Father of photojournalism - Henri Cartier-Bresson - was born 115 years ago today

Henri Cartier-Bresson was born 115 years ago today.

A French photographer considered to be the father of modern photojournalism, Cartier-Bresson was an early adopter of 35mm format and the master of candid photography.

Cartier-Bresson helped develop the street photography or life reportage style that was coined “The Decisive Moment.” It has influenced generations of photographers who followed.

He was born in Chanteloup-en-Brie, Seine-et-Marne, France, the oldest of five children. His father was a wealthy textile manufacturer, whose Cartier-Bresson thread was a staple of French sewing kits. His mother's family were cotton merchants and landowners from Normandy, where he spent part of his childhood.

The Cartier-Bresson family lived in a bourgeois neighborhood in Paris, near Le Pont de l'Europe (the Europe Bridge), the point where six major avenues crossed, leading out in all directions: the Rue de Berne, the Rue de St. Petersbourg, the Rue de Constantinople, the Rue de Madrid, the Rue de Vienne (Vienna), the Rue de Londres (London) and the Rue de Berlin.

His parents were able to provide him with financial support to develop his interests in photography in a more independent manner than many of his contemporaries. Cartier-Bresson also sketched in his spare time.

As a young boy, Cartier-Bresson owned a Box Brownie, using it for taking holiday snapshots. He later experimented with a 3×4-inch view camera.

In 1927, at the age of 20, Cartier-Bresson entered a private art school and the Lhote Academy, the Parisian studio of the Cubist painter and sculptor, André Lhote. The ambition of Lhote was to integrate the Cubists' approach to reality with classical artistic forms. He wanted to link the French classical tradition of Nicolas Poussin and Jacques-Louis David to Modernism.

Cartier-Bresson also studied painting with society portraitist, Jacques Émile Blanche. During this period, he read Dostoevsky, Schopenhauer, Rimbaud, Nietzsche, Mallarmé, Freud, Proust, Joyce, Hegel, Engels and Marx. Lhote took his pupils to the Louvre to study classical artists and to Parisian galleries to study contemporary art.

Cartier-Bresson's interest in modern art was combined with an admiration for the works of the Renaissance — of masterpieces by Jan van Eyck, Paolo Uccello, Masaccio and Piero della Francesca. Cartier-Bresson often regarded Lhote as his teacher of "photography without a camera."

Although Cartier-Bresson gradually began to be restless under Lhote's "rule-laden" approach to art, his rigorous theoretical training would later help him to confront and resolve problems of artistic form and composition in photography. In the 1920s, schools of photographic realism were popping up throughout Europe, but each had a different view on the direction photography should take.

The photography revolution had begun: "Crush tradition! Photograph things as they are!" The Surrealist movement, founded in 1924, was a catalyst for this paradigm shift. Cartier-Bresson began socializing with the Surrealists at the Café Cyrano, in the Place Blanche. He met a number of the movement's leading protagonists, and was particularly drawn to the Surrealist movement's linking of the subconscious and the immediate to their work.

The historian Peter Galassi explained: “The Surrealists approached photography in the same way that Aragon and Breton...approached the street: with a voracious appetite for the usual and unusual...The Surrealists recognized in plain photographic fact an essential quality that had been excluded from prior theories of photographic realism. They saw that ordinary photographs, especially when uprooted from their practical functions, contain a wealth of unintended, unpredictable meanings.”

Cartier-Bresson matured artistically in this stormy cultural and political environment. He was aware of the concepts and theories mentioned, but could not find a way of expressing this imaginatively in his paintings. He was very frustrated with his experiments and subsequently destroyed the majority of his early works.

From 1928 to 1929, Cartier-Bresson attended the University of Cambridge, where he studied English, art and literature and became bilingual. In 1930, stationed at Le Bourget, near Paris, he completed his mandatory service in the French Army. He remembered, "And I had quite a hard time of it, too, because I was toting Joyce under my arm and a Lebel rifle on my shoulder."

In 1929, Cartier-Bresson's air squadron commandant placed him under house arrest for hunting without a license. He met American expatriate, Harry Crosby, at Le Bourget, who persuaded the officer to release Cartier-Bresson into his custody for a few days.

Finding their mutual interest in photography, and they spent their time together taking and printing pictures at Crosby's home, Le Moulin du Soleil (The Sun Mill), near Paris in Ermenonville, France. Crosby later said Cartier-Bresson "looked like a fledgling, shy and frail, and mild as whey."

Embracing the open sexuality offered by Crosby and his wife, Caresse, Cartier-Bresson fell into an intense sexual relationship with her. Two years after Harry Crosby committed suicide, Cartier-Bresson's affair with Caresse Crosby ended in 1931, leaving him broken hearted.

During his enlistment, he had read Conrad's Heart of Darkness, and decided to seek escape and adventure on the Côte d'Ivoire in French colonial Africa. About abandoning painting, he wrote, "I left Lhote's studio because I did not want to enter into that systematic spirit. I wanted to be myself. To paint and to change the world counted for more than everything in my life."

Cartier-Bresson was finally brought to photography by the work of Munkacsi. When I saw the photograph of Munkacsi of the black kids running in a wave I couldn't believe such a thing could be caught with the camera. I said damn it, I took my camera and went out into the street."

That photograph inspired him to stop painting and to take up photography seriously. He explained, "I suddenly understood that a photograph could fix eternity in an instant."

He acquired the Leica camera with 50mm lens in Marseilles that would accompany him for many years. He described the Leica as an extension of his eye. The anonymity that the small camera gave him in a crowd or during an intimate moment was essential in overcoming the formal and unnatural behavior of those who were aware of being photographed.

He enhanced his anonymity by painting all shiny parts of the Leica with black paint. The Leica opened up new possibilities in photography — the ability to capture the world in its actual state of movement and transformation. He said, "I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, ready to 'trap' life."

Restless, he photographed in Berlin, Brussels, Warsaw, Prague, Budapest and Madrid. His photographs were first exhibited at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1932, and subsequently at the Ateneo Club in Madrid.

In 1934 in Mexico, he shared an exhibition with Manuel Alvarez Bravo. In the beginning, he did not photograph much in his native France. It would be years before he photographed there extensively.

Cartier-Bresson traveled to the United States in 1935 with an invitation to exhibit his work at New York's Julien Levy Gallery. He shared display space with fellow photographers Walker Evans and Manuel Alvarez Bravo.

Carmel Snow of Harper's Bazaar, gave him a fashion assignment, but he fared poorly since he had no idea how to direct or interact with the models. Nevertheless, Snow was the first American editor to publish Cartier-Bresson's photographs in a magazine.

While in New York, he met photographer Paul Strand, who did camerawork for the Depression-era documentary, “The Plow That Broke the Plains.” When he returned to France, Cartier-Bresson applied for a job with renowned French film director, Jean Renoir. He acted in Renoir's 1936 film Partie de campagne and in the 1939 La Règle du jeu, for which he played a butler and served as second assistant.

Renoir made Cartier-Bresson act so he could understand how it felt to be on the other side of the camera. Cartier-Bresson also helped Renoir make a film for the Communist party on the 200 families, including his own, who ran France. During the Spanish civil war, Cartier-Bresson co-directed an anti-fascist film with Herbert Kline, to promote the Republican medical services.

Cartier-Bresson's first photojournalist photos to be published came in 1937 when he covered the coronation of King George VI, for the French weekly, Regards. He focused on the new monarch's adoring subjects lining the London streets, and took no pictures of the king. His photo credit read, "Cartier," as he was hesitant to use his full family name.

In the spring of 1947, Cartier-Bresson, with Robert Capa, David Seymour, William Vandivert and George Rodger founded Magnum Photos. Capa's brainchild, Magnum, was a cooperative picture agency owned by its members. The team split photo assignments among the members. Cartier-Bresson would be assigned to India and China.

Cartier-Bresson achieved international recognition for his coverage of Gandhi's funeral in India in 1948 and the last (1949) stage of the Chinese Civil War. He covered the last six months of the Kuomintang administration and the first six months of the Maoist People's Republic. He also photographed the last surviving Imperial eunuchs in Beijing, as the city was falling to the communists.

In 1952, Cartier-Bresson published his book, Images à la sauvette, whose English edition was titled, The Decisive Moment. It included a portfolio of 126 of his photos from the East and the West. The book's cover was drawn by Henri Matisse.

For his 4,500-word philosophical preface, Cartier-Bresson took his keynote text from Cardinal de Retz of the 17th century. Translated it reads: "To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression."

In in interview with the Washington Post in 1957, Cartier-Bresson said:

"Photography is not like painting. There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative. Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever."

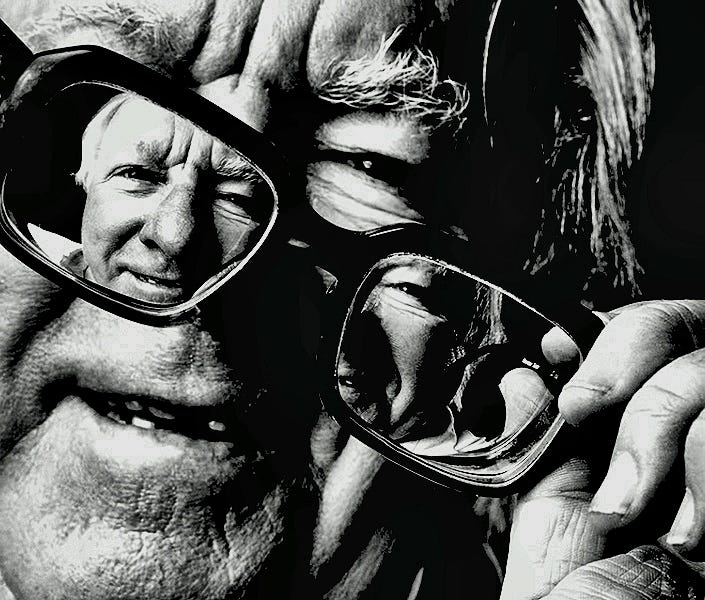

Cartier-Bresson died in Montjustin (Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France) on August 3, 2004 at age 95. He was a photographer who hated to be photographed and treasured his privacy above all. Photographs of Cartier-Bresson do exist, but they are scant.

Cartier-Bresson almost exclusively used Leica 35mm rangefinder cameras equipped with normal 50 mm lenses or occasionally a wide-angle for landscapes. He never photographed with flash, a practice he saw as "[i]mpolite...like coming to a concert with a pistol in your hand." He worked exclusively in black and white.

He disliked developing or making his own prints and showed a considerable lack of interest in the process of photography in general, likening photography with the small camera to an "instant drawing." The technical aspects of photography were valid for him only where they allowed him to express what he saw:

“The camera for us is a tool, not a pretty mechanical toy. In the precise functioning of the mechanical object perhaps there is an unconscious compensation for the anxieties and uncertainties of daily endeavor. In any case, people think far too much about techniques and not enough about seeing.”

Fisherman, Colombia, 1945

Photo by Henri Cartier-Bresson

John Lee Hooker

Photo by Robert Knight

It’s the birthday of John Lee Hooker, highly influential blues singer-songwriter and guitarist.

The year of Hooker’s birth is in dispute. Most official sources list 1917, though at times Hooker stated he was born in 1920. Information found in the 1920 and 1930 censuses indicates that he was probably born in 1912.

Hooker began his life as the son of a sharecropper, William Hooker, and rose to prominence performing his own unique style of what was originally a unique brand of country blues.

He developed a "talking blues" style that was his trademark. Though similar to the early Delta blues, his music was metrically free.

Hooker embodied his own unique genre of the blues, often incorporating the boogie-woogie piano style and a driving rhythm into his blues guitar playing and singing.

His best known songs include "Boogie Chillen'" (1948), "I'm in the Mood" (1951) and "Boom Boom" (1962), the first two reaching R&B #1 in the Billboard charts.

There is some debate as to the year of Hooker's birth in Coahoma County, Mississippi. But according to his official website, he was born on August 22, 1917. However, information in the 1920 and 1930 censuses indicates that he was born in 1912.

Hooker and his siblings were home-schooled. They were permitted to listen only to religious songs, with his earliest exposure being the spirituals sung in church.

In 1921, his parents separated. The next year, his mother married William Moore, a blues singer who provided Hooker with his first introduction to the guitar (and whom John would later credit for his distinctive playing style).

John's stepfather was his first outstanding blues influence. William Moore was a local blues guitarist who learned in Shreveport, Louisiana to play a droning, one-chord blues that was strikingly different from the Delta blues of the time. Around 1923, his natural father died.

At the age of 15, Hooker ran away from home, reportedly never seeing his mother or stepfather again. Throughout the 1930s, he lived in Memphis where he worked on Beale Street at The New Daisy Theatre and occasionally performed at house parties.

He worked in factories in various cities during World War II, drifting until he found himself in Detroit in 1948 working at Ford Motor Company.

Hooker felt right at home near the blues venues and saloons on Hastings Street, the heart of black entertainment on Detroit's east side. In a city noted for its pianists, guitar players were scarce.

Performing in Detroit clubs, his popularity grew quickly and, seeking a louder instrument than his crude acoustic guitar, he bought his first electric guitar.

Hooker's recording career began in 1948 when his agent placed a demo, made by Hooker, with the Bihari brothers, owners of the Modern Records label. The company initially released an up-tempo number, "Boogie Chillen’,” which became Hooker's first hit single.

Though they were not songwriters, the Biharis often purchased or claimed co-authorship of songs that appeared on their labels, thus securing songwriting royalties for themselves, in addition to their own streams of income.

Despite being illiterate, Hooker was a prolific lyricist. In addition to adapting the occasionally traditional blues lyric (such as "if I was chief of police, I would run her right out of town"), he freely invented many of his songs from scratch.

Recording studios in the 1950s rarely paid black musicians more than a pittance, so Hooker would spend the night wandering from studio to studio, coming up with new songs or variations on his songs for each studio.

Because of his recording contract, he would record these songs under obvious pseudonyms such as John Lee Booker, notably for Chess Records and Chance Records in 1951/52, as Johnny Lee for De Luxe Records in 1953/54 as John Lee, and even, John Lee Cooker, or as Texas Slim, Delta John, Birmingham Sam and his Magic Guitar, Johnny Williams or The Boogie Man.

In 1989, he joined with a number of musicians, including Carlos Santana and Bonnie Raitt, to record The Healer.

Hooker recorded several songs with Van Morrison, including "Never Get Out of These Blues Alive,” "The Healing Game" and "I Cover the Waterfront.”

He also appeared on stage with Van Morrison several times, some of which was released on the live album, A Night in San Francisco. The same year he appeared as the title character on Pete Townshend's, The Iron Man: A Musical.

Hooker recorded over 100 albums. He lived the last years of his life in Long Beach, California.

In 1997, he opened a nightclub in San Francisco's Fillmore District called "John Lee Hooker's Boom Boom Room,” after one of his hits.

He fell ill just before a tour of Europe in 2001 and died on June 21 at the age of 83, two months before his 84th birthday.

Here, Hooker performs “Boom Boom” from a Blues Brothers film.

Dorothy Parker was born 130 years ago today.

Parker was an American poet, short story writer, critic and satirist, best known for her wit, wisecracks and eye for 20th Century urban foibles.

From a conflicted and unhappy childhood, Parker rose to acclaim — both for her literary output in such venues as The New Yorker and as a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table. Following the breakup of the circle, Parker traveled to Hollywood to pursue screenwriting.

Her successes there, including two Academy Award nominations, were curtailed as her involvement in left wing politics led to a place on the Hollywood blacklist. Dismissive of her own talents, she deplored her reputation as a "wisecracker." Nevertheless, her literary output and reputation for her sharp wit have endured.

Also known as Dot or Dottie, Parker was born Dorothy Rothschild to Jacob Henry and Eliza Annie Rothschild at 732 Ocean Avenue in Long Branch, New Jersey, where her parents had a summer beach cottage.

Parker wrote in her essay, "My Hometown," that her parents got her back to their Manhattan apartment shortly after Labor Day so she could be called a true New Yorker.

She grew up on the Upper West Side and attended Roman Catholic elementary school at the Convent of the Blessed Sacrament on West 79th Street with sister Helen, despite having a Jewish father and Protestant stepmother. Parker once joked that she was asked to leave following her characterization of the Immaculate Conception as "spontaneous combustion."

Parker sold her first poem to Vanity Fair magazine in 1914 and, some months later, was hired as an editorial assistant for another Condé Nast magazine, Vogue. She moved to Vanity Fair as a staff writer after two years at Vogue.

In 1917, she met and married a Wall Street stockbroker, Edwin Pond Parker II, but they were separated by his army service in World War I. She had ambivalent feelings about her Jewish heritage given the strong antisemitism of that era and joked that she married to escape her name.

Her career took off while she was writing theatre criticism for Vanity Fair, which she began to do in 1918 as a stand-in for the vacationing P. G. Wodehouse. At the magazine, she met Robert Benchley, who became a close friend, and Robert E. Sherwood. The trio began lunching at the Algonquin Hotel on a near-daily basis and became founding members of the Algonquin Round Table.

The Round Table numbered among its members the newspaper columnists Franklin Pierce Adams and Alexander Woollcott. Through their re-printing of her lunchtime remarks and short verses, particularly in Adams' column, "The Conning Tower,” Dorothy began developing a national reputation as a wit.

One of her most famous comments was made when the group was informed that former president Calvin Coolidge had died. Parker remarked, "How could they tell?" Parker's caustic wit as a critic initially proved popular, but she was eventually terminated by Vanity Fair in 1920 after her criticisms began to offend powerful producers too often.

In solidarity, both Benchley and Sherwood resigned in protest. When Harold Ross founded The New Yorker in 1925, Parker and Benchley were part of a "board of editors" established by Ross to allay concerns of his investors.

Parker's first piece for the magazine appeared in its second issue. Parker became famous for her short, viciously humorous poems, many about the perceived ludicrousness of her many (largely unsuccessful) romantic affairs and others wistfully considering the appeal of suicide. The next 15 years were Parker's greatest period of productivity and success.

In the 1920s alone, she published some 300 poems and free verses in Vanity Fair, Vogue, "The Conning Tower" and The New Yorker as well as Life, McCall's and The New Republic.

Parker died on June 7, 1967 of a heart attack at the age of 73.

In her will, she bequeathed her estate to the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. foundation. Following King's death, her estate was passed on to the NAACP. Her executor, Lillian Hellman, bitterly but unsuccessfully contested this disposition. Her ashes remained unclaimed in various places, including her attorney Paul O'Dwyer's filing cabinet, for approximately 17 years.

In 1988, the NAACP claimed Parker's remains and designed a memorial garden for them outside their Baltimore headquarters. The plaque reads:

Here lie the ashes of Dorothy Parker (1893–1967) humorist, writer, critic. Defender of human and civil rights.

For her epitaph she suggested, “Excuse my dust.”

Ray Bradbury was born 103 years ago today.

A fantasy, science fiction, horror and mystery fiction author, Bradbury was wrote the dystopian novel, Fahrenheit 451, in 1953. His science fiction and horror stories are gathered together as The Martian Chronicles (1950) and The Illustrated Man (1951).

Bradbury was one of the most celebrated 20th and 21st century American genre writers. He wrote and consulted on many screenplays and television scripts, including Moby Dick and It Came from Outer Space. Many of his works have been adapted into comic books, television shows and films.

Bradbury died in Los Angeles on June 5, 2012 at the age of 91.

Honor Blackman, actress who played “Pussy Galore” in the 1964 James Bond film, Goldfinger, was born 98 years ago today.

Blackman was an English actress, is also widely known for the roles of Cathy Gale in The Avengers (1962–64), Julia Daggett in Shalako (1968) and Hera in Jason and the Argonauts (1963).

Born in Plaistow, London E13, Blackman’s father, Frederick, was a statistician. She attended North Ealing Primary School and Ealing County Grammar School for Girls. For her 15th birthday, her parents gave her acting lessons and she started training at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in 1940. While attending the Guildhall School, Blackman worked as a clerical assistant for the Home Office.

Blackman's film debut was a nonspeaking part in, Fame Is the Spur (1947). Other films include Quartet (1948), based on short stories by W. Somerset Maugham; So Long at the Fair (1950), in which she appeared with Dirk Bogarde; A Night to Remember (1958), an account of the RMS Titanic; the comedy, The Square Peg (1958); Life at the Top (1965) with Laurence Harvey; The Virgin and the Gypsy (1970); and the Western films, Shalako (1968) with Sean Connery and Brigitte Bardot, and Something Big (1971) with Dean Martin.

Blackman played Hera in Jason and the Argonauts (1963), which is well known for the stop-motion animation and effects of Ray Harryhausen. She had roles in the films, Bridget Jones's Diary (2001), and, Jack Brown and the Curse of the Crown, also in 2001.

Albert R. Broccoli said that Blackman was cast opposite Sean Connery in the James Bond films based on her success in the British TV series, The Avengers. He knew that most American audiences would not have seen the program. "The Brits would love her because they knew her as Mrs. Gale, the Yanks would like her because she was so good, it was a perfect combination," Broccoli said.

During the 1960s, Blackman practiced judo at the famous Budokwai dojo. This helped her prepare for her roles as Cathy Gale in The Avengers and Pussy Galore in Goldfinger. At 38, she was one of the oldest actresses to play a Bond girl.

In 1981, Blackman appeared in the London revival of The Sound of Music, opposite Petula Clark. The production opened to rave reviews and the largest advance sale in British theatre history to that time. She spent most of 1987 at the Fortune Theatre starring as the Mother Superior in the West End production of Nunsense.

Blackman returned to the theatre in 2005, touring through 2006 with a production of My Fair Lady, in which she played Mrs. Higgins.

She developed a one-woman show, Word of Honor, which premiered in October, 2006.

Blackman died at her home in Lewes, East Sussex, on April 5, 2020, aged 94, from natural causes.

Here, Blackman as Pussy Galore in Goldfinger, 1964.

People in the Sun, 1960

Painting by Edward Hopper