Italy's most awarded actress - Sophia Loren - is 89 years old today

Sophia Loren is 89 years old today.

Loren is widely recognized as the most awarded Italian actress.

She was the first actress of the talkie era to win an Academy Award for a non-English-speaking performance, for her portrayal of Cesira in Vittorio De Sica’s, Two Women.

In 1995, she received the Cecil B. DeMille Award for lifetime achievements, one of many such awards.

Her films include Houseboat (1958), El Cid (1961), Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow (1963), Marriage Italian-Style (1964) and A Special Day (1977).

In later years, she has appeared in American blockbusters such as Grumpier Old Men (1995) and Nine (2009).

In 1994, she starred in Robert Altman's film, Prêt-à-Porter, which earned her a Golden Globe nomination the same year. She has also achieved critical and commercial success in TV movies such as Courage (1986).

Loren first met Carlo Ponti in 1950 when she was 15 and he was 37. They married on Sept. 17, 1957.

However, Ponti was still officially married to his first wife Giuliana under Italian law because Italy did not recognize divorce at that time. The couple had their marriage annulled in 1962 to escape bigamy charges.

In 1965, Ponti obtained a divorce from Giuliana in France, allowing him to marry Loren on April 9, 1966.

They later became French citizens after their application was approved by then French President Georges Pompidou. Loren remained married to Ponti until his death on January 10, 2007 of pulmonary complications.

When asked in a November, 2009 interview if she is ever likely to marry again, Loren replied "No, never again. It would be impossible to love anyone else.”

French actress Michele Morgan and the filmmaker, Jean Cocteau, during the first Cannes film festival in 1946. Morgan received the best actress award for her performance in the movie, La Symphonie Pastorale.

The first annual Cannes Film Festival opened on this day in 1946 — 77 years ago — at the resort city of Cannes on the French Riviera.

The festival had intended to make its debut in September, 1939, but the outbreak of World War II forced the cancellation of the inaugural Cannes.

The world's first annual international film festival was inaugurated at Venice in 1932. By 1938, the Venice Film Festival had become a vehicle for Fascist and Nazi propaganda, with Benito Mussolini's Italy and Adolf Hitler's Germany dictating the choices of films and sharing the prizes among themselves. Outraged, France decided to organize an alternative film festival.

In June, 1939, the establishment of a film festival at Cannes, to be held from September 1st through 20, was announced in Paris. Cannes, an elegant beach city, lies southeast of Nice on the Mediterranean coast. One of the resort town's casinos agreed to host the event.

Films were selected and the filmmakers and stars began arriving in mid-August. Among the American selections was The Wizard of Oz. France offered The Nigerian and Poland entered The Black Diamond. The USSR brought the aptly titled, Tomorrow, It's War.

On the morning of September 1, the day the festival was to begin, Hitler invaded Poland. In Paris, the French government ordered a general mobilization, and the Cannes festival was called off after the screening of just one film: German American director William Dieterle's, The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Two days later, France and Britain declared war on Germany. World War II lasted six long years. In 1946, France's provincial government approved a revival of the Festival de Cannes as a means of luring tourists back to the French Riviera.

The festival began on September 20, 1946 and 18 nations were represented. The festival schedule included Austrian-American director Billy Wilder's, The Lost Weekend; Italian director Roberto Rossellini's, Open City; French director René Clement's, The Battle of the Rails; and British director David Lean's, Brief Encounter.

At the first Cannes, organizers placed more emphasis on creative stimulation between national productions than on competition. Nine films were honored with the top award: Grand Prix du Festival.

The Cannes Film Festival stumbled through its early years; the 1948 and 1950 festivals were canceled for economic reasons.

In 1952, the Palais des Festivals was dedicated as a permanent home for the festival, and in 1955, the Palme d'Or (Golden Palm) award for best film of the festival was introduced, an allusion to the palm-planted Promenade de la Croisette that parallels Cannes' celebrated beach.

In the 1950s, the Festival International du Film de Cannes came to be regarded as the most prestigious film festival in the world. It still holds that allure today, though many have criticized it as overly commercial. More than 30,000 people come to Cannes each May to attend the festival, about 100 times the number of film devotees who showed up for the first Cannes in 1946.

Due to the global pandemic, the festival will not take place in 2020, though much of the activity and judging will be online.

Sputnik digital artwork by Erik Simonsen

On Sept. 20, 1963 — 60 years ago — an optimistic and upbeat President John F. Kennedy suggested that the Soviet Union and the United States cooperate on a mission to mount an expedition to the moon. The proposal caught both the Soviets and many Americans off guard.

In 1961, shortly after his election as president, John F. Kennedy announced that he was determined to win the "space race" with the Soviets. Since 1957, when the Soviet Union sent a small satellite — Sputnik — into orbit around the earth, Russian and American scientists had been competing to see who could make the next breakthrough in space travel.

Outer space became another frontier in the Cold War. Kennedy upped the ante in 1961 when he announced that the United States would put a man on the moon before the end of the decade. Much had changed by 1963, however.

Relations with the Soviet Union had improved measurably. The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 had been settled peacefully. A "hot line" had been established between Washington and Moscow to help avert conflict and misunderstandings. A treaty banning the open air testing of nuclear weapons had been signed in 1963.

On the other hand, U.S. fascination with the space program was waning. Opponents of the program cited the high cost of the proposed trip to the moon, estimated at more than $20 billion.

In the midst of all of this, Kennedy, in a speech at the United Nations, proposed that the Soviet Union and United States cooperate in mounting a mission to the moon. "Why," he asked the audience, "should man's first flight to the moon be a matter of national competition?"

Kennedy noted "the clouds have lifted a little" in terms of U.S.-Soviet relations. "The Soviet Union and the United States, together with their allies, can achieve further agreements — agreements which spring from our mutual interest in avoiding mutual destruction," Kennedy said.

Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko applauded Kennedy's speech and called it a "good sign," but refused to comment on the proposal for a joint trip to the moon. In Washington, there was a good bit of surprise — and some skepticism — about Kennedy's proposal.

The "space race" had been one of the focal points of the Kennedy administration when it came to office, and the idea that America would cooperate with the Soviets in sending a man to the moon seemed unbelievable. Other commentators saw economics, not politics, behind the proposal.

With the soaring price tag for the lunar mission, perhaps a joint effort with the Soviets was the only way to save the costly program. What might have come of Kennedy's idea is unknown — just two months later, he was assassinated in Dallas.

His successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, abandoned the idea of cooperating with the Soviets but pushed ahead with the lunar program. In 1969, the United States landed the first men on the moon, thus winning a significant victory the "space race."

Thanks History.com

Upton Sinclair, author who wrote close to one hundred books in many genres, was born 145 years ago today.

Sinclair achieved popularity in the first half of the 20th Century, acquiring particular fame for his classic muckraking novel, The Jungle, in 1906. It exposed conditions in the U.S. meat packing industry, causing a public uproar that contributed in part to the passage a few months later of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act.

In 1919, he published, The Brass Check, a muckraking exposé of American journalism that publicized the issue of yellow journalism and the limitations of the “free press” in the United States.

Four years after the initial publication of The Brass Check, the first code of ethics for journalists was created.

Time magazine called him "a man with every gift except humor and silence."

In 1943, he won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

Sinclair also ran unsuccessfully for Congress as a Socialist, and was the Democratic Party nominee for Governor of California in 1934, though his highly progressive campaign was defeated.

In 1975 — 48 years ago — “Fame” gave David Bowie his first #1 in the U.S.

The song was co-written with John Lennon and Carlos Alomar.

With the Young Americans sessions mostly concluded by late 1974, the material was delayed while Bowie extricated himself from his contract with manager, Tony Defries. During this time, he was staying in New York, where he met John Lennon. The pair jammed together, leading to a one-day session at Electric Lady Studios in January, 1975.

There, Alomar had developed a guitar riff for Bowie's cover of "Footstompin'" by The Flairs, which Bowie thought was "a waste" to give to a cover. Lennon, who was in the studio with them, sang "ame" over the riff, which Bowie turned into "Fame" and he thereafter wrote the rest of the lyrics to the song.

Bowie would later describe the song as "nasty, angry," and fully admitted that the song was written "with a degree of malice" aimed at the Mainman management group with whom he had been working at the time.

In 1990, Bowie reflected: "I'd had very upsetting management problems and a lot of that was built into the song. I've left that all that behind me, now... I think fame itself is not a rewarding thing. The most you can say is that it gets you a seat in restaurants."

Bowie would later claim that he had "absolutely no idea" that the song would do so well as a single, saying "I wouldn't know how to pick a single if it hit me in the face.”

Paul Prestopino, 2016

Photo by Frank Beacham

Paul Prestopino, accompanist to a who’s who of major music groups for more than 50 years, was born 85 years ago today.

Prestopino played mandolin, banjo, guitar and about everything else, and was a mastering engineer formerly of the Record Plant and A&R Recording in New York City. He worked on the classic film, Standing in the Shadows of Motown.

Over the years, Prestopina performed or worked with the Chad Mitchell Trio, Peter Paul and Mary, Pete Seeger, John Denver, Judy Collins, Tom Paxton, Alice Cooper, Johnny Winter, Rick Derringer, Aerosmith, Loudon Wainwright III, Scarlet Rivera, Garland Jeffreys, Graham Parker, Bruce Springsteen, Neil Young, Bela Fleck and the Roots.

Prestopino died on July 16, 2023.

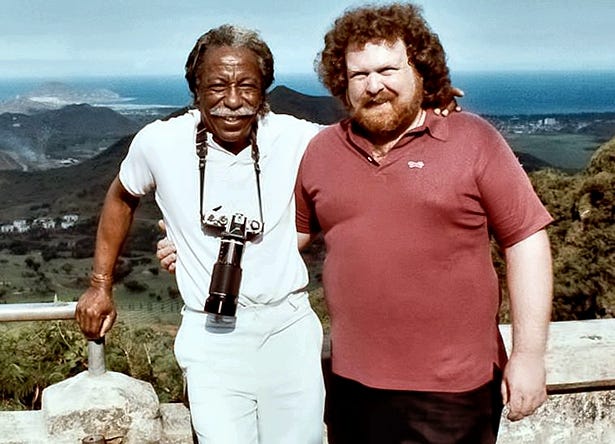

Gordon Parks and Frank Beacham on the last day of the shoot.

Working with Gordon Parks — A Personal Remembrance

In 1983, I based in Miami and was one of the few Betacam owners in the United States.

I got a call from Rick Smolen and David Cohen, who were preparing to host 50 of the world’s finest photographers in Hawaii in December, 1983, to photograph the entire state in a single day. In additional to publishing a book, they wanted to do a television documentary on the photo shoot.

The knew about the Betacam. I was recommended when they called Sony to inquire about who had the new one-piece camera recorder in the United States. This is how I was hired for a dream job, one that is still hard to believe to this day.

I would not only teach some of the world’s best photographers to use the Betacam, I would shoot footage myself for the documentary. But the deal even got better. I would work with two photographic legends—Gordon Parks, who would direct, and Douglas Kirkland, who would produce the show.

Parks was one of the world’s great photographers and filmmakers and Kirkland had been a staff photographer for both Look and Life magazines and had become famous for his amazing 1961 photos of Marilyn Monroe.

I flew to Hawaii in late November to prepare for the big day, which would be Dec. 2, 1983. The easy part was teaching the photographers to use the Betacam.

Most, in less than an hour, were better than the network photographers I was already working with. With this group, I learned quickly that a great eye with one camera easily translates to another. This was world class talent!

I had read up on Gordon Parks and was ready for this legend. As nice as he was, Parks was also a real taskmaster. It was clear we were there to work and work we did. Over the next week or so, I did things for Parks I would never have done for lesser mortals.

One very vivid memory was one of scariest shots of my life. More so than being shot at, in riots or in Latin American revolutions. On our first day working together, Gordon had me lay down on a runway at the Honolulu airport and shoot a 747 landing only a few feet above my head.

The plane roared, rattled and was deafening. The sight of the plane coming within a few feet of me was terrifying — to say the least — but I got the shot and Gordon was pleased. That, to me, was all that mattered.

After that day, we bonded, ate together and he began telling me stories of his extraordinary life and work. This went on for an entire week. We were normally joined by Doug Kirkland, who was equally adept at storytelling. Learning from these masters was something I would never forget.

The day of the photo shoot itself, I was pulled in a thousand directions. We had a fleet of 18 helicopters and my day was booked from sunrise shots early in the morning straight up until midnight. We crisscrossed Hawaii. I rolled hours of video tape on every conceivable subject. It was exhausting, but exhilarating.

On that day 64,800 still images were made. The book had 345 of them — one included our Betacam crew.

The photo coffee table book was published as “A Day in the Life of Hawaii” and the documentary we made aired on public television for years to come.

For me, it was one of the most exciting projects of my life.

Our Betacam documentary crew for the Day in the Life of Hawaii, 1983