Fifty-four years ago today, the first man walked on the moon

Fifty-four years ago today — at 10:56 p.m. EDT — American astronaut Neil Armstrong, 240,000 miles from Earth, spoke these words to more than a billion people listening at home:

"That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."

Stepping off the lunar landing module Eagle, Armstrong became the first human to walk on the surface of the moon.

The American effort to send astronauts to the moon has its origins in a famous appeal President John F. Kennedy made to a special joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961: "I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth."

At the time, the United States was still trailing the Soviet Union in space developments, and Cold War-era America welcomed Kennedy's bold proposal.

In 1966, after five years of work by an international team of scientists and engineers, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) conducted the first unmanned Apollo mission, testing the structural integrity of the proposed launch vehicle and spacecraft combination.

Then, on January 27, 1967, tragedy struck at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, when a fire broke out during a manned launch-pad test of the Apollo spacecraft and Saturn rocket. Three astronauts were killed in the fire.

Despite the setback, NASA and its thousands of employees forged ahead, and in October 1968, Apollo 7, the first manned Apollo mission, orbited Earth and successfully tested many of the sophisticated systems needed to conduct a moon journey and landing.

In December of the same year, Apollo 8 took three astronauts to the dark side of the moon and back, and in March, 1969 Apollo 9 tested the lunar module for the first time while in Earth orbit. Then in May, the three astronauts of Apollo 10 took the first complete Apollo spacecraft around the moon in a dry run for the scheduled July landing mission.

At 9:32 a.m. on July 16, with the world watching, Apollo 11 took off from Kennedy Space Center with astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin Aldrin Jr., and Michael Collins aboard.

Armstrong, a 38-year-old civilian research pilot, was the commander of the mission. After traveling 240,000 miles in 76 hours, Apollo 11 entered into a lunar orbit on July 19. The next day, at 1:46 p.m., the lunar module Eagle, manned by Armstrong and Aldrin, separated from the command module, where Collins remained.

Two hours later, the Eagle began its descent to the lunar surface, and at 4:18 p.m. the craft touched down on the southwestern edge of the Sea of Tranquility. Armstrong immediately radioed to Mission Control in Houston, Texas, a famous message: "The Eagle has landed."

At 10:39 p.m., five hours ahead of the original schedule, Armstrong opened the hatch of the lunar module.

As he made his way down the lunar module's ladder, a television camera attached to the craft recorded his progress and beamed the signal back to Earth, where hundreds of millions watched in great anticipation.

At 10:56 p.m., Armstrong spoke his famous quote, which he later contended was slightly garbled by his microphone and meant to be "that's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind." He then planted his left foot on the gray, powdery surface, took a cautious step forward and the first human had walked on the moon.

Buzz Aldrin joined him on the moon's surface at 11:11 p.m., and together they took photographs of the terrain, planted a U.S. flag, ran a few simple scientific tests, and spoke with President Richard M. Nixon via Houston.

By 1:11 a.m. on July 21, both astronauts were back in the lunar module and the hatch was closed. The two men slept that night on the surface of the moon, and at 1:54 p.m. the Eagle began its ascent back to the command module.

Among the items left on the surface of the moon was a plaque that read: "Here men from the planet Earth first set foot on the moon — July, 1969 A.D. — We came in peace for all mankind."

At 5:35 p.m., Armstrong and Aldrin successfully docked and rejoined Collins, and at 12:56 a.m. on July 22 Apollo 11 began its journey home. It safely splashed down in the Pacific Ocean at 12:51 p.m. on July 24.

There would be five more successful lunar landing missions, and one unplanned lunar swing-by, Apollo 13. The last men to walk on the moon, astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt of the Apollo 17 mission, left the lunar surface on December 14, 1972.

The Apollo program was a costly and labor intensive endeavor, involving an estimated 400,000 engineers, technicians and scientists. It cost $24 billion (close to $100 billion in today's dollars).

The expense was justified by Kennedy's 1961 mandate to beat the Soviets to the moon. After the feat was accomplished, ongoing missions lost their viability.

Thanks History.com.

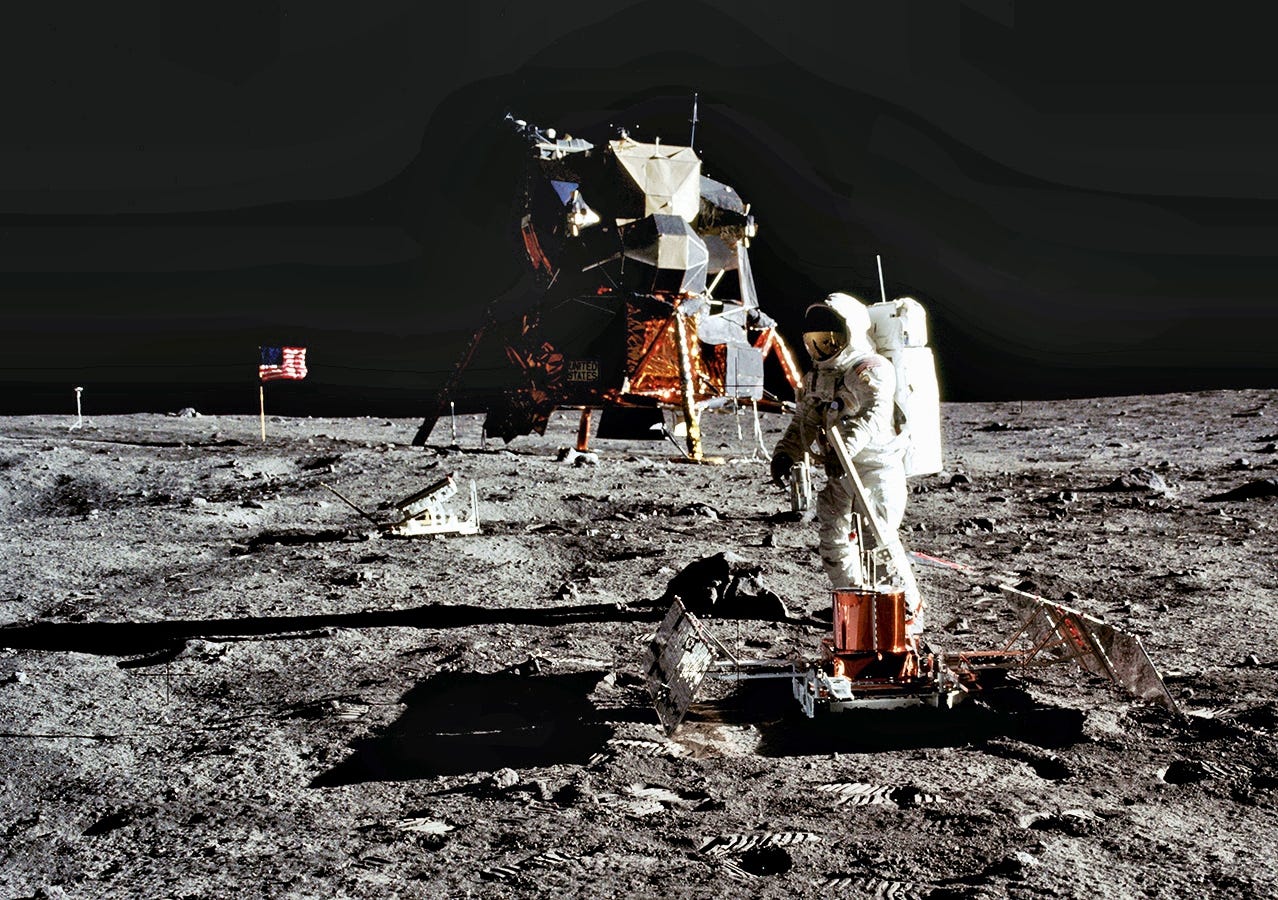

Neil Armstrong on the moon

Photo by Buzz Aldrin

Carlos Santana, Woodstock, 1969

Carlos Santana is 76 years old today.

Santana is a Mexican and American musician who became famous in the late 1960s and early 1970s with his band, Santana, which pioneered a fusion of rock and Latin American music.

The band's sound featured his melodic, blues-based guitar lines set against Latin and African rhythms featuring percussion instruments such as timbales and congas not generally heard in rock music. Santana continued to work in these forms over the following decades.

Born at Autlán de Navarro, Jalisco, Mexico, Santana learned to play the violin at age five and the guitar at age eight. His younger brother, Jorge Santana, would also become a professional guitarist.

Young Carlos was heavily influenced by Ritchie Valens at a time when there were very few Latinos in American rock and pop music. The family moved from Autlán de Navarro to Tijuana, the city on Mexico's border with California, and then San Francisco.

Santana stayed in Tijuana, but later joined his family in San Francisco and graduated from James Lick Middle School and in 1965 from Mission High School. He was accepted at California State University, Northridge, and Humboldt State University, but turned down these offers.

Santana got the chance to see his idols (most notably B.B. King) perform live in San Francisco. He also was introduced to a variety of new musical influences, including jazz and folk music, and witnessed the growing hippie movement centered in San Francisco in the 1960s.

After several years spent working as a dishwasher in a diner and busking for spare change, Santana decided to become a full-time musician. In 1966, he gained prominence by a series of accidental events.

Santana was a frequent spectator at Bill Graham's Fillmore West. During a Sunday matinee show, Paul Butterfield was slated to perform there but was unable to do so as a result of being intoxicated. Bill Graham assembled an impromptu band of musicians he knew primarily through his connections with the Grateful Dead, Butterfield's own band and Jefferson Airplane, but he had not yet picked all of the guitarists at the time.

Santana's manager, Stan Marcum, immediately suggested to Graham that Santana join the impromptu band and Graham assented. During the jam session, Santana's guitar playing and solo gained the notice of both the audience and Graham.

During the same year, Santana formed the Santana Blues Band, with fellow street musicians, David Brown and Gregg Rolie (bassist and keyboard player, respectively).mWith their highly original blend of Latin-infused rock, jazz, blues, salsa and African rhythms, the band (which quickly adopted their frontman's name, Santana) gained an immediate following on the San Francisco club circuit.

The band's early success, capped off by a memorable performance at Woodstock in 1969, led to him signing a recording contract with Columbia Records, then run by Clive Davis.

Said Santana of the 1960’s: “The '60s were a leap in human consciousness. Mahatma Gandhi, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Che Guevara, Mother Teresa, they led a revolution of conscience. The Beatles, The Doors, Jimi Hendrix created revolution and evolution themes. The music was like Dalí, with many colors and revolutionary ways. The youth of today must go there to find themselves."

Here, Santana recalls his classic performance at Woodstock in 1969 and then performs “Soul Sacrifice.”

Bob Dylan’s "Like a Rolling Stone" was released as a single by Columbia Records on this day in 1965 — 58 years ago today.

The song was written by Dylan in June, 1965 in confrontational lyrics after he returned exhausted from a grueling tour of England. Dylan distilled this long draft into four verses and a chorus.

"Like a Rolling Stone" was recorded a few weeks later as part of the sessions for the forthcoming album, Highway 61 Revisited. It was take #4 recorded on June 16 that Dylan selected for release.

During a difficult two-day preproduction, Dylan struggled to find the essence of the song, which was demoed without success in 3/4 time. A breakthrough was made when it was tried in a rock music format, and rookie session musician, Al Kooper, improvised the organ riff for which the track is known.

However, Columbia Records was unhappy with both the song's length at over six minutes and its heavy electric sound, and was hesitant to release it. It was only when a month later a copy was leaked to a new popular music club and heard by influential DJs that the song was put out as a single.

Although radio stations were reluctant to play such a long track, "Like a Rolling Stone" reached #2 in the U.S. Billboard charts (#1 in Cashbox) and became a worldwide hit. Critics have described the track as revolutionary in its combination of different musical elements including the youthful, cynical sound of Dylan's voice and the directness of the question, "How does it feel?"

"Like a Rolling Stone" transformed Dylan's image from folk singer to rock star, and is considered one of the most influential compositions in postwar popular music. The song has been covered by numerous artists, from The Jimi Hendrix Experience and The Rolling Stones to The Wailers and Green Day.

At an auction two years ago, Dylan's handwritten lyrics to the song fetched $2 million — a world record for a popular music manuscript.

Dylan performed the song live for the first time within days of its release, when he appeared at the Newport Folk Festival on July 25, 1965 in Newport, Rhode Island. Many of the audience's folk enthusiasts objected to Dylan's use of electric guitars, looking down on rock 'n roll. The folkies, as guitarist Mike Bloomfield put it, thought of the song as popular amongst "greasers, heads, dancers, people who got drunk and boogied."

According to Dylan's friend, music critic Paul Nelson, "The audience [was] booing and yelling 'Get rid of the electric guitar'," while Dylan and his backing musicians gave an uncertain rendition of their new single.

Highway 61 Revisited was issued at the end of August, 1965. When Dylan went on tour that fall, he asked Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm, future members of The Band, to join Al Kooper and Harvey Brooks, to accompany him in performing the electric half of the concerts.

"Like a Rolling Stone" took the closing slot on his setlist and held it, with rare exceptions, through the end of his 1966 "world tour."

On May 17, 1966, during the last leg of the tour, Dylan and his band performed at Free Trade Hall in Manchester, England. Just before they started to play the track, an audience member yelled "Judas!," apparently referring to Dylan's supposed "betrayal" of folk music.

Dylan responded, "I don't believe you. You're a liar!" With that, he turned to the band, ordering them to "play it fucking loud."

Since then, "Like a Rolling Stone" has remained a staple in Dylan's concerts, often with revised arrangements. It was included in his 1969 Isle of Wight show and in both his reunion tour with The Band in 1974 and the Rolling Thunder Revue tour in 1975–76. The song continued to be featured in other tours throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

On the Never Ending Tour, which began in 1988 and continues today, "Like a Rolling Stone" has been one of the five most performed songs, with 653 performances registered through 2005.

Bob Dylan and crew listen to the final recording of "Like a Rolling Stone" in the summer of 1965.

On the left, turning to his left, is producer Tom Wilson. In the middle back is Albert Grossman. On the right is Bob Dylan with his friend, Danny Kalb.

Kalb said he was invited to the studio by Dylan that day to listen to the recording.

On this day in 1933 — 90 years ago — best-selling novelist Cormac McCarthy, whose books include “All the Pretty Horses,” “No Country for Old Men” and “The Road,” which won the Pulitzer Prize, was born in Providence, Rhode Island.

McCarthy’s novels, often set in the American Southwest, are known for being bleak and violent and often feature characters who are outsiders or criminals.

McCarthy, whose father was a lawyer, was raised in Tennessee and attended the University of Tennessee in the early 1950s. He dropped out of school in 1953 to serve for four years in the U.S. Air Force then returned to the university before leaving again without graduating.

McCarthy’s first novel, “The Orchard Keeper,” was published in 1965 and edited (along with several of his later novels) by Albert Erskine, the longtime editor for William Faulkner, to whom McCarthy has been compared.

During the 1960s and 1970s, McCarthy lived an impoverished existence as his next novels — “Outer Dark,” “Child of God” and “Suttree” — were each published to modest sales.

In 1985, he released “Blood Meridian: Or the Evening Redness in the West,” about a violent gang of mercenaries hunting Indians on the Texas-Mexico border in the mid-19th century. Time magazine later named “Blood Meridian” to its list of 100 best English-language novels published between 1923 and 2005.

McCarthy’s commercial breakthrough came with 1992’s “All the Pretty Horses,” about the adventures of a young Texas cowboy and his friend who travel to Mexico in the mid-20th century. A best-seller, “All the Pretty Horses” won the National Book Award and was turned into a 2000 movie directed by Billy Bob Thornton and starring Matt Damon and Penelope Cruz.

The novel was the first book in McCarthy’s Border trilogy, which includes “The Crossing” (1994) and “Cities of the Plain” (1998).

“No Country for Old Men,” about a serial killer and a drug deal that goes wrong, debuted in 2005. The book was made into a 2007 feature film directed by Ethan and Joel Coen and starring Josh Brolin, Javier Bardem and Tommy Lee Jones. It won four Academy Awards, including best picture.

In 2006, “The Road,” about a father and son who journey across a post-apocalyptic wasteland, was published. The novel won numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize.

In 2007, the famously reclusive McCarthy gave his first-ever television interview to Oprah Winfrey after she selected “The Road” for her on-air book club. In 2009, a big-screen adaptation of “The Road,” featuring Viggo Mortensen, was released.

That same year, McCarthy auctioned off the manual typewriter on which he’d written all his novels. The machine, which he bought at a Tennessee pawn shop in 1963 for $50, sold for $254,500.

The author donated the proceeds to the Santa Fe Institute, a scientific think tank. A friend gave McCarthy a replacement typewriter of the same model, reportedly purchased for less than $20.

McCarthy died at his home in Santa Fe on June 13, 2023, at the age of 89.

On this death, Stephen King said McCarthy was "maybe the greatest American novelist of my time ... He was full of years and created a fine body of work, but I still mourn his passing."

Gary Graver, Oja Kodar and Orson Welles on the set of The Other Side of the Wind

Photo by Frank Marshall

Gary Graver, Orson Welles’ last cameraman, was born 85 years ago today.

Graver was a prolific filmmaker who specialized in low-cost “B” movie production and also directed adult films under the pseudonym, Robert McCallum.

At age 20, he moved to Hollywood to become an actor, but drifted into production when acting work was scarce.

In 1970, Graver made an unannounced call on Orson Welles, saying he wanted to work with the director. Welles told Graver that only one other person had ever called him to say they wanted to work with him —and that was Gregg Toland, who worked with Welles on “Citizen Kane.”

Graver shot one of Welles’ best films, the documentary, “F for Fake.” He also shot “Filming Othello,” and worked for years on the long and meandering unfinished project, “The Other Side of the Wind.”

Graver's work for Welles was unpaid, and during the shooting of one scene in “The Other Side of the Wind,” Welles used as a prop his 1941 Oscar that he won as the co-writer of “Citizen Kane.” When shooting was finished, he handed the statuette to Graver saying, "Here, keep this."

Graver understood this to be a gift in lieu of payment for his work. Graver held onto the award for several years until he ran into financial trouble in the 1990s, and in 1994 he sold it for $50,000. The purchaser, a company called Bay Holdings, then attempted to sell it at auction through Sotheby's in London.

When Welles' daughter, Beatrice Welles, learned of the intended sale, she successfully sued both Graver and the holding company to stop the sale. She eventually took possession of the statuette before then selling it herself.

Graver’s work in the adult film industry resulted in more than 135 films including “Unthinkable,” which won the AVN Award for Best All-Sex Video in 1985. He was later inducted into the AVN Hall of Fame for his work.

After meeting Welles in early 1985, one of the first people he introduced me to was Graver. He asked me to teach Graver to use a Betacam. Graver told me about his adult films and wanted to use a Betacam to try on one.

With the understanding I would let him use the camera to learn for work with Orson, I loaned a Betacam to Graver. He loved it and so did the entire adult film industry, which previously had used only 16mm film.

The project Graver shot with my camera heralded the permanent move of adult films to video. Graver told me I had a hand in starting something big in adult films. It wasn’t exactly what I had in mind in helping Orson Welles.

A couple of weeks after Orson’s death, Graver came by my office for a visit. He said something I will never forget. “I’ve been driving around for two weeks with Orson’s ashes in the trunk of my car,” Graver said in a matter of fact way.

“What?,” I responded, quickly envisioning a fender bender with the great man’s ashes being scattered across an LA freeway.

“I’m not going to take them into my house,” Graver said, almost fearing the prospect.

“What should I do?”

I thought for a minute, looked a Graver, and said,

“I don’t know.”

Graver died on November 16, 2006 at his home in Rancho Mirage, California after a lengthy battle with cancer.

Orson Welles’ ashes, by the way, were finally scattered in Spain on a bullfighter’s ranch.

Natalie Wood was born 85 years ago today.

A film and television actress, Wood was best known for her screen roles in Miracle on 34th Street, Splendor in the Grass, Rebel Without a Cause and West Side Story.

After first working in films as a child, Wood became a successful Hollywood star as a young adult, receiving three Academy Award nominations before she was 25 years old. She began acting in movies at the age of four. At age eight, she was given a co-starring role in the classic Christmas film, Miracle on 34th Street.

As a teenager, her performance in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) earned her a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. She starred in the musical films, West Side Story (1961) and Gypsy (1962), and received Academy Award for Best Actress nominations for her performances in Splendor in the Grass (1961) and Love with the Proper Stranger (1963). Her career continued with films such as Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice in 1969.

After this she took a break from acting and had two children, appearing in only two theatrical films during the 1970s. She was married to actor Robert Wagner twice, and to producer Richard Gregson in between her marriages to Wagner.

She had one daughter by each: Natasha Gregson Wagner and Courtney Wagner. Her younger sister, Lana Wood, is also an actress. Wood starred in several television productions, including a remake of the film, From Here to Eternity (1979), for which she won a Golden Globe Award.

During her career, from child actress to adult star, her films represented a "coming of age" for both her and Hollywood films in general.

At age 43, Wood drowned near Santa Catalina Island, California at the time her last film, Brainstorm (1983), was in production with co-star, Christopher Walken. Her death was declared an accident for 31 years. In 2012, after a new investigation, the cause was reclassified as "undetermined."

Accordion Girl, 1953

Photo by Robert Doisneau