Harry Smith — visual artist, experimental filmmaker, record collector, bohemian & mystic —was born 100 years ago

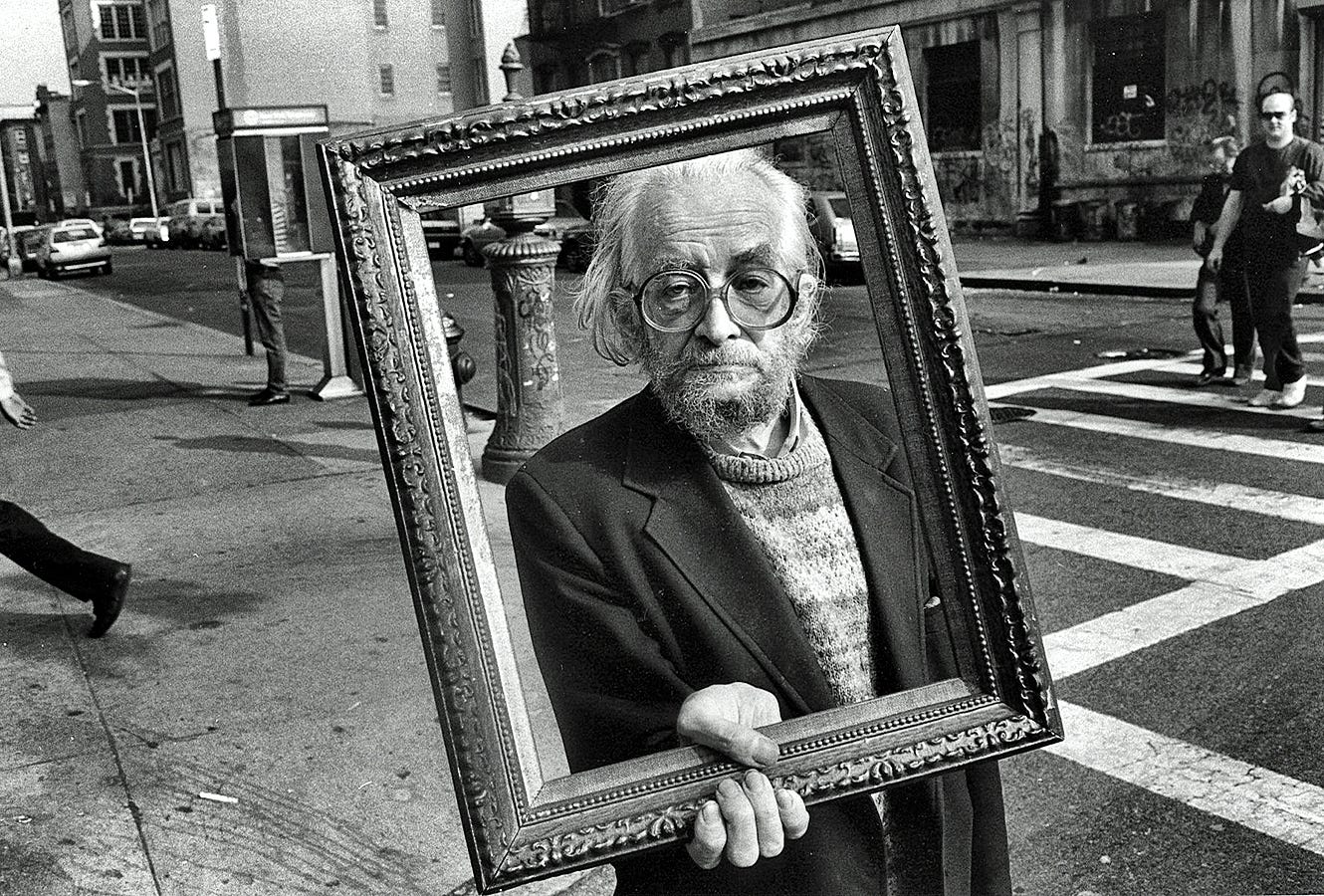

Photo by Gavin Friday

Harry Smith, visual artist, experimental filmmaker, record collector, bohemian, mystic and largely self-taught student of anthropology, was born 100 years ago.

Smith was an important figure in the Beat Generation scene in New York City. Besides his films, Smith is widely known for his influential Anthology of American Folk Music, drawn from his extensive collection of out-of-print commercial 78 rpm recordings.

Throughout his life Smith was an inveterate collector. In addition to records, he collected artifacts that included string figures, paper airplanes, Seminole textiles and Ukrainian Easter eggs.

Born in Portland, Oregon, Smith spent his earliest years in Washington state in the area between Seattle and Bellingham. As a child, he lived for a time with his family in Anacortes, Washington, a town on Fidalgo Island, where the Swinomish Indian reservation is located. He attended high school in nearby Bellingham.

Smith's parents, who didn't get along, lived in separate houses — meeting only at dinner time. Although poor, they gave their son an artistic education, including 10 years of drawing and painting lessons. For a time, it is said, they even ran an art school in their house.

Smith was a voracious reader and he recalled his father bringing him a copy of Carl Sandburg's folksong anthology, American Songbag. "We were considered some kind of 'low' family," Smith once said, "despite my mother's feeling that she was [an incarnation of] the Czarina of Russia."

Physically, Smith was undersized and had a curvature of the spine, which kept him from being drafted (a circumstance that later would disqualify him from benefitting from the G.I. Bill). During World War II, he took a job as a mechanic working nights on the construction of the tight, hard-to-reach interior of Boeing bomber planes, for which his short stature suited him.

Smith used the money he made from his job to buy blues records. It also enabled him to formally study anthropology at the University of Washington in Seattle for five semesters between 1942 and the fall of 1944.

He concentrated on American Indians, making numerous field trips to document the music and customs of the Lummi, whom he had gotten know through his mother's work with them. When the war ended, Smith, then 22, moved to the Bay Area of San Francisco, then home to a lively bohemian folk music and jazz scene.

As a collector of blues records, he had already been corresponding with the noted blues record aficionado, James McKune. He now also began seriously collecting old hillbilly music records from junk dealers and stores which were going out of business and even appeared as a guest on a folk music radio show hosted by Jack Spicer, the poet.

Smith was especially drawn to bebop, a new jazz form which had originated during impromptu jam sessions before and after paid performances. He went to after hours clubs where Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker could be heard in San Francisco.

At this time, he painted several ambitious jazz-inspired abstract paintings (since destroyed) and began making animated avant garde films featuring patterns that he painted directly on the film stock and which were intended to be shown to the accompaniment of bebop music.

In 1950, Smith received a Guggenheim grant to complete an abstract film, which enabled him first to visit and later move to New York City. He arranged for his collections, including his records, to be shipped to the East Coast. He said that "one reason he moved to New York was to study the Cabala. And, 'I wanted to hear Thelonious Monk play'."

When his grant money ran out, he brought what he termed "the cream of the crop" of his record collection to Moe Asch, president of Folkways Records, with the idea of selling it.

Instead, Asch proposed that the 27-year-old Smith use the material to edit a multi-volume anthology of American folk music in long playing format — then a newly developed, cutting edge medium — and he provided space and equipment in his office for Smith to work in.

The recording engineer on the project was Péter Bartók, son of the renowned composer and folklorist. The resultant Folkways anthology, issued in 1952 under the title, American Folk Music, was a compilation of recordings of folk music issued on hillbilly and race records that had previously been released commercially on 78 rpm.

These early recordings featured the "golden age" of the commercial country music industry between 1927 and 1932. When the Depression halted folk music sales, many of the artists went into obscurity. Originally issued as budget discs marketed to rural audiences, the records had long been known, collected and occasionally reissued by folklorists and aficionados.

But this was the first time such a large compilation was made available to affluent, non-specialist urban dwellers. LP discs could hold much more material than the old three-minute 78s and had greater fidelity and far less surface noise. The Anthology was packaged as a set of three, boxed albums. Each box front had a different color: red, blue, or green — in Smith's schema, representing the alchemical elements.

Priced at $25.00 ($216.00 in 2012) per two-disc set, they were a luxury item.

A fourth album, comprising topical songs from the Depression era, was originally planned by Asch and his long-time assistant, Marian Distler. It was never completed by Smith. It was issued in 2000, nine years after Smith’s death in CD format by Revenant Records with a 95-page booklet of tribute essays to Smith.

The music on Smith's anthology was performed by such artists as Clarence Ashley, Dock Boggs, The Carter Family, Sleepy John Estes, Mississippi John Hurt, Dick Justice, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Buell Kazee and Bascom Lamar Lunsford.

It had a huge impact on the folk and blues revivals of the 1950s and 60s. The songs were covered by my artists including The New Lost City Ramblers, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez.

Rock critic Greil Marcus, in his liner-note essay for the 1997 Smithsonian reissue, quoted musician Dave van Ronk's avowal that "We all knew every word of every song on it, including the ones we hated."

In addition to compiling the Folkways anthology, Smith was also instrumental in getting Folkways to produce (on its Broadside label) the The Fugs First Album (1965), now considered the first "folk rock" album.

A regular visitor to the Peace Eye bookstore, in Manhattan's East Village on 10th St. between Avenues B and Ave C, founded in 1965 by poet Ed Sanders, Smith had advised Sanders which books about Native American studies the store ought to stock. When Sanders and Tuli Kupferberg formed the Fugs, they rehearsed at Peace Eye. "Thanks to Harry," writes Sanders, "the band was able to record an album within weeks of forming."

Peter Stampfel recalls that, as the album's editor and producer, "Harry's contribution to the proceedings were his presence, inspiration and best of all, smashing a wine bottle against the wall while we were recording 'Nothing.'"

Harry Smith lived at the Hotel Chelsea on West 23rd Street in New York City from 1968 to 1975, after which he was "sometimes 'stranded' at hotels where he would owe so much money he couldn't leave, and he was too famous just to be thrown out."

This was the case at the Breslin Hotel at 28th and Broadway, where Smith lived until 1985, when his friend, poet Allen Ginsberg, took him into his home on East 12th Street.

While living with Ginsberg, Smith designed the cover for two of Ginsberg's books, White Shroud and Collected Poems, as well as continuing to work on his own films and to record ambient sounds. By this time, Smith was suffering from severe health and dental problems, as well as alcohol addiction. He proved a difficult guest.

Ginsberg's psychiatrist finally told him that Smith would have to leave because he was bad for Ginsberg's blood pressure (Ginsberg was already suffering from the cardiovascular disease that was to kill him).

In 1988, Ginsberg arranged for Smith to teach shamanism at the Naropa Institute (now Naropa University) in Boulder, Colorado. When Ginsberg, who was paying all of Smith's expenses, realized Smith was using the money he was sending him for rent to buy alcohol, he hired Rani Singh, then a student at Naropa, to look after him.

But this was not before Smith had amassed substantial debts that Ginsberg would be responsible for. Singh, now an author and art curator, has since devoted much of her life to furthering Smith's legacy.

In 1991, Smith suffered a bleeding ulcer followed by cardiac arrest in Room 328 at the Hotel Chelsea in New York City. His friend, poet Paola Igliori, described him as dying in her arms "singing as he drifted away." Smith was pronounced dead one hour later at St. Vincent's Hospital.

Smith's ashes were long in the care of his late friend, longtime participant in New York's Beat scene, Rosemarie "Rosebud" Feliu-Pettet, who was Smith's "spiritual wife."

Some Crazy Magic: Meeting Harry Smith

A animated interpretation of John Cohen’s first meeting with Harry Smith

Bob Hope was born 120 years ago today.

An English-born American comedian, vaudevillian, actor, singer, dancer, author and athlete, Hope appeared on Broadway, vaudeville, movies, television and radio. He was noted for his numerous United Service Organizations (USO) shows entertaining American military personnel, making 57 tours for the USO between 1942 and 1988.

Over a career spanning 60 years (1934 to 1994), Hope appeared in over 70 films and shorts, including a series of "Road" movies co-starring Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour.

In addition to hosting the Academy Awards fourteen times, he appeared in many stage productions and television roles, and was the author of fourteen books.

Hope died at age 100 in 2003.

Here, Hope and James Cagney do the great dance routine from the 1955 movie, The Seven Little Foys. Hope plays the role of Eddie Foy.

Bob Hope: A Personal Remembrance

Though Bob Hope was not a comedian for my anti-Vietnam generation, I had one very funny experience with him.

During football season in college — to earn beer money — I shot two college games on 16mm film each Saturday. The first was at Clemson University in the afternoon. Then I’d fly in a small Cessna plane to the University of South Carolina for the night game. After shooting both games, I’d work all night processing and editing the film for the coaches TV shows the next day.

One Saturday afternoon, Bob Hope was in the Clemson press box. He was performing a show later that night on the campus. He stood two feet behind me — and as has happened before with other comedians — he decided I was his target.

I tried to ignore him, since I had to concentrate on operating the camera to shoot the game. But Hope, sensing a kill, would have none of that. He started a non-stop stream of very filthy jokes. Much of his riff was very funny and far more raunchy than the sanitized fluff I had heard him do on television.

Before long, I started laughing hysterically. The man was hilarious. This pleased Hope no end, and he kept piling on with more. I asked him to stop, since I could barely concentrate on shooting the game. But, no way — he wouldn’t quit. As I laughed harder and harder, he kept it up to the point of (my) near exhaustion.

When the game finally ended, I looked at Hope and he just smiled. He was very pleased that he had totally disrupted my entire film shoot. We shook hands and he left the press box, never to be seen by me again.

That’s all I remember about Bob Hope.

Manuel Noriega: A Personal Remembrance

Manuel Noriega died six years ago today in Panama City at the age of 83. He had been in intensive care after complications developed from surgery to remove a benign brain tumor. At the time, he was still in prison, but had been granted house arrest to prepare for the operation.

A remembrance of Noriega is permanently seared into my mind. I will never forget him.

On Panama’s Contadora Island in 1979, while covering the late Shah of Iran for NBC News, I was arrested by Noriega, then Panama’s chief of military intelligence. It was early morning, and I exited the shower to find Noriega in the bathroom pointing an Uzi submachine gun at me. He ordered me to get dressed and then drove me in a jeep to a government-owned house on the island.

He said I was using a walkie-talkie that interfered with his private frequency. The walkie-talkie, which I bought in a gift shop on the island, was being used to communicate with the rest of my crew.

I apologized, but Noriega was having none of it. He made me and the other crew members he had also arrested sit on a couch and look at his porno magazines, while hysterically laughing at us. It became clear quickly that Noriega was a real sicko.

Time dragged by as we quietly waited, having no idea of our fate with this madman. Later that day, he took us in his jeep to the island’s airstrip. Our bags, removed from our rooms and hastily packed by his forces, were waiting there for us. We were told to board the plane and were flown back to Miami.

After returning to NBC’s offices in Miami, the phone rang and it was the president of Panama, General Omar Torrijos calling. Torrijos profusely apologized for Noriega’s actions to Don Browne, NBC’s bureau chief, and invited us back to Contadora Island to complete coverage of the Shah’s vacation stay there.

He absolutely promised no more trouble. Anxious to make the money on this lucrative job, I agreed to return with my crew. (Yes, I was VERY stupid back in those days!)

But first, when we arrived back in Panama, we visited Gen. Torrijos, who warmly welcomed us back to his country. He asked if I could deliver a box of Cuban cigars to his friend, Sen. Edward Kennedy, who liked them.

Each cigar had a band that had the words General Torrijos printed on it — a personal gift from Fidel Castro. I promised to send the cigars — illegal in the United States — to Kennedy when we returned. (That was not without skimming off the top row for myself!)

The rest of our trip on Contadora Island was without incident and we returned home a week and a half later.

A footnote to this story: Gen. Torrijos died in a plane accident on July 31, 1981. Colonel Roberto Díaz Herrera, a former associate of Noriega, claimed that the actual cause for the accident was a bomb and that Noriega was behind the incident.

Somehow, I was never surprised by this. Noriega became the defacto leader of the country before his arrest.

Melissa Etheridge is 62 years old today.

A singer-songwriter, guitarist and activist, Etheridge is known for her mixture of confessional lyrics, pop-based folk-rock and raspy, smoky vocals. She has also been an iconic gay and lesbian activist since her public coming out in January, 1993.

Born in Leavenworth, Kansas, the younger of two girls, Etheridge’s interest in music began early when she picked up her first guitar at eight. She began to play in all-men country music groups throughout her teenage years, until she moved to Boston to attend the Berklee College of Music.

While in Berklee, Etheridge played the club circuit around Boston. After three semesters, she decided to drop out of Berklee and head to Los Angeles to attempt a career in music. She was discovered in a bar called Vermie's in Pasadena.

Etheridge had made some friends on a women's soccer team and those new friends came to see her play. One of the women was Karla Leopold, whose husband, Bill Leopold, was a manager in the music business. Karla convinced Bill to see her perform live. He was impressed, and has remained a pivotal part of Etheridge's career ever since.

This, in addition to her gigs in lesbian bars around Los Angeles, led to her discovery by Island Records chief, Chris Blackwell. She received a publishing deal to write songs for movies including the 1986 movie, Weeds.

In 1985, prior to her signing, Etheridge sent her demo to Olivia Records, a lesbian record label, but was ultimately rejected. She saved the rejection letter, signed by "the women of Olivia," which was later featured in Intimate Portrait: Melissa Etheridge, the Lifetime Television documentary of her life.

After an unreleased first effort that was rejected by Island Records as being too polished and glossy, she completed her stripped-down self-titled debut in just four days. Her eponymous debut album, Melissa Etheridge, was an underground hit. A single from the album, "Bring Me Some Water," was a hit.

At the time of the album's release, it was not generally known that Etheridge was a lesbian. While on the road promoting the album, she paused in Memphis to be interviewed for the radio syndication, Pulsebeat — Voice of the Heartland, explaining the intensity of her music by saying:

"People think I'm really sad — or really angry. But my songs are written about the conflicts I have...I have no anger toward anyone else." She invited the radio syndication producer to attend her concert that night. He did and was surprised to find himself one of the few men in attendance.

Etheridge followed up her first album's modest success by contributing background vocals to Don Henley's album, The End of the Innocence. She went into the studio and recorded her sophomore effort, Brave and Crazy, which was released in 1989. The album peaked at #22 on the Billboard charts (equal to her first album).

Etheridge then went on the road, taking a page from one of her musical influence, Bruce Springsteen, and built a loyal fan base. She has covered Springsteen’s songs "Thunder Road" and "Born to Run" during live shows.

On September 21, 1993, Etheridge released what would become her mainstream breakthrough album, Yes I Am.

Co-produced with former The Police and Genesis producer Hugh Padgham, Yes I Am spent 138 weeks on the Billboard 200 charts and peaked at #15 and scored mainstream hits "Come to My Window" and her only Billboard Top 10 single, "I'm the Only One." It also hit #1 on Billboard's Adult Contemporary chart.

In October, 2004, Etheridge was diagnosed with breast cancer. At the 2005 Grammy Awards, she made a return to the stage and, although bald from chemotherapy, performed a tribute to Janis Joplin with the song "Piece of My Heart."

Here, Etheridge performs “I’m the Only One”

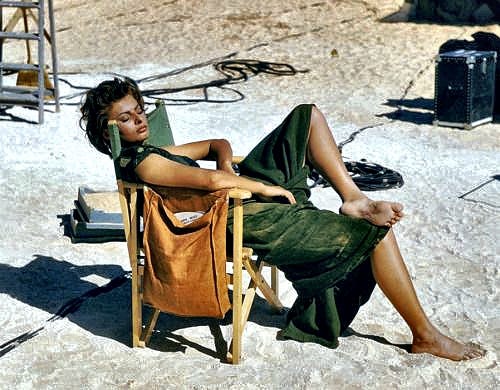

Sophia Loren on the set of Legend of the Lost, 1957