Bill Wyman, former English bass guitarist for the Rolling Stones, is 87 years old today

Bill Wyman is 87 years old today.

Wyman is an English musician who was the bass guitarist for the Rolling Stones from 1962 until 1993.

Since 1997, he has recorded and toured with his own band, Bill Wyman's Rhythm Kings. He has worked producing both records and film, and has scored music for film in movies and television.

Wyman has kept a journal since he was a child after World War II. It has been useful to him as an author who has written seven books, selling two million copies.

His love of art has additionally led to his proficiency in photography and his photographs have hung in galleries around the world.

Wyman's lack of funds in his early years led him to create and build his own fretless bass guitar. He became an amateur archaeologist and enjoys relic hunting.

He designed and markets a patented Bill Wyman signature metal detector, which he has used to find relics in the English countryside dating back to the era of the Roman Empire.

As a businessman, he owns several establishments including the famous Sticky Fingers Café, a rock & roll-themed bistro serving American cuisine first opened in 1989 in the Kensington area of London and later, two additional locations in Cambridge and Manchester, England.

In March, 2016, Wyman said he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and had made a full recovery.

Here, Bill Wyman is interviewed in 2005.

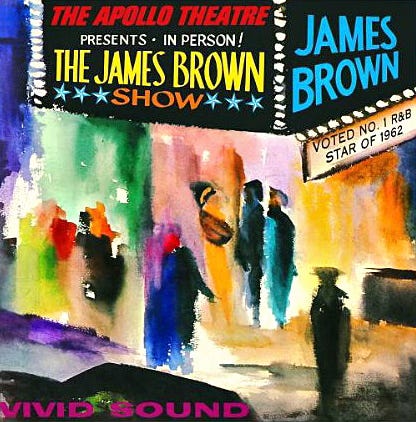

On this day in 1962 — 61 years ago — James Brown recorded his breakthrough album, Live at the Apollo.

Brown began his professional career at a time when rock and roll was opening new opportunities for black artists to connect with white audiences. But the path he took to fame did not pass through Top 40 radio or through The Ed Sullivan Show and American Bandstand.

Brown would make his appearance in all of those places eventually, but only after a decade spent performing almost exclusively before black audiences and earning his reputation as the “Hardest Working Man in Show Business.”

On this day in 1962, he took a major step toward his eventual crossover and conquest of the mainstream with an electrifying performance on black America's most famous stage — a performance recorded and later released as Live at the Apollo (1963), the first breakthrough album of James Brown's career.

By the time 1962 rolled around, Brown was one of the most popular figures on the R&B scene, not so much on the strength of his recordings, but on the strength of his live act.

As he would throughout his long career, Brown ran his band, the Famous Flames, like a military unit, demanding of his instrumentalists and backing vocalists the same perfection he demanded of himself.

Even in the middle of a performance, Brown would turn around and dish out fines for missed or flubbed notes, all without missing or flubbing a dance step himself.

At the midnight show at the Apollo on October 24, 1962, however, every member of Brown's band knew that the fines they faced would be far greater than normal. "You made a mistake that night," band member Bobby Byrd told Rolling Stone magazine, "the fine would move from five or ten dollars to fifty or a hundred dollars."

The reason was simple. Having failed to convince the head of his label, King Records, to record and release the performance as a live album, James Brown, a man who was famously wise to the value of a dollar, was financing the Apollo recording himself.

In the end, the show went off not only without a hitch, but with such success that the famously tough Apollo crowd was in a state of rapture.

Released in May, 1963, Live at the Apollo ended up spending an astonishing 66 weeks on the Billboard album chart and selling upwards of a million copies, giving James Brown his first smash hit album and setting him on a course for his incredible crossover success in the mid-1960s and beyond.

Thanks History.com

On this day in 1963 — 60 years ago — Bob Dylan recorded “The Times They Are A-Changin” at Columbia Recording Studios in New York City.

Dylan wrote the song as a deliberate attempt to create an anthem of change for the time, influenced by Irish and Scottish ballads. It was released on March 8, 1965 on the album by the same name.

Since its release, the song has been influential to views on society, with critics noting the universal lyrics as contributing to the song's lasting message of change.

Dylan has occasionally performed it in concert. The song has been covered by many different artists, including Nina Simone; Josephine Baker; the Byrds; the Seekers; Peter, Paul and Mary; Tracy Chapman; Simon & Garfunkel; Runrig; the Beach Boys; Joan Baez; Phil Collins; Billy Joel; Bruce Springsteen; Me First and the Gimme Gimmes; Brandi Carlile; and Burl Ives.

Dylan recalled writing the song as a deliberate attempt to create an anthem of change for the moment. In 1985, he told Cameron Crowe, "This was definitely a song with a purpose. It was influenced of course by the Irish and Scottish ballads ...'Come All Ye Bold Highway Men', 'Come All Ye Tender Hearted Maidens'.

“I wanted to write a big song, with short concise verses that piled up on each other in a hypnotic way. The civil rights movement and the folk music movement were pretty close for a while and allied together at that time."

May Pang with Frank Beacham, October 23, 2013, New York City

May Pang is 73 years old today.

Pang is a Chinese-American, best known as the former girlfriend of John Lennon. She had previously worked as a personal assistant and production coordinator for Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono.

In 1973, when Lennon and Ono separated, Pang and Lennon had a relationship lasting over 18 months — during a time which Lennon later referred to as his "Lost Weekend."

Pang subsequently produced two books about their relationship: a memoir, Loving John (Warner, 1983), and a book of photographs, Instamatic Karma (St. Martin's Press, 2008).

Pang was married to producer Tony Visconti from 1989 to 2000 and had two children, Sebastian and Lara.

Jiles Perry "J. P." Richardson, Jr., commonly known as The Big Bopper, was born 93 years ago today.

A disc jockey, singer and songwriter whose big voice and exuberant personality made him an early rock and roll star, Richardson is best known for his recording of "Chantilly Lace.”

On February 3, 1959, a day that has become known as The Day the Music Died (from Don McLean's song, "American Pie"), Richardson was killed in a plane crash in Iowa, along with Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the pilot, Roger Peterson.

J. P. Richardson was born in Sabine Pass, Texas, the oldest son of oil-field worker, Jiles Perry Richardson, Sr. and his wife Elise. He graduated from Beaumont High School in 1947 and played on the "Royal Purple" football team as a defensive lineman, wearing #85. He later studied pre-law at Lamar College, and was a member of the band and chorus.

Richardson worked part-time at Beaumont, Texas radio station, KTRM (now KZZB). He was hired by the station full-time in 1949 and quit college.

Richardson married Adrianne Joy Fryou on April 18, 1952. Their daughter, Debra Joy, was born in December, 1953. Soon after, he was promoted to supervisor of announcers at KTRM.

Richardson had seen the college students doing a dance called The Bop, and he decided to call himself, "The Big Bopper." His new radio show ran from 3:00 pm to 6:00 pm. Richardson soon became the station's program director.

Richardson is credited for creating the first music video in 1958, and recorded an early example himself.

Richardson, who played guitar, began his musical career as a songwriter. George Jones later recorded Richardson's "White Lightning," which became Jones' first #1 country hit in 1959 (#73 on the pop charts).

Richardson also wrote "Running Bear" for Johnny Preston, his friend from Port Arthur, Texas. The inspiration for the song came from Richardson's childhood memory of the Sabine River, where he heard stories about Indian tribes.

Richardson sang background on "Running Bear," but the recording wasn't released until September, 1959, after his death. Within several months it became #1.

The man who launched Richardson as a recording artist was Harold "Pappy" Daily from Houston. Daily was promotion director for Mercury and Starday Records and signed Richardson to Mercury.

Richardson's first single, "Beggar To A King," had a country flavor, but failed to gain any chart action. He soon cut "Chantilly Lace" as "The Big Bopper" for Pappy Daily's D label.

Mercury bought the recording and released it in the summer of 1958. It reached #6 on the pop charts and spent 22 weeks in the national Top 40. It also inspired an answer record by Jayne Mansfield, "That Makes It."

In "Chantilly Lace," Richardson pretends to have a flirting phone conversation with his girlfriend. The Mansfield record suggests what his girlfriend might have been saying at the other end of the line.

With the success of "Chantilly Lace," Richardson took time off from KTRM radio and joined Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and Dion and the Belmonts for a "Winter Dance Party" tour. On the eleventh night of the tour, Holly chartered an airplane to fly them to the next show in Moorhead, Minnesota.

The musicians had been traveling by bus for over a week, and it had already broken down once. They were tired, they had not been paid yet and all of their clothes were dirty. With the airplane, Holly could arrive early, do everyone's laundry and get some rest.

Roger Peterson, the 21-year old pilot, had agreed to take the singers to Fargo, North Dakota, where the airport serves the cities of Moorhead and Fargo. A snowstorm was inbound, and the pilot was fatigued from a 17-hour workday, but agreed to fly the trip.

The musicians packed up their instruments and finalized the flight arrangements. Buddy Holly's bass player, Waylon Jennings, was scheduled to fly on the plane, but gave his seat up to the Big Bopper, who was suffering from influenza.

Holly's guitarist, Tommy Allsup, agreed to flip a coin with Ritchie Valens for the remaining seat. Valens won. The three musicians boarded the red and white single-engine Beechcraft Bonanza at the Mason City Airport around 12:30 AM on February 3. Snow blew across the runway, but the sky was clear.

Peterson received clearance from the control tower, taxied down the runway and took off. He was never told of two weather advisories that warned of an oncoming blizzard ahead.

The plane remained airborne only a few minutes. No one is sure what went wrong. The best guess is Peterson flew directly into the blizzard, lost visual reference and accidentally flew down instead of up. The four-passenger plane plowed into a cornfield at over 220 mph, flipping over on itself and tossing the passengers into the air.

The bodies of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper were jettisoned from the plane, landed yards from the wreckage and lay there for ten hours as snowdrifts formed around them. Roger Peterson's body was not jettisoned from the plane. Because of the weather, no one reached the crash site until later in the morning.

Here’s “The Big Bopper” performing “Chantilly Lace” in 1958.

Moss Hart with Arlene Francis on the game show, Answer Yes or No, in 1950

Moss Hart, playwright and theatre director, was born 119 years ago today.

Hart was born in New York City and grew up in relative poverty with his English-born Jewish immigrant parents in The Bronx and in Sea Gate, Brooklyn.

Early on he had a strong relationship with his Aunt Kate, with whom he later lost contact due to a falling out between her and his parents, and Kate's weakening mental state. She piqued his interest in the theater and took him to see performances often. Hart even went so far as to create an "alternate ending" to her life in his book, Act One.

He writes that she died while he was working on out-of-town tryouts for The Beloved Bandit. Later, Kate became eccentric and then disturbed, vandalizing Hart's home, writing threatening letters and setting fires backstage during rehearsals for Jubilee.

But his relationship with her was formative. He learned that the theater made possible "the art of being somebody else… not a scrawny boy with bad teeth, a funny name… and a mother who was a distant drudge."

After working several years as a director of amateur theatrical groups and an entertainment director at summer resorts, he scored his first Broadway hit with Once in a Lifetime (1930), a farce about the arrival of the sound era in Hollywood. The play was written in collaboration with Broadway veteran George S. Kaufman, who regularly wrote with others, notably Marc Connelly and Edna Ferber.

During the next decade, Kaufman and Hart teamed on a string of successes, including You Can't Take It With You (1936) and The Man Who Came to Dinner (1939). Though Kaufman had hits with others, Hart is generally conceded to be his most important collaborator.

Sonny Terry was born 111 years ago today.

Terry was a blind American Piedmont blues musician. He was widely known for his energetic blues harmonica style, which frequently included vocal whoops and hollers, and imitations of trains and fox hunts.

Terry was born in Greensboro, North Carolina. His father, a farmer, taught him to play basic blues harp as a youth. He sustained injuries to his eyes and lost his sight by the time he was 16, which prevented him from doing farm work himself.

In order to earn a living, Terry was forced to play music. He began playing in Shelby, North Carolina. After his father died, he began playing in the trio of Piedmont blues-style guitarist Blind Boy Fuller.

When Fuller died in 1941, he established a long-standing musical relationship with Brownie McGhee, and the pair recorded numerous songs together. The duo became well-known among white audiences, as they joined the growing folk movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Here, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee perform “Hooray, Hooray, These Women Is Killin’ Me” in 1966.

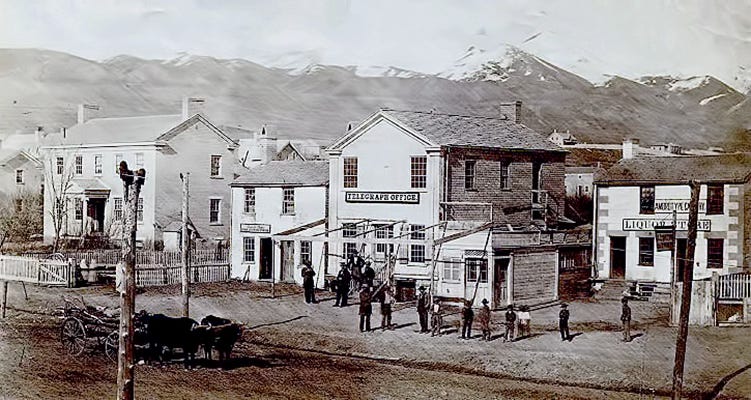

The Telegraph Office shows where the east and west coasts lines were joined in 1861.

On this day in 1861 — 162 years ago — workers of the Western Union Telegraph Company linked the eastern and western telegraph networks of the nation at Salt Lake City, Utah, completing a transcontinental line that for the first time allowed instantaneous communication between Washington, D.C. and San Francisco.

Stephen J. Field, chief justice of California, sent the first transcontinental telegram to President Abraham Lincoln, predicting that the new communication link would help ensure the loyalty of the western states to the Union during the Civil War.

The push to create a transcontinental telegraph line had begun only a little more than year before when Congress authorized a subsidy of $40,000 a year to any company building a telegraph line that would join the eastern and western networks.

The Western Union Telegraph Company, as its name suggests, took up the challenge, and the company immediately began work on the critical link that would span the territory between the western edge of Missouri and Salt Lake City.

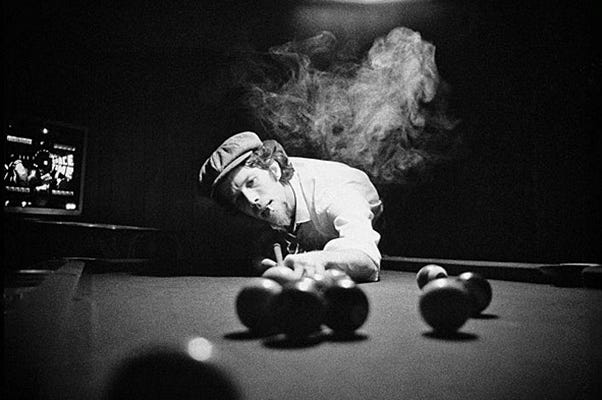

Tom Waits, circa mid-1970s

Photo by Scott Smith