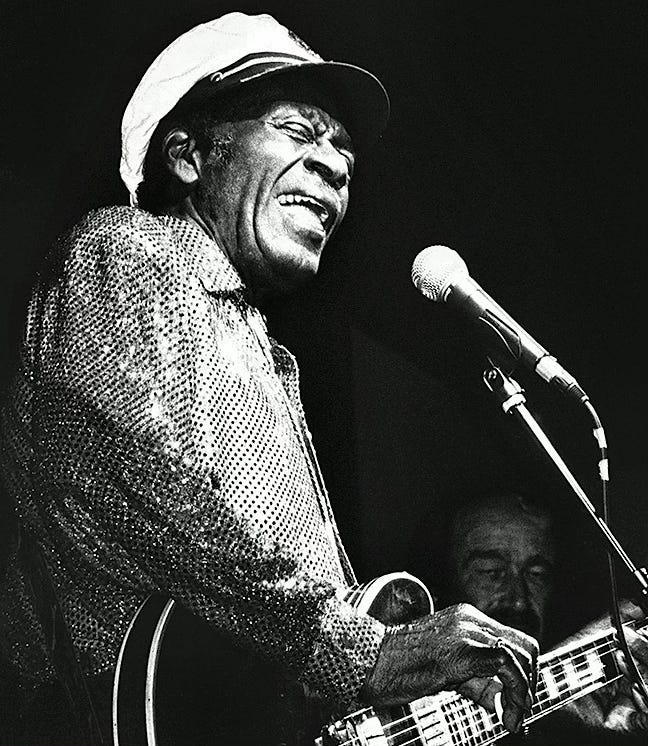

Chuck Berry, pioneer of rock and roll, was born 97 years old today

Chuck Berry, B.B. Kings Club, New York City, June 16, 2006

Photo by Frank Beacham

Chuck Berry, pioneer of rock and roll, was born 97 years old today.

With songs such as "Maybellene" (1955), "Roll Over Beethoven" (1956), "Rock and Roll Music" (1957) and "Johnny B. Goode" (1958), Berry refined and developed rhythm and blues into the major elements that made rock and roll distinctive. His guitar solos and showmanship would be a major influence on subsequent rock music.

Born into a middle-class family in St. Louis, Berry had an interest in music from an early age and gave his first public performance at Sumner High School. While still a high school student, he served a prison sentence for armed robbery between 1944 and 1947. On his release, Berry settled into married life and worked at an automobile assembly plant.

By early 1953, influenced by the guitar riffs and showmanship techniques of blues player, T-Bone Walker, he was performing in the evenings with the Johnnie Johnson Trio. His break came when he traveled to Chicago in May, 1955, and met Muddy Waters, who suggested he contact Leonard Chess of Chess Records.

With Chess, Berry recorded "Maybellene" — his adaptation of the country song "Ida Red" — which sold over a million copies, reaching #1 on Billboard's Rhythm and Blues chart.

By the end of the 1950s, Berry was an established star with several hit records and film appearances to his name as well as a lucrative touring career. He had also established his own St. Louis-based nightclub, called Berry's Club Bandstand.

But in January, 1962, Berry was sentenced to three years in prison for offenses under the Mann Act for transporting a 14-year-old girl across state lines.

After his release in 1963, Berry had several more hits, including "No Particular Place to Go," "You Never Can Tell" and "Nadine," but these did not achieve the same success, or lasting impact, of his 1950s songs.

By the 1970s, he was more in demand as a nostalgic live performer, playing his past hits with local backup bands of variable quality. His insistence on being paid in cash led to a jail sentence in 1979 — four months and community service for tax evasion.

Berry was among the first musicians to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on its opening in 1986, with the comment that he "laid the groundwork for not only a rock and roll sound but a rock and roll stance."

On March 18, 2017, police in St. Charles County, Missouri, were called to Berry's house, near Wentzville, Missouri, where he was found unresponsive. He was pronounced dead at the scene, aged 90, by his personal physician.

Berry's funeral was held on April 9, 2017, at The Pageant, in Berry's hometown of St. Louis, Missouri. He was remembered with a public viewing by family, friends and fans in The Pageant, a music club where he often performed, with his cherry-red guitar bolted to the inside lid of the coffin and with flower arrangements that included one sent by the Rolling Stones in the shape of a guitar.

One of Berry's attorneys estimated that his estate was worth $50 million, including $17 million in music rights. Berry's music publishing accounted for $13 million of the estate's value. The Berry estate owned roughly half of his songwriting credits (mostly from his later career), while BMG Rights Management controlled the other half; most of Berry's recordings are currently owned by Universal Music Group.In September, 2017, Dualtone, the label which released Berry's final album, Chuck, agreed to publish all his compositions in the United States.

Here, Berry performs “Johnny B. Goode.”

Anita O'Day, Newport Festival, 1958

Anita O'Day, iconic jazz singer, was born 104 years ago today.

Originally named Anita Belle Colton, O’Day was admired for her sense of rhythm and dynamics, and her early big band appearances shattered the traditional image of the "girl singer.” Refusing to pander to any female stereotype, O'Day presented herself as a "hip" jazz musician, wearing a band jacket and skirt as opposed to an evening gown.

She changed her surname from Colton to O'Day, pig Latin for "dough," slang for money. Along with Mel Tormé, O’Day is often grouped with the West Coast cool school of jazz.

Like Tormé, O'Day had some training in jazz drums (courtesy of her first husband, Don Carter). Her longest musical collaboration was with jazz drummer, John Poole. While maintaining a central core of hard swing, O'Day's skills in improvisation of rhythm and melody put her squarely among the pioneers of bebop.

She cited Martha Raye as the primary influence on her vocal style, also expressing admiration for Mildred Bailey, Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. O’Day always maintained that the accidental excision of her uvula during a childhood tonsillectomy left her incapable of vibrato, and unable to maintain long phrases.

That botched operation, she claimed, forced her to develop a more percussive style based on short notes and rhythmic drive.

However, when in good voice, she could stretch long notes with strong crescendos and a telescoping vibrato, e.g. her live version of "Sweet Georgia Brown" at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival, captured in Bert Stern's film, Jazz on a Summer's Day.

O’Day died November 23, 2006 at age 87.

Here, O’Day performs “Sweet Georgia Brown” and “Tea for Two” at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958.

This clip is from “Jazz on a Summer’s Day”

Anita O’Day: A Personal Remembrance

I believe it was about 2004. I was visiting Les Paul in his dressing room before his show at the Iridium Jazz Club in Manhattan. The jovial banter from Les was flying around the room — interrupted only when there was a knock on the door.

An older lady entered, Les rose from his seat and was extremely reverential to her. He was clearly delighted to see her and made an introduction to everyone: “This is Anita O’Day.”

I was blown away. I had heard her incredibly gifted jazz vocals in a show about 10 years earlier. I had experienced films of her magnificent voice at the 1958 Newport Festival. Now I was shaking her hand.

Les told me he had played with O’Day in hotel performances in the late 1930s, when she rose to become one of the top female vocalists in the nation. She was in the league with Billie Holiday, Dinah Shore, Helen O’Connell and Helen Forest.

They chatted, but it was clear that O’Day, then in her mid-80s, was having memory problems next to Les Paul’s razor sharp recall. To me, she seemed a bit out of it that night.

Soon, it was time for Les to go on stage. He asked me to escort O’Day to the bar and keep her occupied until he was ready for her. When he made the introduction, he wanted me to escort her through the audience to the stage. I told him I would be honored.

Ironically, I had already read O’Day’s 1981 memoir, “High Times, Hard Times,” about her amazing life and drug addictions. I knew her comeback story, but on this night I could not talk with her about it.

Her comprehension was very poor and unfortunately we didn’t have much of a conversation. I sat quietly with her at the bar and when Les introduced her, I did as instructed.

The appearance didn’t go well. Les would say things like, “it was New Years Eve, 1939, at the Hotel Pennsylvania, Anita, do you remember what we performed?”

Anita answered “no,” but Les always remembered. He played songs Anita was known for, but she could barely sing them. I felt very badly for her and blamed whoever had chided her to make that Iridium appearance on that night.

A year or two later, on Nov. 23, 2006, I read that Anita O’Day had died at age 87 in her sleep.

I wish I could say I had a more satisfying visit with this great jazz artist. But I can’t. Yet, I remember her amazing voice and wish I could have met her in 1958 when she was at the top of her game.

Les Paul and Frank Beacham

There can be no question that anyone would have been shaken by the events that transpired in the Memphis home of singer Al Green in the early morning hours of October 18, 1974 — 49 years ago today.

An ex-girlfriend burst in on him in the bath and poured a pot of scalding-hot grits on his back before retreating to a bedroom and shooting herself dead with Green's own gun.

Not everyone, however, would have processed the meaning of the incident quite the way that Green did. Believing that he had strayed from the righteous musical and spiritual course intended for him, Al Green had become a born-again Christian one year earlier.

But after the attack by Mary Woodson on this day in 1974, he began a process that would eventually lead him to renounce pop superstardom and all that it stood for.

Al Green, widely renowned as one of the greatest voices in soul music history, was at the absolute height of his powers in 1974. He had seven critically and commercially successful major-label albums behind him that included such timeless hits as "Tired Of Being Alone" (1971), "Let's Stay Together" (1971) and "I'm Still In Love With You" (1972).

He also, in the words of Davin Seay, who collaborated with Green on his 2000 autobiography, Take Me To The River, had a "basic animal appeal to women" that attracted many admirers, including Mary Woodson.

Woodson first made Green's acquaintance after leaving her husband and children behind in New Jersey and attending one of his concerts in upstate New York. On the night of the attack, she had shown up unexpectedly at Green's Memphis home after he returned from a concert appearance in San Francisco.

What exactly prompted her to act is unclear, but her actions not only left Al Green with severe burns that would require months of hospitalization, they also left him severely shaken emotionally and spiritually.

"He likes to distance the facts of his [religious] conversion from the terrible events of that night," said Seay, "but I think the Woodson incident kind of crystallized his need to move on, to sort of shut down one part of his life and open up another.''

By 1976, Al Green had become an ordained Baptist minister and purchased a Memphis church where he still preaches today. He also renounced secular R&B for a time, recording gospel music almost exclusively through the late 1970s and early 1980s before embracing his past and reviving his earlier repertoire again in the late 1980s.

Here, Green performs on David Letterman’s show.

A.J. Liebling looks at a book while at the counter of an unidentified bookstore in New York City on October 24, 1961

Photo by Fred W. McDarrah

A.J. Liebling, noted writer for The New Yorker, was born 119 years ago today.

Born into a well-off family on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, Liebling’s father was a Jewish immigrant from Austria who worked in New York's fur industry. His mother came from a Jewish family in San Francisco.

After early schooling in New York, Liebling was admitted to Dartmouth College in the fall of 1920. His primary activity during his undergraduate career was as a contributor to the Jack-O-Lantern, Dartmouth's nationally known humor magazine.

He left Dartmouth without graduating, later claiming he was "thrown out for missing compulsory chapel attendance." He then enrolled in the School of Journalism at Columbia University.

After finishing at Columbia, he began his career as a journalist at the Evening Bulletin of Providence, Rhode Island. He worked briefly in the sports department of The New York Times, from which he supposedly was fired for listing the name "Ignoto" (Italian for "unknown") as the referee in results of games.

In the summer 1926, Liebling sailed to Europe where he studied French medieval literature at the Sorbonne in Paris. By his own admission his devotion to his studies was purely nominal, as he saw the year as a chance to absorb French life and appreciate French food.

Although he stayed for little more than a year, this interval inspired a lifelong love for France and the French, later renewed in his war reporting. He returned to Providence in autumn 1927 to write for the Journal.

He then moved to New York, where he proceeded to campaign for a job on Joseph Pulitzer's New York World, which carried the work of James M. Cain and Walter Lippmann and was known at the time as "the writer's paper."

In order to attract the attention of the city editor, James W. Barrett, Liebling hired an out-of-work Norwegian seaman to walk for three days outside the Pulitzer Building, on Park Row, wearing sandwich boards that read Hire Joe Liebling.

It turned out that Barrett habitually used a different entrance on another street, and never saw the sign. He wrote for the World (1930–31) and the World-Telegram (1931–35).

Liebling joined The New Yorker in 1935. His best pieces from the late thirties are collected in Back Where I Came From (1938) and The Telephone Booth Indian (1942).

During World War II, Liebling was active as a war correspondent, filing many stories from Africa, England and France. His war began when he flew to Europe in October, 1939 to cover its early battles, lived in Paris until June 10, 1940, and then returned to the United States until July, 1941, when he flew to Britain.

He sailed to Algeria in November, 1942 to cover the fighting on the Tunisian front (January to May 1943). His articles from these days are collected in The Road Back to Paris (1944).

He participated in the Normandy landings on D Day, and he wrote a memorable piece concerning his experiences under fire aboard a U.S. Coast Guard-staffed landing craft off Omaha Beach.

He afterwards spent two months in Normandy and Brittany, and was with the Allied forces when they entered Paris. He wrote afterwards: "For the first time in my life and probably the last, I have lived for a week in a great city where everybody was happy." Liebling was awarded the Cross of the Légion d'honneur by the French government for his war reporting.

Following the war he returned to regular magazine fare and for many years after he wrote a New Yorker monthly feature called "Wayward Press," in which he analyzed the U.S. press. Liebling was also an avid fan of boxing, horse racing and food, and frequently wrote about these subjects.

In 1961, Liebling published The Earl of Louisiana, originally published as a series of articles in The New Yorker in which he covered the trials and tribulations of the governor of Louisiana, Earl K. Long, the younger brother of the Louisiana politician Huey Long.

On December 19, 1963, Liebling was hospitalized for bronchopneumonia. He died on December 28 at Mount Sinai Hospital, and was buried in the Green River Cemetery, East Hampton, New York.

Wynton Marsalis is 62 years old today.

Marsalis is a trumpeter, composer, teacher, music educator and Artistic Director of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City. He has promoted the appreciation of classical and jazz music often to young audiences. A jazz recording of his was the first of its kind to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music.

Marsalis is the son of jazz musician Ellis Marsalis, Jr. (pianist), grandson of Ellis Marsalis, Sr. and brother of Branford (saxophonist), Delfeayo (trombonist) and Jason (drummer).

Born in New Orleans, Marsalis is the second of six sons of Dolores and Ellis Louis Marsalis, Jr., a pianist and music professor. At an early age, he exhibited an aptitude for music. At age eight, he performed traditional New Orleans music in the Fairview Baptist Church band led by banjoist, Danny Barker, and at 14, he performed with the New Orleans Philharmonic.

During high school, Marsalis performed with the New Orleans Symphony Brass Quintet, New Orleans Community Concert Band, New Orleans Youth Orchestra, New Orleans Symphony, various jazz bands and with a local funk band, the Creators.

He was the youngest musician admitted to Tanglewood's Berkshire Music Center, where he won the school's Harvey Shapiro Award for outstanding brass student. He then moved to New York City to attend Juilliard in 1979, and picked up gigs around town.

During this period, Marsalis received a grant from the National Endowment of the Arts to spend time and study with trumpet innovator, Woody Shaw, one of Marsalis' major influences at the time.

In 1980, he joined the Jazz Messengers led by Art Blakey. In the years that followed, Marsalis performed with Sarah Vaughan, Dizzy Gillespie, Sweets Edison, Clark Terry, Sonny Rollins, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams and countless other jazz musicians.

In 1995, PBS premiered Marsalis on Music, an educational television series on jazz and classical music hosted and written by Marsalis. Also, in 1995, National Public Radio aired the first of Marsalis' 26-week series, entitled Making the Music. His radio and television series were awarded the George Foster Peabody Award.

Marsalis has also written five books: Sweet Swing Blues on the Road, Jazz in the Bittersweet Blues of Life, To a Young Musician: Letters from the Road, Jazz ABZ (an A to Z collection of poems celebrating jazz greats) and his most recent release Moving to Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life.

Here, Marsalis performs “Cherokee.”

On October 18, 1933 — 90 years ago — philosopher-inventor, R. Buckminster Fuller, applied for a patent for his Dymaxion Car.

The Dymaxion — the word itself was another Fuller invention, a combination of "dynamic," "maximum" and "ion" — looked and drove like no vehicle anyone had ever seen.

It was a three-wheeled, 20-foot-long, pod-shaped automobile that could carry 11 passengers and travel as fast as 120 miles per hour. It got 30 miles to the gallon, could U-turn in a distance equal to its length and could parallel park just by pivoting its wheels toward the curb and zipping sideways into its parking space.

It was stylish, efficient and eccentric and it attracted a great deal of attention. Celebrities wanted to ride in it and rich men wanted to invest in it. But in the same month that Fuller applied for his patent, one of his prototype Dymaxions crashed, killing the driver and alarming investors so much that they withdrew their money from the project.

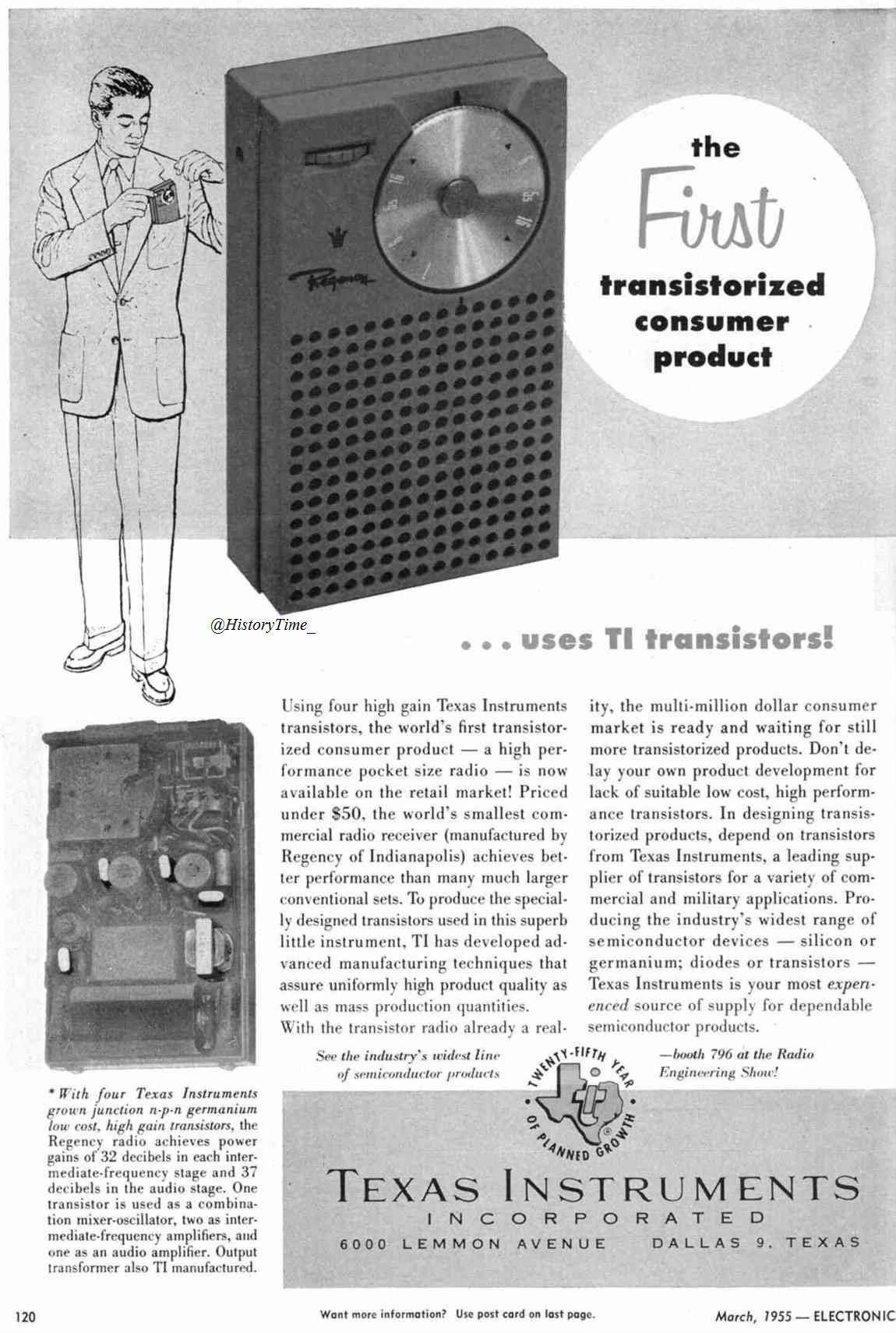

On October 18, 1954 — 69 years ago — Regency introduced the TR-1, the first transistor radio. The device introduced the “under the pillow” club, that allowed white people to listen secretly to black music. I had one and wish I still had it.