Big Bill Broonzy, prolific blues performer, was born 120 years ago today

Bill Broonzy on the movie set of Low Light and Blue Smoke, Brussels, December, 1955

Big Bill Broonzy was born 120 years ago today.

A prolific blues singer, songwriter and guitarist, Broonzy’s career began in the 1920s when he played country blues to mostly African-American audiences. Through the ‘30s and ‘40s, he successfully navigated a transition in style to a more urban blues sound popular with working class African-American audiences.

In the 1950s, a return to his traditional folk-blues roots made him one of the leading figures of the emerging American folk music revival and an international star. His long and varied career marks him as one of the key figures in the development of blues music in the 20th century.

Broonzy copyrighted more than 300 songs during his lifetime, including both adaptations of traditional folk songs and original blues songs. As a blues composer, he was unique in that his compositions reflected the many vantage points of his rural-to-urban experiences.

Born Lee Conley Bradley, "Big Bill" was one of Frank Broonzy (Bradley) and Mittie Belcher's 17 children. His birth site and date are disputed. While he claimed birth in Scott County, Mississippi, an entire body of emerging research compiled by the blues historian, Robert Reisman, suggests that Broonzy was actually born in Jefferson County, Arkansas.

Broonzy claimed he was born in 1893 and most sources report that year, but after his death, family records suggested that the year was actually 1903. Soon after his birth the family moved to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where Bill spent his youth. He began playing music at an early age.

At the age of 10, he made himself a fiddle from a cigar box and learned how to play spirituals and folk songs from his uncle, Jerry Belcher. He and a friend, Louis Carter, who played a homemade guitar, began performing at social and church functions.

These early performances included playing at "two stages"— picnics where whites danced on one side of the stage and blacks on the other.

On the proposition that he was born in 1898 rather than earlier or later, sources suggest that in 1915, 17-year-old Broonzy was married and working as a sharecropper. He had decided to give up the fiddle and become a preacher. There is a story that he was offered $50 and a new violin if he would play four days at a local venue. Before he could respond to the offer, his wife took the money and spent it, so he had to play.

In 1916, his crop and stock were wiped out by drought. Broonzy went to work locally until he was drafted into the Army in 1917. He served two years in Europe during World War I.

After his discharge from the Army in 1919, Broonzy returned to Pine Bluff, Arkansas where he was called a racial epithet and told by a white man he knew before the war that he needed to "hurry up and get his soldier uniform off and put on some overalls." He immediately left Pine Bluff and moved to the Little Rock area, but in 1920 moved north to Chicago in search of opportunity.

After arriving in Chicago, Broonzy made the switch to guitar. He learned guitar from minstrel and medicine show veteran, Papa Charlie Jackson, who began recording for Paramount Records in 1924. Through the 1920s Broonzy worked a string of odd jobs, including Pullman porter, cook, foundry worker and custodian to supplement his income. But his main interest was always music.

He played regularly at rent parties and social gatherings, steadily improving his guitar playing. During this time he wrote one of his signature tunes, a solo guitar piece called "Saturday Night Rub.” Thanks to his association with Jackson, Broonzy was able to get an audition with Paramount executive, J. Mayo Williams.

His initial test recordings, made with his friend, John Thomas, on vocals, were rejected, but Broonzy persisted. His second try, a few months later, was more successful. His first record, "Big Bill's Blues" backed with "House Rent Stomp," credited to "Big Bill and Thomps" (Paramount 12656), was released in 1927.

Although the recording was not well-received, Paramount retained their new talent and the next few years saw more releases by "Big Bill and Thomps." The records continued to sell poorly. Reviewers considered his style immature and derivative.

In 1930, Paramount for the first time used Broonzy's full name on a recording, "Station Blues" – albeit misspelled as "Big Bill Broomsley." Record sales continued to be poor. Broonzy supported himself working at a grocery store.

Broonzy was picked up by Lester Melrose, who produced acts for various labels including Champion and Gennett Records. He recorded several sides which were released in the spring of 1931 under the name "Big Bill Johnson.”

In March, 1932, he traveled to New York City and began recording for the American Record Corporation on their line of less expensive labels: (Melotone, Perfect Records, et al.). These recordings sold better and Broonzy was becoming better known. Back in Chicago he was working regularly in South Side clubs, and even toured with Memphis Minnie.

In 1934, Broonzy moved to Bluebird Records and began recording with pianist Bob "Black Bob" Call. His fortunes soon improved. With Call his music was evolving to a stronger R&B sound, and his singing sounded more assured and personal.

In 1937, Broonzy began playing with the pianist, Joshua Altheimer. He recorded and performed using a small instrumental group, including "traps" (drums) and double bass as well as one or more melody instruments (horns and/or harmonica).

In March, 1938, Broonzy began recording for Vocalion Records. His reputation grew and in 1938 he was asked to fill in for the recently deceased Robert Johnson at the John H. Hammond-produced From Spirituals to Swing concert at Carnegie Hall. He also appeared in the 1939 concert at the same venue.

His success led him in this same year to a small role in Swingin' the Dream, Gilbert Seldes's jazz adaptation of Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream, set in 1890 New Orleans. The show featured Louis Armstrong as Bottom and Maxine Sullivan as Titania alone with the Benny Goodman sextet.

Broonzy expanded his work during this period as he honed his song writing skills which showed a knack for appealing to his more sophisticated city audience as well as people that shared his country roots. His work in this period shows he performed across a wider musical spectrum than almost any other bluesman before or since including ragtime, hokum blues, country blues, city blues, jazz tinged songs, folk songs and spirituals.

After World War II, Broonzy recorded songs that were the bridge that allowed many younger musicians to cross over to the future of the blues: the electric blues of post war Chicago. His 1945 recordings of "Where the Blues Began" with Big Maceo on piano and Buster Bennett on sax, or "Martha Blues" with Memphis Slim on piano, clearly show the way forward. One of his best-known songs, "Key to the Highway," appeared at this time.

At the start of the 1950s, Broonzy became part of a touring folk music revue formed by Win Stracke called I Come for to Sing, which also included Studs Terkel and Lawrence Lane. Terkel called him the key figure in this group. The group had some success thanks to the emerging folk revival movement. The exposure made it possible for Broonzy to tour Europe in 1951.

In Europe, Broonzy was greeted with standing ovations and critical praise wherever he played. The tour marked a turning point in his fortunes, and when he returned to the United States he was a featured act with many prominent folk artists such as Pete Seeger, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

From 1953 on, Broonzy’s financial position became more secure and he was able to live well on his music earnings. He returned to his solo folk-blues roots, and traveled and recorded extensively.

Broonzy's numerous performances during the 1950s in the UK, and in particular at folk clubs in London and Edinburgh, were influential in the nascent British folk revival. Many British musicians on the folk scene, such as Bert Jansch, cited Broonzy as an important influence.

Broonzy's own influences included the folk music, spirituals, work songs, ragtime music, hokum and country blues he heard growing up, and the styles of his contemporaries, including Jimmie Rodgers, Blind Blake, Son House and Blind Lemon Jefferson.

Broonzy combined all these influences into his own style of the blues that foreshadowed the post-war Chicago blues sound, later refined and popularized by artists such as Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon. In 1980, he was inducted into the first class of the Blues Hall of Fame along with 20 other of the world's greatest blues legends.

Broonzy as an acoustic guitar player, inspired Muddy Waters, Memphis Slim, Ray Davies, John Renbourn, Rory Gallagher, Ben Taylor and Steve Howe. Ronnie Wood of The Rolling Stones claims that Broonzy's track, "Guitar Shuffle," is his favorite guitar music. "It was one of the first tracks I learnt to play, but even to this day I can't play it exactly right," said Wood.

Eric Clapton has cited Bill Broonzy as a major inspiration: Broonzy "became like a role model for me, in terms of how to play the acoustic guitar."

Broonzy died in 1958 at age 65 in Chicago.

Here, Broonzey performs “Hey Hey”

The basement studio in 2011 at Big Pink where Bob Dylan and the Band recorded many of The Basement Tapes 56 years ago.

The room is still being used as a studio

Photo by Frank Beacham

Bob Dylan and the Band began recording The Basement Tapes 56 years ago and officially released The Basement Tapes album 48 years ago today.

The album was Dylan's sixteenth studio album. The songs featuring Dylan's vocals were recorded in 1967 — eight years before the album's release, at houses in and around Woodstock, New York, where Dylan and the Band lived.

Although most of the Dylan songs had appeared on bootleg records, The Basement Tapes marked their first official release.

During his world tour of 1965–66, Dylan was backed by a five-member rock group, the Hawks, who would subsequently become the Band. After Dylan was injured in a motorcycle accident in July, 1966, four members of the Hawks gravitated to the vicinity of Dylan's home in the Woodstock area to collaborate with him on music and film projects.

While Dylan was concealed from public view during an extended period of convalescence in 1967, they recorded more than 100 tracks together, comprising original compositions, contemporary covers and traditional material.

Dylan's new style of writing moved away from the urban sensibility and extended narratives that had characterized his most recent albums — Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde — toward songs that were more intimate and which drew on many styles of traditional American music.

While some of the basement songs are humorous, others dwell on nothingness, betrayal and a quest for salvation. In general, they possess a rootsy quality anticipating the Americana genre. For some critics, the songs on The Basement Tapes, which circulated widely in unofficial form, mounted a major stylistic challenge to rock music in the late sixties.

When Columbia Records prepared the album for official release in 1975, eight songs recorded solely by the Band — in various locations between 1967 and 1975 — were added to sixteen songs recorded by Dylan and the Band in 1967.

Overdubs were added in 1975 to songs from both categories. The Basement Tapes was critically acclaimed upon release, and reached #7 on the Billboard 200 album chart.

Rick Danko recalled that he, Richard Manuel and Garth Hudson joined Robbie Robertson in West Saugerties, a few miles from Woodstock, in February, 1967. The three of them moved into a house on Stoll Road nicknamed “Big Pink.”

Robertson lived nearby with his future wife, Dominique. Danko and Manuel had been invited to Woodstock to collaborate with Dylan on a film he was editing — Eat the Document — a rarely seen account of Dylan's 1966 world tour.

At some point between March and June, 1967, Dylan and the four Hawks began a series of informal recording sessions, initially at the so-called Red Room of Dylan's house, Hi Lo Ha, in the Byrdcliffe area of Woodstock.

In June, the recording sessions moved to the basement of Big Pink. Hudson set up a recording unit, using two stereo mixers and a tape recorder borrowed from Grossman, as well as a set of microphones on loan from folk trio, Peter, Paul and Mary.

Dylan would later tell Jann Wenner, "That's really the way to do a recording — in a peaceful, relaxed setting — in somebody's basement. With the windows open ... and a dog lying on the floor." For the first couple of months, they were merely "killing time," according to Robertson, with many early sessions devoted to covers.

"With the covers Bob was educating us a little," recalls Robertson. "The whole folkie thing was still very questionable to us — it wasn't the train we came in on. He'd come up with something like 'Royal Canal,' and you'd say, 'This is so beautiful! The expression!' ... He remembered too much, remembered too many songs too well.

“He'd come over to Big Pink, or wherever we were, and pull out some old song — and he'd prepped for this. He'd practiced this, and then come out here, to show us."

Songs recorded at the early sessions included material written or made popular by Johnny Cash, Ian & Sylvia, John Lee Hooker, Hank Williams and Eric Von Schmidt, as well as traditional songs and standards. Linking all the recordings, both new material and old, is the way in which Dylan re-engaged with traditional American music.

Biographer Barney Hoskyns observed that both the seclusion of Woodstock and the discipline and sense of tradition in the Hawks' musicianship were just what Dylan needed after the "globe-trotting psychosis" of the 1965–66 tour. Dylan began to write and record new material at the sessions.

According to Hudson, "We were doing seven, eight, ten, sometimes fifteen songs a day. Some were old ballads and traditional songs ... but others Bob would make up as he went along. ... We'd play the melody, he'd sing a few words he'd written, and then make up some more, or else just mouth sounds or even syllables as he went along. It's a pretty good way to write songs."

Dylan recorded around thirty new compositions with the Hawks, including some of the most celebrated songs of his career: "I Shall Be Released," "This Wheel's on Fire," "Quinn the Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn)," "Tears of Rage" and "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere."

Two of these featured his lyrics set to music by members of the Band. Danko wrote the music of "This Wheel's on Fire.”

Manuel, who composed "Tears of Rage," described how Dylan "came down to the basement with a piece of typewritten paper ... and he just said, 'Have you got any music for this?' ... I had a couple of musical movements that fit ... so I just elaborated a bit, because I wasn't sure what the lyrics meant. I couldn't run upstairs and say, 'What's this mean, Bob: "Now the heart is filled with gold as if it was a purse"?'"

As tapes of Dylan's recordings circulated in the music industry, journalists became aware of their existence. In June, 1968, Jann Wenner wrote a front-page Rolling Stone story headlined, "Dylan's Basement Tape Should Be Released."

Wenner listened to the fourteen-song demo and reported, "There is enough material — most all of it very good — to make an entirely new Bob Dylan album, a record with a distinct style of its own." He concluded, "Even though Dylan used one of the finest rock and roll bands ever assembled on the Highway 61 album, here he works with his own band for the first time. Dylan brings that instinctual feel for rock and roll to his voice for the first time. If this were ever to be released it would be a classic."

Reporting such as this whetted the appetites of Dylan fans. In July, 1969, the first rock bootleg appeared in California, entitled Great White Wonder. The double album consisted of seven songs from the Woodstock basement sessions, plus some early recordings Dylan had made in Minneapolis in December, 1961 and one track recorded from The Johnny Cash Show.

In January, 1975, Dylan unexpectedly gave permission for the release of a selection of the basement recordings. Engineer Rob Fraboni was brought to clean up the recordings still in the possession of Garth Hudson, the original engineer.

The cover photograph for the 1975 album was taken by designer and photographer Reid Miles in the basement of a Los Angeles YMCA. It poses Dylan and the Band alongside characters suggested by the songs: a woman in a Mrs. Henry T-shirt, an Eskimo, a circus strongman and a dwarf who has been identified as Angelo Rossitto.

Robertson wears a blue Mao-style suit and Manuel wears an RAF flight lieutenant uniform.

"Listening to The Basement Tapes now, it seems to be the beginning of what is called Americana or alt.country," wrote Billy Bragg. "The thing about alt.country which makes it 'alt' is that it is not polished. It is not rehearsed or slick. Neither are The Basement Tapes. Remember that The Basement Tapes holds a certain cultural weight which is timeless — and the best Americana does that as well."

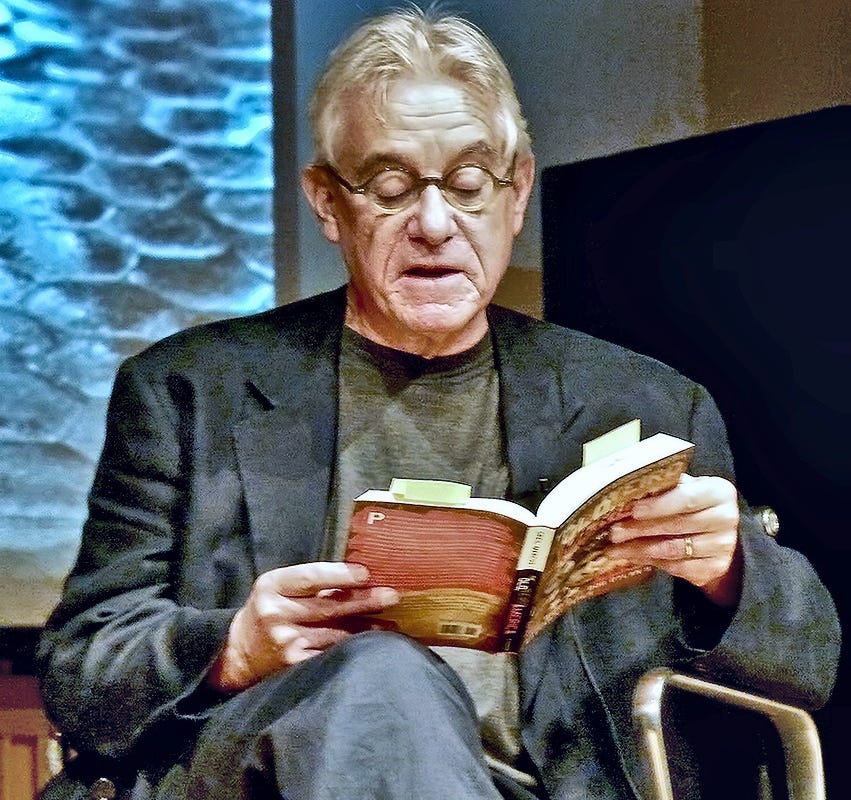

Greil Marcus reads from “The Old, Weird America”

Photo by Frank Beacham

In the 1960s, figures from an older world reappeared like ghosts.

Between June and October of 1967 — 56 years ago — they met almost daily in the basement of a house in West Saugerties, New York. The house was called Big Pink.

The group recorded more than a 100 performances of commonplace or original songs. Fourteen of the songs were pressed as an acetate and sent to other musicians. The basement tapes became a public secret — then a legend.

When the first Basement Tapes was officially released on this day in 1975 — 48 years ago — it climbed to the Top 10. Dylan expressed surprise: “I thought everybody already had them.”

Greil Marcus, in his book, The Old, Weird America, wrote the recordings were “a laboratory where, for a few months, certain bedrock strains of American cultural language were retrieved and reinvented.’’ The basement sessions, Marcus wrote, are buried outside the margins of the history books, in characters like Dock Boggs.

He believes there was “a fatal confusion’’ of art and life promulgated during the folk revival, when, as he puts it, “The kind of life that equaled art was defined by suffering, deprivation, poverty and social exclusion.’’

To the purist who prizes “authenticity’’ over individual vision, wrote Marcus, “the poor are art because they sing their lives without mediation and without reflection.” For a musician to create songs that could stand alongside the folk legacy — which Dylan called “nothing but mystery’’ — there must be conscious artifice, Marcus wrote.

After Dylan’s “unmasking’’ by hostile audiences, Marcus argued, the basement sessions were Dylan’s reassertion that “sometimes it is only the mask of distance, of vanishing, that lets you speak, that gives you the freedom to say what you mean without immediately having to stake your life on every word.’’

In Marcus’ view, the occult lineage of “the old, weird America” is a passing down of that ability to “begin the story again from the beginning” and raise a living present from the dead artifacts of the past.

What Marcus heard in the “sepias and washed-out Technicolor’’ of the basement tapes is a song of that resurrection.

Peter Lorre was born 119 years ago today.

An Austrian-born American actor of Jewish descent, Lorre caused an international sensation with his portrayal of a serial killer who preys on little girls in the 1931 German film, M, directed by Fritz Lang.

When the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, Lorre took refuge first in Paris and then London, where he was noticed by Ivor Montagu, associate producer for The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), who reminded the film's director, Alfred Hitchcock, about Lorre's performance in M.

They first considered him to play the assassin in the film, but wanted to use him in a larger role despite his limited command of English at the time, which Lorre overcame by learning much of his part phonetically. Lorre soon settled in Hollywood, where he specialized in playing sinister foreigners, beginning with Mad Love (1935), directed by Karl Freund.

The Maltese Falcon (1941), his first film with Humphrey Bogart and Sydney Greenstreet, was followed by Casablanca (1942). Lorre and Greenstreet appeared in seven other films together.

Frequently typecast as a sinister foreigner, his later career was erratic. Lorre was the first actor to play a James Bond villain as Le Chiffre in a TV version of Casino Royale (1954).

Lorre starred in a series of Mr. Moto movies, a parallel to the better known Charlie Chan series, in which he played John P. Marquand's character, a Japanese detective and spy. Initially positive about the films, he soon grew frustrated with them. "The role is childish," he once asserted, and eventually tended to angrily dismiss the films entirely. He twisted his shoulder during a stunt in Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation (1939), the penultimate entry of the series.

Frustrated by broken promises from the Fox studio, Lorre had managed to end his contract. He went freelance for the next four years.

In 1940, Lorre appeared as the anonymous lead in the B-picture, Stranger on the Third Floor, reputedly the first ever film noir. The same year, he co-starred with horror actors Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff in the Kay Kyser movie, You'll Find Out.

In 1941, Lorre became a naturalized citizen of the United States. Writing in 1944, film critic Manny Farber described what he called Lorre's "double-take job," a characteristic dramatic flourish "where the actor's face changes rapidly from laughter, love or a security that he doesn't really feel to a face more sincerely menacing, fearful or deadpan."

Lorre had suffered for years from chronic gallbladder troubles, for which doctors had prescribed morphine. He became trapped between the constant pain and addiction to morphine to ease the problem. It was during the period of the Mr. Moto films that Lorre struggled with and overcame his addiction.

Having quickly gained 100 pounds and not fully recovering from his addiction to morphine, Lorre suffered personal and career disappointments in his later life.

He died at age 59 in 1964 of a stroke.

Here, Lorre plays Ugarte with Humphrey Bogart as Rick in the famous “Letters of Transit” scene in Casablanca, 1942

Col. Tom Parker and Elvis Presley

Colonel Tom Parker, manager of Elvis Presley, was born 114 years ago today.

Parker’s management of Presley defined the role of masterminding talent management, which involved every facet of the client's life and was seen as central to the success of Presley's career.

"The Colonel" displayed a ruthless devotion to his own financial gain at the expense of his client. While other managers took compensation in the range of 10 to 15 percent of earnings, Parker took as much as 50 percent toward the end of Presley's life. Presley said of Parker, "I don't think I'd have ever been very big if it wasn't for him. He's a very smart man."

As a boy, Parker worked as a barker at carnivals in the Netherlands where he was born, learning many of the skills that he would require in later life while working in the entertainment industry. At age 18, with enough money to sustain him for a short period, he entered America illegally by jumping ship from his employer's vessel. His trip was also motivated by his wanting to avoid criminal arrest on a murder case at home.

He enlisted in the United States Army, taking the name "Tom Parker" from the officer who interviewed him, to disguise the fact he was an illegal immigrant. Parker went AWOL and was charged with desertion. He was placed in solitary confinement, from which he emerged with a psychosis that led to two months in a mental hospital. He was discharged from the Army due to his mental condition.

In 1945, Parker became Eddy Arnold's full-time manager, signing a contract for 25 percent of the star's earnings. Over the next few years, he would help Arnold secure hit songs, television appearances and live tours.

In 1948, Parker received the rank of colonel in the Louisiana State Militia from Jimmie Davis, the governor of Louisiana and a former country singer, in return for work Parker did on Davis' election campaign. The rank was honorary since Louisiana had no organized militia, but Parker used the title throughout his life, becoming known simply as "the Colonel" to many acquaintances.

In early 1955, Parker became aware of a young singer named Elvis Presley. Presley had a singing style different from the current trend, and Parker was immediately interested in the future of this musical style. Elvis’ first manager was guitarist Scotty Moore, who was encouraged by Sun Records owner Sam Phillips to become his manager to protect Elvis from unscrupulous music promoters.

In November, 1954, Parker persuaded RCA to buy Presley out from Sun Records for $40,000, and on November 21 Presley's contract was officially transferred from Sun Records to RCA Victor. On March 26, 1956, Presley signed a contract with Parker that made him his exclusive representative.

With his first RCA Victor single, "Heartbreak Hotel" in 1956, Presley graduated from rumor to bona-fide recording star. Parker began 1956 with intentions of bringing his new star to the national stage. He arranged for Presley to appear on popular television shows such as The Milton Berle Show and The Ed Sullivan Show, securing fees that made him the highest paid star on television.

By the summer, Presley had become one of the most famous new faces of the year, causing excitement among the new teenage audience and outrage among some older audiences and religious groups.

On January 2, 1967, Parker renegotiated his managerial/agent contract with Presley, persuading him to increase Parker's share from 25 to 50 percent. When critics questioned this arrangement, Presley quipped "I could have signed with East Coast Entertainment where they take 70 percent!" Parker used the argument that Presley was his only client and he was thus earning only one fee.

In Elvis’s later life, Parker and Elvis grew apart and the singer would see very little of him. The two had become almost strangers to each other, and false reports in the media suggested that Presley's contract was up for sale.

Although Parker publicly denied these claims, he had been in talks with Peter Grant, manager of Led Zeppelin, about the possibility of him overseeing a European tour for Presley. As with all the talk about Presley touring overseas, Parker never followed through with the deal.

Presley fans have speculated that the reason Presley only once performed abroad, which would probably have been a highly lucrative proposition, may have been that Parker was worried that he would not have been able to acquire a U.S. passport and might even have been deported upon filing his application. In addition, applying for the citizenship required for a U.S. passport would probably have exposed his carefully concealed foreign birth.

Although Parker was a U.S. Army veteran and spouse of an American citizen, one of the basic tenets of U.S. immigration law is that absent some sort of amnesty program, there is no path to citizenship or even legal residency for those who entered the country illegally.

As Parker had not availed himself of the 1940 Alien Registration Act, and there was no amnesty program available to him afterwards, he was not eligible for U.S. citizenship through any means.

Throughout his entire career, Presley performed in only three venues outside the United States — all of them in Canada: Toronto, Ottawa and Vancouver, during brief tours there in 1957. However, at the time of these concerts, crossing the U.S.-Canada border did not require a passport. Parker, however, stayed in Washington and didn’t leave the country.

When Presley died in August, 1977, one day before he was due to go out on tour, some accounts suggest Parker acted as if nothing had happened. Asked by a journalist what he would do now, Parker responded, "Why, I'll just go right on managing him!"

Almost immediately, before even visiting Graceland, he made his way to New York to meet with merchandising associates and RCA executives, instructing them to prepare for a huge demand in Presley products. Shortly afterward, he traveled to Memphis for Presley's funeral. Mourners recall being surprised at his wearing a Hawaiian shirt and baseball cap, smoking his trademark cigar and purposely avoiding the casket.

At the funeral, he persuaded Presley's father to sign over control of Presley's career in death to him. Following Presley's death, Parker set up a licensing operation with Factors Etc. Inc., to control Presley merchandise and keep a steady income supporting his estate. It was later revealed that Presley owned 22 percent of the company, Parker owned 56 percent and the final 22 percent was made up of various business associates.

In a lifetime that saw him earn in excess of $100 million, Parker's estate was barely worth $1 million when he died. Parker made his last public appearances in 1994. By this point, he was a sick man who could barely leave his own house.

On January 20, 1997, Parker's wife heard a crashing sound from the living room, and when she heard no response to her calls, she went in to find him slumped over in his chair. He had suffered a stroke. Parker died the following morning in Las Vegas at the age of 87. His death certificate listed his country of birth as the Netherlands and his citizenship as American.

His funeral was held at the Hilton Hotel and was attended by friends and former associates, including Eddy Arnold and Sam Phillips. Priscilla. Elvis’s wife, attended to represent the Elvis Presley Estate and gave a eulogy that, to many in the room, summed up Parker perfectly.

"Elvis and the Colonel made history together, and the world is richer, better and far more interesting because of their collaboration,” she said. “And now I need to locate my wallet, because I noticed there was no ticket booth on the way in here, but I'm sure that the Colonel must have arranged for some toll on the way out.”

The Cyclone, the historic wooden roller coaster at Coney Island, opened on June 26, 1927 — 96 years ago today.

Despite original plans by the city to scrap the ride in the early 1970s, the roller coaster was refurbished in the 1974 off-season and reopened on July 3, 1975. Astroland Park has continued to invest millions over the years in the upkeep of the Cyclone.

The Cyclone was declared a New York City landmark on July 12, 1988, and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 26, 1991.

Jazz Cafe, Havanna