Dave Van Ronk, folk musician nicknamed the "Mayor of MacDougal Street," was born 87 years ago today

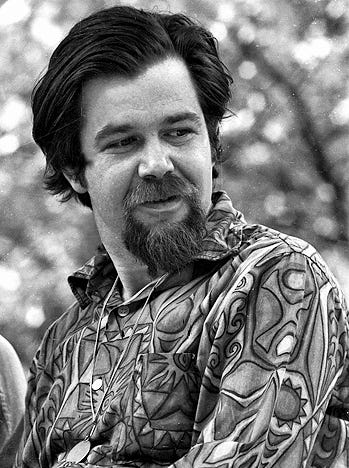

Dave Van Ronk, 1968 Philadelphia Folk Festival

Dave Van Ronk was born 87 years ago today.

Van Ronk was a folk singer, born in Brooklyn, who settled in Greenwich Village. He was eventually nicknamed the "Mayor of MacDougal Street."

An important figure in the acoustic folk revival of the 1960s, Van Ronk’s work ranged from old English ballads to Bertolt Brecht, blues, gospel, rock, New Orleans jazz and swing. He was also known for performing instrumental ragtime guitar music, especially his transcription of St. Louis Tickle and Scott Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag.

Van Ronk was a widely admired avuncular figure in the Village, presiding over the coffeehouse folk culture and acting as a friend to many up-and-coming artists by inspiring, assisting and promoting them. Folk performers whom he befriended include Bob Dylan, Tom Paxton, Patrick Sky, Phil Ochs, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Guthrie Thomas and Joni Mitchell.

Van Ronk received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in December, 1997. His first professional gigs were with various traditional jazz bands around New York, of which he later observed: "We wanted to play traditional jazz in the worst way… and we did!"

But the jazz revival did not take off, and Van Ronk turned to performing blues. He enjoyed and been influenced by artists like Furry Lewis and Mississippi John Hurt. Van Ronk was not the first white musician to perform African-American blues, but became noted for his interpretation of it in its original context.

By about 1958, he was firmly committed to the folk-blues style, accompanying himself with his own acoustic guitar. He performed blues, jazz and folk music, occasionally writing his own songs, but generally arranging the work of earlier artists and his folk revival peers.

He became noted both for his large physical stature and his expansive charisma, which bespoke an intellectual, cultured gentleman of many talents. Among his many interests were cooking, science fiction (he was active for some time in science fiction fandom — referring to it as "mind rot" — and contributed to fanzines), world history and politics.

During the 1960s, he supported radical left-wing political causes and was a member of the Libertarian League and the Trotskyist American Committee for the Fourth International (ACFI, later renamed the Workers League, predecessor to the Socialist Equality Party).

Attracted to the commotion from a neighboring bar, and no stranger to police violence, he was at the famous Stonewall Riots in 1969 during which he was grabbed by police, arrested, briefly jailed and charged with felony assault on a police officer.

In 1974, he appeared at "An Evening For Salvador Allende," a concert organized by Phil Ochs, alongside such other performers as his old friend, Bob Dylan. The concert protested the overthrow of the democratic socialist government of Chile and aided refugees from the U.S.-backed military junta led by Augusto Pinochet.

After Ochs's suicide in 1976, Van Ronk joined the many performers who played at his memorial concert in the Felt Forum at Madison Square Garden, playing his bluesy version of the traditional folk ballad, "He Was A Friend Of Mine.”

In 2000, he performed at Blind Willie's in Atlanta, clothed in garish Hawaiian garb, speaking fondly of his impending return to Greenwich Village. He reminisced over tunes like "You've Been a Good Old Wagon," a song teasing a worn-out lover, which he ruefully remarked had seemed humorous to him back in 1962.

He was married to Terri Thal in the 1960s, lived for many years with Joanne Grace, then married Andrea Vuocolo, with whom he spent the rest of his life. He continued to perform for four decades and gave his last concert just a few months before his death.

Van Ronk died in a New York hospital of cardiopulmonary failure while undergoing postoperative treatment for colon cancer. He died before completing work on his memoirs, which were finished by his collaborator, Elijah Wald, and published in 2005 as The Mayor Of MacDougal Street.

Van Ronk was underestimated as a musician and blues guitarist. His guitar work is noteworthy for both syncopation and precision. In its simplest form, it shows similarities to Mississippi John Hurt. But Van Ronk's main influence was the Reverend Gary Davis, who conceived the guitar as "a piano around his neck."

Van Ronk took this pianistic approach and added a harmonic sophistication adapted from the band voicings of Jelly Roll Morton and Duke Ellington. He ranks high in bringing blues style to Greenwich Village during the 1960s, as well as introducing the folk world to the complex harmonies of Kurt Weill in his many Brecht-Weill interpretations.

He was one of the very few hardcore traditional revivalists to move with the times. He brought old blues and ballads together with the new sounds of Dylan, Mitchell and Leonard Cohen. During this crucial period, he performed with Dylan and spent many years teaching guitar in Greenwich Village, including to Christine Lavin, David Massengill, Terre Roche and Suzzy Roche.

He influenced his protégé, Danny Kalb, and The Blues Project. The Japanese singer, Masato Tomobe, pop-folk singer Geoff Thais, and the musician and writer, Elijah Wald, learned from him as well.

Van Ronk died on Feb. 10, 2002 before completing work on his memoirs, which were finished by his collaborator, Elijah Wald, and published in 2005 as The Mayor Of MacDougal Street.

In 2004, a section of Sheridan Square, where Barrow Street meets Washington Place, was renamed Dave Van Ronk Street in his memory. Van Ronk was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award posthumously by the World Folk Music Association in 2004.

Known for making interesting and memorable observations, he once said "Painting is all about space, and music is all about time."

Here, Van Ronk performs at the Philadelphia Folk Festival in 1981

Suze Rotolo, Terri Thal, Bob Dylan and Dave Van Ronk, 1963

Photo by Jim Marshall

Lena Horne was born 106 years ago today.

An African American singer, actress, dancer and civil rights activist, Horne joined the chorus of the Cotton Club at the age of sixteen and became a nightclub performer before moving to Hollywood, where she had small parts in numerous movies. She had more substantial parts in the films, Cabin in the Sky and Stormy Weather.

Due to the Red Scare and her left-leaning political views, Horne found herself blacklisted and unable to get work in Hollywood. Returning to her roots as a nightclub performer, Horne took part in the March on Washington in August, 1963, and continued to work as a performer, both in nightclubs and on television, while releasing well-received record albums.

She announced her retirement in March, 1980, but the next year starred in a one-woman show, Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music, which ran for more than three hundred performances on Broadway and earned her numerous awards and accolades. She continued recording and performing sporadically into the 1990s, disappearing from the public eye in 2000.

Born in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, Horne was descended from the John C. Calhoun family, both sides of her family were a mixture of European American, Native American and African-American descent, and belonged to the upper stratum of middle-class, well-educated blacks.

Her father, Edwin Fletcher "Teddy" Horne, Jr. (1892–1970), a numbers kingpin in the gambling trade, left the family when she was three and moved to an upper-middle-class black community in the Hill District community of Pittsburgh.

Her mother, Edna Louise Scottron (1895–1985), daughter of inventor, Samuel R. Scottron, was an actress with a black theatre troupe and traveled extensively.

Scottron's maternal grandmother, Amelie Louise Ashton, was a Senegalese slave. Horne was mainly raised by her grandparents, Cora Calhoun and Edwin Horne.

When Horne was five, she was sent to live in Georgia. For several years, she traveled with her mother.

From 1927 to 1929, she lived with her uncle, Frank S. Horne, who was dean of students at Fort Valley Junior Industrial Institute (now part of Fort Valley State University) in Fort Valley, Georgia, and who would later become an adviser to Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

At 18, she moved in with her father in Pittsburgh, staying in the city's Little Harlem for almost five years and learning from native Pittsburghers Billy Strayhorn and Billy Eckstine, among others.

In the fall of 1933, Horne joined the chorus line of the Cotton Club in New York City. In the spring of 1934, she had a featured role in the Cotton Club Parade starring Adelaide Hall, who took Lena under her wing. A few years later, Horne joined Noble Sissle's Orchestra, with which she toured and with whom she recorded her first record release, a 78 rpm single issued by Decca Records.

After she separated from her first husband, Horne toured with bandleader Charlie Barnet in 1940–41, but disliked the travel and left the band to work at the Café Society in New York.

She replaced Dinah Shore as the featured vocalist on NBC's popular jazz series, The Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street. The show's resident maestros, Henry Levine and Paul Laval, recorded with Horne in June, 1941 for RCA Victor.

Horne left the show after only six months to headline a nightclub revue on the West Coast at Slapsy Maxie's. She was replaced by actress Betty Keene of the Keene sisters.

Horne already had two low-budget movies to her credit: a 1938 musical feature called The Duke is Tops (later reissued with Horne's name above the title as The Bronze Venus); and a 1941 two-reel short subject, Boogie Woogie Dream, featuring pianists Pete Johnson and Albert Ammons.

Horne's songs from Boogie Woogie Dream were later released individually as soundies. She was primarily a nightclub performer during this period and it was during a 1942 club engagement in Hollywood at Slapsy Maxie's in which talent scouts approached Horne to work in pictures.

She chose Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and became the first black performer to sign a long-term contract with a major Hollywood studio. She made her debut with MGM in Panama Hattie (1942) and performed the title song of Stormy Weather (1943), based loosely on the life of Adelaide Hall.

She appeared in a number of MGM musicals, most notably Cabin in the Sky (also 1943), but was never featured in a leading role because of her race and the fact that films featuring her had to be re-edited for showing in states where theaters could not show films with black performers.

As a result, most of Horne's film appearances were stand-alone sequences that had no bearing on the rest of the film, so editing caused no disruption to the storyline. A notable exception was the all-black musical, Cabin in the Sky, although one number was cut because it was considered too suggestive by the censors.

By the mid-1950s, Horne was disenchanted with Hollywood and increasingly focused on her nightclub career. She was blacklisted during the 1950s for her political views.

After leaving Hollywood, Horne established herself as one of the premiere nightclub performers of the post-war era. She headlined at clubs and hotels throughout the U.S., Canada and Europe, including the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, the Cocoanut Grove in Los Angeles and the Waldorf-Astoria in New York.

In 1957, a live album — Lena Horne at the Waldorf-Astoria — became the biggest selling record by a female artist in the history of the RCA-Victor label.

In 1958, Horne became the first African American woman to be nominated for a Tony Award for "Best Actress in a Musical" (for her part in the "Calypso" musical Jamaica) which, at Lena's request, featured her longtime friend, Adelaide Hall.

In 1981, she received a Special Tony Award for her one-woman show, Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music, which also played to acclaim at the Adelphi Theatre in London in 1984.

Despite the show's considerable success (Horne still holds the record for the longest-running solo performance in Broadway history), she did not capitalize on the renewed interest in her career by undertaking many new musical projects.

Horne was long involved with the Civil Rights movement. In 1941, she sang and worked with Paul Robeson. During World War II, when entertaining the troops for the USO, she refused to perform "for segregated audiences or for groups in which German POWs were seated in front of African American servicemen.”

She was at an NAACP rally with Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi, the weekend before Evers was assassinated. She also met President John F. Kennedy at the White House two days before he was assassinated.

She was at the March on Washington and spoke and performed on behalf of the NAACP, SNCC and the National Council of Negro Women. She also worked with Eleanor Roosevelt to pass anti-lynching laws.

Horne died on May 9, 2010 in New York City of heart failure.

Here, Horne performs Stormy Weather in 1967

My friend, Jim Gavin, wrote a wonderful book on Lena Horne, called Stormy Weather. On her birthday, here’s a interview with Jim recalling this iconic figure.

Stanley Clarke at the Montreux Jazz Festival, 1980

Photo by Pierre-Yves Vaucher

Stanley Clarke is 72 years old today.

Clarke is a jazz musician and composer known for his innovative and influential work on double bass and electric bass as well as for his numerous film and television scores. He is best known for his work with the fusion band, Return to Forever, and his role as a bandleader in several trios and ensembles.

Born in Philadelphia, Clarke was introduced to the bass as a schoolboy when he arrived late on the day instruments were distributed to students. Acoustic bass was one of the few remaining selections and he took it.

A graduate of Roxborough High School in Philadelphia, he attended the Philadelphia Musical Academy, (which was absorbed into the University of the Arts in 1985) from which he graduated in 1971. He then moved to New York City and began working with famous bandleaders and musicians including Horace Silver, Art Blakey, Dave Brubeck, Dexter Gordon, Gato Barbieri, Joe Henderson, Chick Corea, Pharoah Sanders, Gil Evans and Stan Getz.

During the 1970s, Clarke joined the jazz fusion group, Return to Forever, led by pianist and synth player, Chick Corea. The group became one of the most important fusion groups and released several albums that achieved both mainstream popularity and critical acclaim.

Clarke also started his solo career in the early 1970s and released a number of albums under his own name. His best known solo album is School Days (1976), which, along with Jaco Pastorius's self-titled debut, is one of the most influential solo bass recordings in fusion history.

Here, Clarke performs a bass solo from School Days

Florence Ballard, a founding member of the Supremes, was born 80 years ago today.

Ballard sang on sixteen Top 40 singles with the group — including 10 #1 hits.

After being removed from the Supremes in 1967, Ballard tried an unsuccessful solo career with ABC Records before she was dropped from the label at the end of the decade. She struggled with alcoholism, depression and poverty for three years.

She was making an attempt for a musical comeback when she died of cardiac arrest in February, 1976 at age 32.

Ballard's death was considered by one critic as "one of rock's greatest tragedies.”

Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind, one of the best-selling novels of all time and the basis for a blockbuster 1939 movie, was published on this day in 1936 — 87 years ago.

In 1926, Mitchell was forced to quit her job as a reporter at the Atlanta Journal to recover from a series of physical injuries. With too much time on her hands, she soon grew restless.

Working on a Remington typewriter — a gift from her second husband, John R. Marsh — in their cramped one-bedroom apartment, Mitchell began telling the story of an Atlanta belle named Pansy O'Hara.

In tracing Pansy's tumultuous life from the antebellum South through the Civil War and into the Reconstruction era, Mitchell drew on the tales she had heard from her parents and other relatives, as well as from Confederate war veterans she had met as a young girl. While she was extremely secretive about her work, Mitchell eventually gave the manuscript to Harold Latham, an editor from New York's MacMillan Publishing.

Latham encouraged Mitchell to complete the novel, with one important change: the heroine's name. Mitchell agreed to change it to Scarlett, now one of the most memorable names in the history of literature.

Published in 1936, Gone with the Wind caused a sensation in Atlanta and went on to sell millions of copies in the United States and throughout the world. While the book drew some criticism for its romanticized view of the Old South and its slaveholding elite, its epic tale of war, passion and loss captivated readers far and wide.

By the time Mitchell won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1937, a movie project was already in the works. The film was produced by Hollywood giant David O. Selznick, who paid Mitchell a record-high $50,000 for the film rights to her book.

After testing hundreds of unknowns and big-name stars to play Scarlett, Selznick hired the British actress, Vivien Leigh, only days after filming began. Clark Gable was also on board as Rhett Butler, Scarlett's dashing love interest.

Plagued with problems on set, Gone with the Wind nonetheless became one of the highest-grossing and most acclaimed movies of all time, breaking box office records and winning nine Academy Awards out of 13 nominations. Though she didn't take part in the film adaptation of her book, Mitchell did attend its star-studded premiere in December, 1939 in Atlanta.

She died just 10 years later, after she was struck by a speeding car while crossing Atlanta's Peachtree Street.

Thanks History.com

Lightning strikes the Grand Canyon, August 30, 2013

Photo by Rolf Maeder