. Phoebe Snow was a young woman who appeared dressed all in white. Also, a DL&W passenger train called the Phoebe Snow ran from Hoboken to Buffalo between 1949 and 1960.

Snow was briefly married to Phil Kearns, and in December, 1975 she gave birth to a severely mentally impaired daughter, Valerie Rose. Snow resolved not to institutionalize Valerie, and cared for her at home until Valerie died on March 18, 2007 at the age of 31.

Snow's efforts to care for Valerie nearly ended her career. She continued to take voice lessons and she studied opera informally. It was at The Bitter End club in 1972 that Denny Cordell, a promotions executive for Shelter Records, was so taken by the singer that he signed her to the label and produced her first recording.

She released an album, Phoebe Snow, in 1974. It featured guest performances by The Persuasions, Zoot Sims, Teddy Wilson, David Bromberg and Dave Mason. Snow's album went on to sell over a million copies in the United States and became one of the most acclaimed recordings of the era.

Phoebe Snow suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on January 19, 2010 and slipped into a coma, enduring bouts of blood clots, pneumonia and congestive heart failure.

She died on April 26, 2011 at age 60 in Edison, New Jersey.

Here, Snow performs “Poetry Man” in 1989.

Fire Island, New York, July 16, 2017

Photo by James Gavin