Folk singer-songwriter Steve Goodman was born 75 years ago today

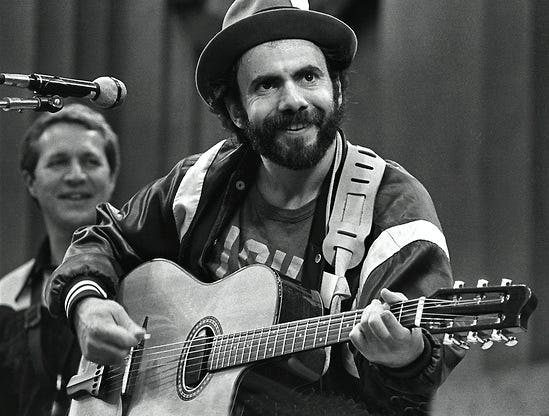

Steve Goodman, Bread and Roses Festival, Sept. 3, 1978

Photo by Jon Sievert

Steve Goodman was born 75 years ago today.

A folk music singer-songwriter from Chicago, Goodman wrote "City of New Orleans," made popular by Arlo Guthrie and Willie Nelson.

Born on Chicago's North Side to a middle-class Jewish family, Goodman began writing and performing songs as a teenager, after his family had moved to the near north suburbs. He graduated from Maine East High School in Park Ridge, Illinois in 1965, where he was a classmate of Hillary Rodham Clinton.

In the fall of 1965, he entered the University of Illinois and pledged Sigma Alpha Mu (Sammies) fraternity where he, Ron Banyon and Steve Hartmann formed a popular rock cover band, "The Juicy Fruits." He left college after one year to pursue his musical career.

In the early spring of 1967, Goodman went to New York, staying for a month in a Greenwich Village brownstone across the street from the Cafe Wha?, where he performed regularly during his brief stay.

Returning to Chicago, he intended to restart his education but he dropped out again to pursue his musical dream full-time after discovering the cause of his continuous fatigue was actually leukemia, the disease that would be present during the entirety of his recording career, until his death in 1984.

In 1968, Goodman began performing at the Earl of Old Town in Chicago and attracted a following. Within a year, Goodman was a regular performer in Chicago, while attending Lake Forest College. During this time Goodman supported himself by singing advertising jingles.

In September, 1969, he met Nancy Pruter (sister of R&B writer, Robert Pruter), who was attending college while supporting herself as a waitress. They were married in February, 1970.

Though he experienced periods of remission, Goodman never felt that he was living on anything other than borrowed time, and some critics, listeners and friends have said that his music reflects this sentiment.

His wife, Nancy, writing in the liner notes to the posthumous collection, No Big Surprise, characterized him this way:

“Basically, Steve was exactly who he appeared to be: an ambitious, well-adjusted man from a loving, middle-class Jewish home in the Chicago suburbs, whose life and talent were directed by the physical pain and time constraints of a fatal disease which he kept at bay, at times, seemingly by willpower alone . . . Steve wanted to live as normal a life as possible, only he had to live it as fast as he could . . . He extracted meaning from the mundane.”

Goodman's songs first appeared on Gathering at The Earl of Old Town, an album produced by Chicago record company, Dunwich, in 1971. As a close friend of Earl Pionke, the owner of the folk music bar, Goodman performed at The Earl dozens of times, including customary New Year's Eve concerts. He also remained closely involved with Chicago's Old Town School of Folk Music, where he had met and mentored his good friend, John Prine.

Later in 1971, Goodman was playing at a Chicago bar called the Quiet Knight as the opening act for Kris Kristofferson. Impressed with Goodman, Kristofferson introduced him to Paul Anka, who brought Goodman to New York to record some demos. These resulted in Goodman signing a contract with Buddah Records.

All this time, Goodman had been busy writing many of his most enduring songs, and this avid songwriting would lead to an important break for him. While at the Quiet Knight, Goodman saw Arlo Guthrie and asked to be allowed to play a song for him.

Guthrie grudgingly agreed, on the condition that Goodman buy him a beer first. Guthrie said he would listen to Goodman for as long as it took him to drink the beer.

Goodman played "City of New Orleans," which Guthrie liked enough that he asked to record it. Guthrie's version of Goodman's song became a Top 20 hit in 1972, and provided Goodman with enough financial and artistic success to make his music a full-time career. The song, about the Illinois Central's City of New Orleans train, would become an American standard, covered by such musicians as Johnny Cash, Judy Collins, Chet Atkins and Willie Nelson.

In 1974, singer David Allan Coe achieved considerable success on the country charts with Goodman's and John Prine's "You Never Even Call Me By My Name," a song which good-naturedly spoofed stereotypical country music lyrics. Prine refused to take a songwriter's credit of the song, although Goodman bought Prine a jukebox as a gift from his publishing royalties.

Goodman's success as a recording artist was more limited. Although he was known in folk circles as an excellent and influential songwriter, his albums received more critical than commercial success.

One of Goodman's biggest hits was a song he didn't write – "The Dutchman," written by Michael Peter Smith. During the mid- and late-seventies, Goodman became a regular guest on Easter Day on Vin Scelsa’s radio show in New York City. Scelsa’s personal recordings of these sessions eventually led to an album of selections from these appearances, The Easter Tapes.

In 1977, Goodman performed on the Tom Paxton live album, New Songs From the Briarpatch (Vanguard Records), which contained some of Paxton's topical songs of the 1970s, including "Talking Watergate" and "White Bones of Allende," as well as a song dedicated to Mississippi John Hurt entitled "Did You Hear John Hurt?"

On September 20, 1984, Goodman died of leukemia at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle. He had anointed himself with the tongue-in-cheek nickname “Cool Hand Leuk” (other nicknames included “Chicago Shorty” and “The Little Prince”) during his illness. He was 36 years old.

Here, Goodman performs “City of New Orleans.”

Newport, 1965 — 58 years ago today

Bob Dylan’s band included Mike Bloomfield, guitar; Jerome Arnold, bass; Al Kooper, organ, Barry Goldberg, piano and Sam Lay, drums.

Photo courtesy Newportfolk.com

Before he took the stage at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival — the annual event that had given him his first real national exposure one year earlier — Bob Dylan was introduced by Ronnie Gilbert, a member of The Weavers:

"And here he is...take him, you know him, he's yours."

In his 2004 memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, Dylan would write about how he "failed to sense the ominous forebodings in the introduction."

One year later, he would learn just how possessive the Newport audiences felt toward him.

On this day in 1965 — 58 years ago — Bob Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival, performing a rock-and-roll set publicly for the very first time while shouts and boos came from some dismayed fans in the audience. Six weeks earlier, Bob Dylan had recorded the single that marked his move out of acoustic folk and into the idiom of electrified rock and roll.

"Like A Rolling Stone" had only been released five days before his appearance at Newport, however, so most in the audience had no idea what lay in store for them. Neither did festival organizers, who were as surprised to see Dylan's crew setting up heavy sound equipment during sound check as that evening's audience would be to hear what came out of it.

With Al Kooper and The Paul Butterfield Blues Band including Mike Bloomfield on guitar, Barry Goldberg on piano, Jerome Arnold on bass and Sam Lay on drums backing him, Dylan took to the stage with his Fender Stratocaster on the evening of July 25 and launched into an electrified version of "Maggie's Farm."

Almost immediately, the jeering and yelling came from some audience members. Some said it was due to bad sound, some said it was due to the short set, while others complained of the folk singer going electric. Dylan's vocals were unintelligible to many in the audience.

But it was clear by Dylan's next number, the now-classic "Like A Rolling Stone" — that the old folk singer was headed in a new artistic direction. Dylan's performance at Newport in 1965 stands as a pivotal moment in the history of American music.

By severing his ties to the old-guard folk establishment, Dylan sought to escape the limitations imposed by his former champions, the well-meaning purists of traditional musical expression. The rigors of their intellectual understanding of "folk music" — who should play it, how it should be made, what it should be about — were stifling to Dylan's own intellectual freedom.

He needed to purge his music of its "authenticity" and move beyond the musical category he had so willingly insinuated himself into since meeting Woody Guthrie in 1961. It was time for his music to be entirely about Bob Dylan, not about some coal mining strike in 1931.

And what did the man himself think of the unfriendly reception he received from what should have been the friendliest of audiences? Some say he was extremely shaken at the time, but with four decades of hindsight, his feelings were clear.

Reflecting on Ronnie Gilbert's "Take him, he's yours" comment, Dylan wrote, "What a crazy thing to say! Screw that. As far as I knew, I didn't belong to anybody then or now."

Thanks History.com and other sources.

Emmett Till was born 82 years ago today.

Till was an African-American boy who was murdered in Mississippi at the age of 14 after reportedly flirting with a white woman.

Visiting relatives from Chicago in Money, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta region, the trouble started when Till spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the married proprietor of a small grocery store there.

Several nights later, Bryant's husband, Roy, and his half-brother, J. W. Milam, arrived at Till's great-uncle's house where they took Till, transported him to a barn, beat him and gouged out one of his eyes.

Then they shot Till through the head and disposed of his body in the Tallahatchie River, weighting it with a 70-pound cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. Till’s body was discovered and retrieved from the river three days later.

Till was returned to Chicago and his mother, who had raised him mostly by herself, insisted on a public funeral service with an open casket to show the world the brutality of the killing.

Tens of thousands attended his funeral or viewed his casket and images of his mutilated body were published in black magazines and newspapers, rallying popular black support and white sympathy across the U.S. Intense scrutiny was brought to bear on the condition of black civil rights in Mississippi, with newspapers around the country critical of the state.

Although initially local newspapers and law enforcement officials decried the violence against Till and called for justice, they soon began responding to national criticism by defending Mississippians, which eventually transformed into support for the killers.

The trial attracted a vast amount of press attention. Bryant and Milam were acquitted of Till's kidnapping and murder, but only months later, in a magazine interview, protected against double jeopardy, they admitted to killing him.

Till's murder is noted as a pivotal event motivating the African-American Civil Rights Movement. Problems identifying Till affected the trial, partially leading to Bryant's and Milam's acquittals, and the case was officially reopened by the United States Department of Justice in 2004.

As part of the investigation, the body was exhumed and autopsied resulting in a positive identification. He was reburied in a new casket, which is the standard practice in cases of body exhumation.

His original casket was donated to the Smithsonian Institution. Events surrounding Emmett Till's life and death, according to historians, continue to resonate, and almost every story about Mississippi returns to Till, or the region in which he died, in "some spiritual, homing way."

Till continues to be the focus of literature and memorials. A statue was unveiled in Denver in 1976 (and has since been moved to Pueblo, Colorado) featuring Till with Martin Luther King, Jr. Till was included among the forty names of people who had died in the Civil Rights Movement (listed as martyrs) on the granite sculpture of the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, dedicated in 1989.

In 1991, a seven-mile stretch of 71st Street in Chicago, was renamed "Emmett Till Road." Mamie Till-Mobley, Emmett’s mother, attended many of the dedications for the memorials, including a demonstration in Selma, Alabama on the 35th anniversary of the march over the Edmund Pettis Bridge.

She later wrote in her memoirs” "I realized that Emmett had achieved the significant impact in death that he had been denied in life. Even so, I had never wanted Emmett to be a martyr. I only wanted him to be a good son. Although I realized all the great things that had been accomplished largely because of the sacrifices made by so many people, I found myself wishing that somehow we could have done it another way."

Till-Mobley died in 2003, the same year her memoirs were published.

James McCosh Elementary School in Chicago, where Till had been a student, was renamed the "Emmett Louis Till Math And Science Academy" in 2005.

The "Emmett Till Memorial Highway" was dedicated between Greenwood and Tutwiler, Mississippi, the same route his body took to the train station on its way to Chicago.

In 2007, Tallahatchie County issued a formal apology to Till's family, reading "We the citizens of Tallahatchie County recognize that the Emmett Till case was a terrible miscarriage of justice. We state candidly and with deep regret the failure to effectively pursue justice. We wish to say to the family of Emmett Till that we are profoundly sorry for what was done in this community to your loved one.”

The same year, Georgia congressman John Lewis, whose skull was fractured while being beaten during the 1965 Selma march, sponsored a bill that provides a plan for investigating and prosecuting unsolved Civil Rights era murders. The Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act was signed into law in 2008.

The funeral of Emmett Till

Roy Bryan, left, and J.W. Milam on trial in Sumner, Mississippi, September, 1955 for the killing of Emmett Till

Photo by Ed Clark

The Emmett Till murder trial, 1955

Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam were tried for the murder of Till in late 1955, but acquitted by an all-white Mississippi jury.

Protected by the double jeopardy clause, Bryant and Milam admitted killing Till in a 1956 magazine interview. The widely publicized trial is considered a pivotal event in the Civil Rights Movement.

Shown in the above photo is the all-white jury .

Bob Dylan performs “The Death of Emmett Till”

Walter Brennan, one of three actors to win three Academy Awards, was born 129 years ago.

Brennan joined Jack Nicholson and Daniel Day-Lewis in having won three Oscars. A character actor, Brennan won as Best Supporting Actor in 1936, 1938 and 1940.

Born in Lynn, Massachusetts, Brennan became interested in acting while in school and began to perform in vaudeville at the age of 15. While working as a bank clerk, he enlisted in the Army and served as a private with the 101st Field Artillery Regiment in France during World War I.

Following the war, he moved to Guatemala and raised pineapples before settling in Los Angeles. During the 1920s, he made a fortune in the real estate market, but he lost most of his money during the Great Depression.

Finding himself broke, Brennan began taking extra parts in 1925 and then bit parts in as many films as he could, including Texas Cyclone and Two Fisted Law with another newcomer to Hollywood, John Wayne. He also had bit parts in The Invisible Man (1933), the Three Stooges short Woman Haters (1934) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935), in which he enjoyed a brief speaking part, and also worked as a stunt man.

In the 1930s, Brennan began appearing in higher-quality films and received more substantial roles as his talent was recognized. This culminated with his receiving the first Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role as Swan Bostrom in the period film, Come and Get It (1936).

Two years later, he portrayed town drunk and accused murderer Muff Potter in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

Throughout his career, Brennan was frequently called upon to play characters considerably older than he was in real life. The loss of many teeth in a 1932 accident, rapidly thinning hair, thin build and unusual vocal intonations all made him seem older than he really was.

He used these features to great effect. In many of his film roles, Brennan wore dentures. In Northwest Passage – a film set in the late-18th century – he wore a special dental prosthesis which made him appear to have rotting and broken teeth.

For director Jean Renoir's first American film, Brennan played the top-billed lead in Swamp Water (1941), a drama also featuring Walter Huston and starring Dana Andrews. In Sergeant York (also 1941), he played a sympathetic preacher and dry-goods store owner who advised the title character, played by Gary Cooper. Brennan and Cooper appeared in six films together.

In 1942, he played reporter Sam Blake, who befriended and encouraged Lou Gehrig (also played by Cooper) in Pride of the Yankees. He was particularly skilled in playing the sidekick to the protagonist or as the "grumpy old man" in films such as To Have and Have Not (1944), the Humphrey Bogart vehicle which introduced Lauren Bacall.

Though he was hardly ever cast as the villain, notable exceptions were his roles as Judge Roy Bean in The Westerner (1940) with Gary Cooper, for which he won his third best supporting actor Academy Award, 'Old Man' Clanton in My Darling Clementine (1946) opposite Henry Fonda and the murderous Colonel Jeb Hawkins in the James Stewart episode of the Cinerama production, How the West Was Won (1962).

From 1957–1963, he starred in the ABC television series The Real McCoys, a situation comedy about a poor West Virginia family that relocated to a farm in Southern California.

Film historians and critics have long regarded Brennan as one of the finest character actors in motion picture history. In all, he appeared in more than 230 film and television roles during a career that spanned nearly five decades.

Brennan died from emphysema at the age of 80 in Oxnard, California in 1974.

Benny Benjamin, drummer for Motown’s studio band, The Funk Brothers, was born 98 years ago today.

Nicknamed Papa Zita, Benjamin was a native of Birmingham, Alabama. He originally learned to play drums in the style of the big band jazz groups.

In 1958, Benjamin became Motown's first studio drummer, where he was noted for his dynamic style. Several Motown record producers, including Berry Gordy, refused to work on any recording sessions unless Benjamin was the drummer and James Jamerson was the bassist.

The Beatles singled out Benjamin’s drumming style upon meeting him in the UK. He was influenced by the work of drummers, Buddy Rich and Tito Puente.

Among the Motown songs Benjamin performed the drum tracks for are "Money (That's What I Want)" by Barrett Strong and "Do You Love Me" by The Contours; as well as later hits such as "Get Ready" and "My Girl" by The Temptations, "Uptight (Everything's Alright)" by Stevie Wonder, "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" by Gladys Knight & the Pips and "Going To A Go-Go" by The Miracles.

By the late 1960s, Benjamin struggled with drug and alcohol addiction, and fellow Funk Brothers, Uriel Jones and Richard "Pistol" Allen, increasingly recorded more of the drum tracks for the studio's releases.

Benjamin died on April 20, 1969 of a stroke at age 43, and was inducted into the "Sidemen" category of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2003.

Candy Cigarette, 1969

Photo by Sally Mann